The first Lillian Warren paintings I saw were at the Pearl Fincher Museum, in Spring, Texas, in 2012. Those paintings were based on photographs she had taken from her moving car. The most interesting pictures in the show were of traffic jams, based on photos taken from behind Warren’s windshield. Interestingly, she only painted the cars. The backgrounds were white — neither the road nor the roadside nor the sky were depicted. It was as if the cars were floating in a indeterminate space. And what is a traffic jam? It’s you and thousands of other people stuck in a non-place; a place where you can not really do anything except wait. Where you came from and where you are going to are places. The trip between them is a non-place.

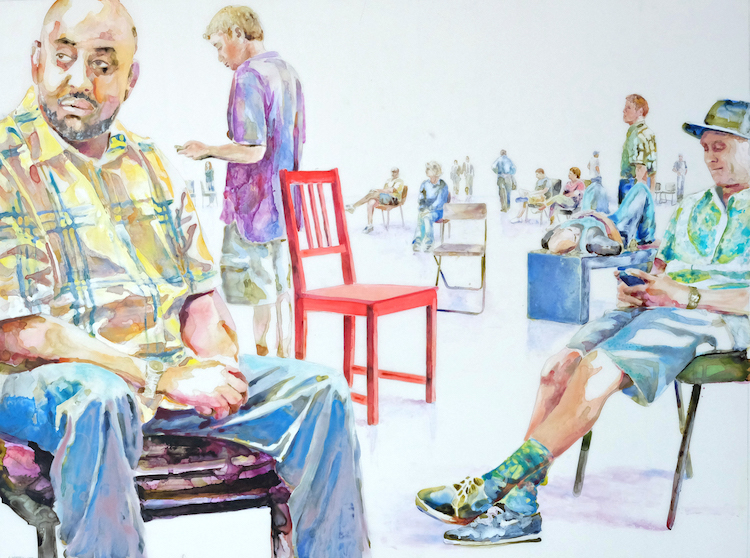

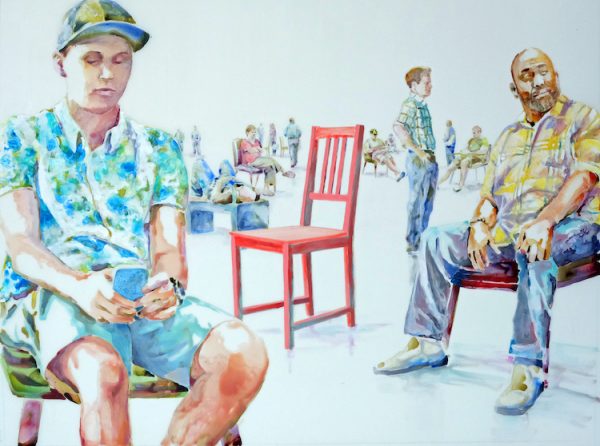

It was perhaps her interest in these non-places that lead to her series titled Waitscapes. These paintings of people waiting in white nondescript spaces are similar to the traffic photos, in that the location of the wait is a non-space. Think of an airport terminal or waiting at the DMV. Conceivably, one could spend one’s time in these purgatorial spaces chatting with other people who are also stuck waiting, but we usually don’t. We sit, maybe looking at our phones until we don’t have to wait anymore — the plane is boarding or our number is called. Warren will walk around such a place surreptitiously taking photographs, and she bases her paintings on these photos. The figures are highly rendered — realistic but painterly. There is no mistaking them for photographs; her technique of using watered-down acrylic on Mylar gives them the appearance of a watercolor. Because the Mylar surface is impermeable, and because she paints much of it with the Mylar flat on a table, we see places where the paint pooled up before drying. The process of painting the images is always visible, but the photographic origin is always detectable.

But one thing you notice as you look at these paintings is that Warren has taken multiple photos of the same people. For instance, Waitscape 110 (pictured at top) and Waitscape 111 both feature the same bald, bearded man in the yellow and blue shirt, viewed from different angles. In each painting, he is glancing off to the side. I read the two paintings as being in the same non-place at slightly different times. While nothing is happening — a group of people are waiting for something — time is passing. A narrative is therefore implied.

Paintings often work like that. Even if a painting is depicting a particular moment in time, there is often a narrative element because what happened before or after the event depicted in the painting is implied by the contents of the painting itself. This is not always true. A landscape or a portrait don’t necessarily have that sense of narrative. But when you consider paintings of mythological or historical or biblical events, there is always a narrative implied — one that’s often filled in by the knowledge or intuition of the viewers of the stories being depicted.

But even in realistic genre scenes, narrative is implied even if the specifics are obscure. One of my favorite paintings at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston is Interior by Albert André (circa 1893). This impressionist painting depicts a man and woman in a room with a bed. It could be a hotel room. The woman is standing in front of a mirror doing or undoing her hair, and the man is sitting at a table bent over as if tying his shoes. It could be either a pre- or post-coital scene. It could be a man’s assignation with a mistress or a prostitute, or a scene between a married couple. The story is that sex between the couple has happened or is just about to happen — the details of the assignation will be filled in by viewers’ imaginations.

But the narratives in Warren’s Waitscapes can’t be fleshed out that way by the viewer. The figures are blank slates. We don’t even know what they are waiting for, because Warren leaves them in a featureless space. The only story we can construct is that they are stuck waiting for something.

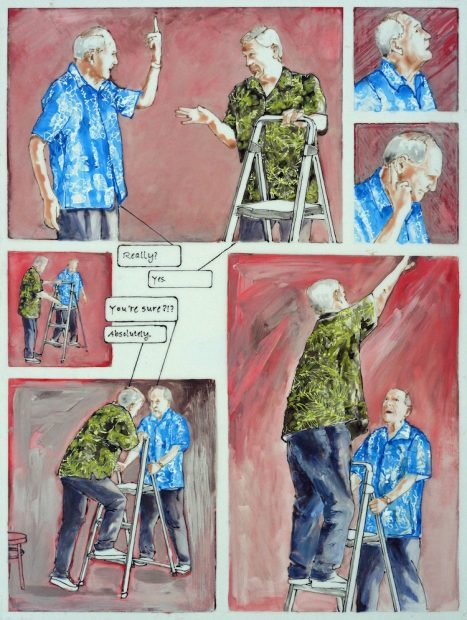

But Warren’s most recent works, currently on view at Anya Tish Gallery in Houston, make the narrative even more enigmatic. They’re based on photographs, but now Warren is posing her subjects. The figures occupy indistinct spaces, but they are doing things — interacting with other figures. Even interacting with themselves (because in these paintings, Warren will include the same figure more than once). In You’re Sure?, Warren has two figures (based on photographs of Houston art-world people Clint Willour and Reid Mitchell) having a discussion or argument about a stool. The Willour figure is depicted five times while Mitchell is shown four times. These multiple depictions at various distances in the imaginary blank space they inhabit suggests several distinct moments in time. We don’t know what the conversation is about, but the passage of time is clearly implied.

Dancing With the Elephant in the Room also features two figures depicted in multiple poses. The people who posed for these photos are also well-known in the Houston art scene — Nancy Wozny and Mari Omori. Omori is painted twice, making dramatic gestures (a big contrast to the mostly passive figures in the Waitscapes). But most curious is Nancy Wozny’s character. She is depicted three times, and one of the Woznys has her hands on one of the other Wozny’s shoulders. It’s impossible to construct a realistic narrative out of this image. There is an element of the fantastic in having one character’s doppelganger give herself a shoulder rub.

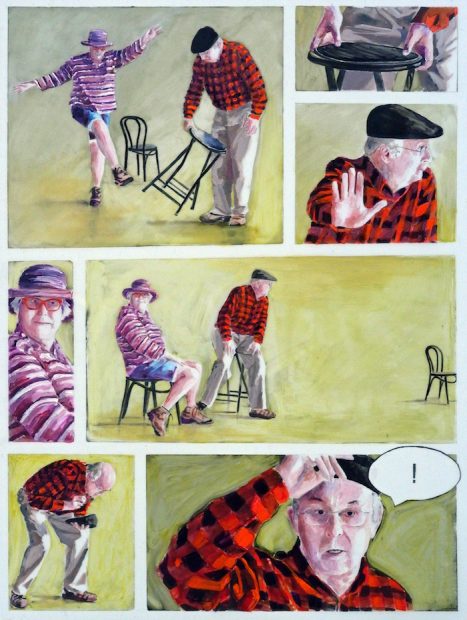

In 1993, Scott McCloud, in his book Understanding Comics, defined comics this way: “Juxtaposed pictorial and other images in a deliberate sequence, intended to convey information and/or produce an aesthetic response in the viewer.” This is relevant because in four of the works Warren shows here are clearly comics, employing techniques associated with comics — sequential images arranged on a page in rectangular panels, with clearly defined gutters separating the panels, with an action involving some characters. Not only do they fit McCloud’s definition of comics, but they look like comics.

McCloud was notoriously formalist — if a thing didn’t fit his definition, then it wasn’t comics. His example of a piece of non-comics that people often mistook for comics was the daily comic strip The Family Circus by Bil Keane. This comic was a single panel depicting the lovable adventures of Bil and Thelma and their four children Billy, Dolly, Jeffy, and P.J. Most people would call it a comic or a comic strip, which is where McCloud’s definition falls flat. In his attempt to build a formalist definition, he created one where things that seemed obviously to be comics (like The Family Circus) weren’t, while things that obviously had nothing to do with comics (say a series of unrelated paintings hung in a museum) would be comics. Part of his problem was “juxtaposition.” The idea was that you had to have more than one image. But if you’ve ever read The Family Circus, there is often a little story being told, with a beginning and end. Even without “juxtaposition,” Bil Keane managed to tell little stories.

In several of Warren’s new paintings, she does this. She layers different periods of time on top of one another to imply narrative. In her new narrative paintings, both the superimposed ones like You’re Sure? and Dancing With the Elephant in the Room, as well as the four comics pages (Well…?; I; Look…; and Really) feature sequential juxtaposed images, and there are two figures interacting in an indistinct space. Their interactions are oblique. Nothing really happens. The indistinct spaces they inhabit may remind one of experimental theater of a certain vintage. We the viewers must impose our own narrative onto the scenes. After years of depicting non-spaces and the nothingness that occurs in them, this seems like a big shift for Warren. Who knows — maybe the next step will be actual stories. She has certainly made a start in that direction. But perhaps she’ll do a hundred paintings of oblique, mysterious interactions before she tries to construct a traditional narrative.

On view at Anya Tish Gallery, Houston through June 23, 2018