We have thrown out the cry-baby in us.

Dadaist manifesto, 1918

We are always eating from the trash can of ideology.

Enda Deburka, 2017

I’m old enough to remember when the country was in a good mood. These days, whether facts on the ground wholly support it, it’s starting to feel like we are in as bad a situation as we have been in since the 1960s, if not the world wars. Like corpses unearthed in a New Orleans flood, the ills of society are freshly evident, ghastly and stinking. Your definition of what those ills actually are probably depends on your political leanings, but regardless, nobody right now appears calm. And the predominant response in the non-commercial art world of kunsthalles and biennials has been a torrent of “socially conscious” or “socially engaged” art.

I say non-commercial, because the commercial art market at the global level has become its own unfortunately exposed cadaver. Many of the objects that are haggled over in the marketplace barely qualify as art. They’re high-end décor — sometimes very good décor, let’s not knock it — and of course, indecently overpriced. The commercial art market is definitely not trying to save the world. It feels like something the world needs to be saved from.

Meanwhile, the other art world — the world of grants, residencies, kunsthalles and public art — is determined to save us from ourselves. Calls for residencies and public art increasingly ask artists to address specific issues like racism, misogyny, gentrification, the environment, immigration, or homelessness. Artists are expected to “develop their socially-engaged practice through volunteer opportunities” and “build and demonstrate models of a better society.” They are sometimes told specifically what non-art organizations they will be expected to work with. Woe to the introverted artist who prefers to work in relative solitude: that model is no longer fashionable or even socially acceptable.

The impetus for all of this is understandable, of course. Artists and curators see what is happening in the world. They want to help. They want to make a difference. But so much of the socially engaged art out there reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of art. A century after Duchamp, I think the art world has lost its sense of what art is, and more importantly, what art can and cannot do.

In a dark time, art is very good at pointing out the ills of society and articulating a collective sense of rage, anxiety or despair. William Pope.L, Karen Finley, and David Hammons, among many others, are masters of this, as were Goya and the Dadaists back in the day. Dada was a movement that emerged in the context of a war so catastrophic that it’s difficult for us to imagine. Their manifestos weren’t about addressing this or that nitty-gritty problem. They aimed to fundamentally change the way people saw the world, in order to change the world.

Of course, changing the way people see the world is not the same as trying to fix specific problems of society. Art can illustrate problems, but it can’t fix them, and a lot of this socially conscious art we’re seeing fails in part because it’s not art — it’s political activism, or anthropology, or charitable outreach. It may work beautifully as those things, and those things are certainly worthwhile, but they are something other than art. We’re paying the price for Duchamp, having to acknowledge these “artists” are making “art,” when their works would be better suited to political rallies, classrooms, science museums, or — sometimes — dimly lit hallways in suburban municipal planning buildings.

Visual art cannot fix the world because it’s not about that: it’s simply about seeing the world. And it isn’t legible. It communicates, but not as language. So when you try to make it legible and activist — when you try to spell things out and use art to solve things like flood control or gun violence — things go south in a hurry.

The resulting art is not only bad, it’s about as effective as a banana cream pie, as Vonnegut would say.* At its worst, socially conscious art is preachy, naive, visually dull and condescendingly pedantic. This makes going to see it feel like going to a particularly drab church and being lectured about your sins if you don’t relate to the message, or being preached at in the choir if you do relate to the message.

Which is not to say that art shouldn’t have a social consciousness, or that it’s even possible for it not to. In an interesting conversation on the British writer Matthew Collings’ Facebook page recently, the artist Enda Deburka commented that “there can be no art i.e. art production outside of society i e. social production.” Of course. All art is socially conscious, in the sense that it’s made by humans who are part of human society, responding to their experience of that society.

So how does socially conscious art transcend the trite? How does it avoid becoming a slave to its message?

For one thing, it can’t worry about the audience. William Pope.L and Karen Finley aren’t going to give you what you want or what you expect. Like Charles Barkley, they are not trying to be a role model. They’re fully committed, and they’re going to come out swinging heavy and hard, but with sophistication and discipline.

More than anything, great socially conscious art upsets the apple cart and stakes out new territory. It surprises you. Once Pope.L and Finley have done their thing, you can’t mimic them. If you try, it will be first-rate-second-rate pastiche. Unfortunately for all of us, kunsthalles and triennials rarely reward the unfamiliar. They want something the cognoscenti can agree upon as good.

Which leads me to Prospect.4, the latest installment in the New Orleans triennial of contemporary art.

Prospect has succeeded over the past decade because of its location in one of the most fascinating and distinctive cities in the world. In his essay for this year’s catalog, curator Trevor Schoonmaker shines when he describes his visits to New Orleans. The city itself, in all its contradictory richness and pleasure and dysfunction and chaos, is the best thing about Prospect.

But New Orleans has never been a visual art town. I think it’s because visual art can’t compete with the city itself, whereas its music interweaves with the spectacle, becoming an integral part of it. There is also no city in the United States more ready to encourage you in soft-edged, languid pleasure than New Orleans. It’s one thing to look at contemporary art in a rough building in Long Island City or the LA warehouse district; but in New Orleans, it’s hard not to feel like you’re missing out on the good stuff while you’re looking at yet another clever art installation.

Schoonmaker clearly loves New Orleans. He also understands the pitfalls of his profession. He has a warmth and expansiveness as a curator that’s refreshing. He avoids constipated art jargon and he’s good at communicating a sense of joy and hopefulness, particularly when he discusses music. Writing about the deaths of Prince and David Bowie last year, he says, “Moments such as these demonstrate the critical role played by artists… not only in rousing us, stimulating debate, and sharpening our focus on the work that must be done but also in inspiring us, reminding us of the wondrous beauty in the world, and proposing alternative visions for a better future.” Of course, what he doesn’t say is that both Prince and Bowie were controversial and unrecognizable when they got going. There was no ‘consensus’ on them. They were as Dada and disconcerting as anything that’s happened in music, image-wise, just completely throwing out convention. It was only later that everyone caught up with how great they were.

But as a curator, Schoonmaker doesn’t appear to be concerned with outwitting history. More than anything, he exhibits a warm generosity of sprit that seems to want to stay the course and keep things positive, writing “Art has the generative power to inspire, heal, and push both the spirit and society forward” and “Prospect.4 is a reminder that artistic activity in the form of resistance to injustice can be a path to healing.”

His enthusiasm and optimism are endearing, but as solid as some of the individual artworks in this Prospect are, I don’t think overall it moves the needle, either towards healing or towards change.

In everyone’s defense, an international art triennial is not the best venue for artists who really want to shake things up. Also, none of us are probably ready for healing just yet. We’ve barely processed police brutality or gay rights or the fact that Donald Trump is the President, to say nothing of the crappy way women are treated in the workplace. As for change, some of the works in this Prospect are too obvious and pat to do anything other than reinforce the preconceived notions of the cadre of international art-watchers who are their primary audience. The sugar industry has historically been terribly problematic: check. Monuments to bad people are bad: check. Muslims should be allowed to drink beer: absolutely.

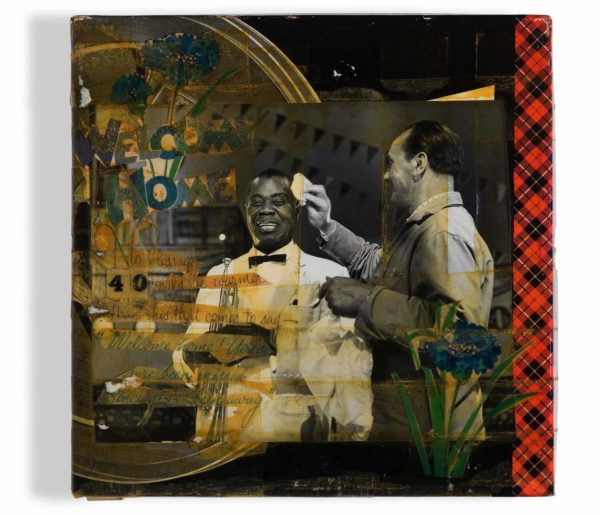

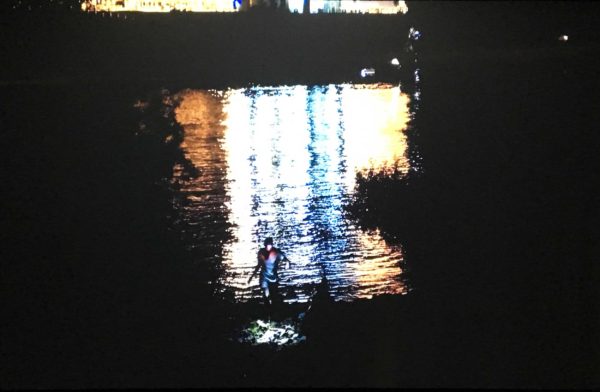

Prospect is spread out over the city in 17 different locations. This year there are roughly 80 artists participating. I wasn’t able to see everything, but I saw a lot of it. I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention certain standouts, like Darryl Montana‘s astounding costumes for the Black masking Indians of Mardi Gras; or the photographer Genevieve Gaignard’s poignant, fusty-chic installation at the Ace Hotel; or Jeff Whetstone’s luscious, meditative video of Vietnamese fishermen along the Mississippi River, at UNO’s St. Claude gallery; or Jon-Sesrie Goff’s video of the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, highlighted by Sweet Honey in the Rock’s cover of the Sonia Sanchez poem “Stay on the Battlefield,” with its powerful refrain, “Come to this battlefield called life.” I liked Rina Banerjee’s janky mixed-media voodoo-ish figure and Quintron and Miss Pussycat’s jumble of cartoonish, vaguely sinister ceramic toys and sewn puppets. Finally, don’t miss Louis Armstrong’s remarkable collages from the 1940s and 50s/60s, which are on view at the Mint Museum. If jazz music could be seen, these are what it might look like: witty, riffing, and a little risqué.

More than any other, the piece that has really stuck with me is Zina Saro-Wiwa’s TABLE MANNERS. Like all good ideas, TABLE MANNERS is deceptively simple: it’s a series of straightforward videos of people eating. The installation at Prospect, on the top floor of the Contemporary Arts Center, includes four monitors playing two different videos each. The monitors are set up with a small bench in front of them, so that the viewer could theoretically sit “across” from the person in the video while they share a meal.

Each video begins with a shot of the full plate, and ends with its eaten remains. They are titled the first name of the person eating and the dish they’re consuming, i.e. Lewa Eats Roasted Corn and Pear. The people in this series of videos are all Africans eating silently with their hands. They stare calmly into the camera, and their implacable expressions could be interpreted anywhere from confrontational to assured to bored. The explicitness of their identities (they are all clearly African, wearing African clothes, eating African food with their hands) is unmistakably exotic for a Western viewer, even in New Orleans, the most African of American cities. But their activity is fundamentally, viscerally familiar. We all eat, and watching another human eat stirs a primordial recognition.

If one aspect of healing is to make us all feel a part of a larger humanity, then Sara-Wiwa’s videos achieve that, in the same way the clever, simple videos of the early Sesame Street years did. These interesting people, they say, are just like you. This is not to say the videos are art: they’re too close to straight-up documentary anthropology for that. They also don’t stir the same intensity of emotion as William Pope.L’s gigantic, shredded American flag or Kara Walker’s silhouettes of horror. But they work. They stay with you.

If you go to Prospect.4, see the shows, but be sure to make time for the city of New Orleans and its pleasures, however sanitized they may be post-Katrina. And if you don’t go, keep your ear to the ground. The next great work of art, the one that will change the way we see the world, is coming. It’s out there.

* “Fiction is harmless. Fiction is so much hot air. The Vietnam war has proved this. Virtually every American fiction writer was against our participation in that civil war. We all raised hell about the war for years and years—with novels and poems and plays and short stories. We dropped on our complacent society the literary equivalent of a hydrogen bomb. I will now report to you the power of such a bomb. It has the explosive force of a very large banana-cream pie—a pie two meters in diameter, twenty centimeters thick, and dropped from a height of ten meters or more.”

– Kurt Vonnegut, Address to P.E.N. Conference in Stockholm, 1973, as published in Wampeters, Foma & Granfalloons (1974).

4 comments

Thanks Rainey. I winced when I realized I missed my chance to see Prospect 4 at Thanksgiving, but you are right, it’s hard to separate that ache from a pure nostalgia for the city. Good call, and I said the same things about activism in art as I walked out of a show last night, but it’s a little futile in private conversation, and I’m glad you’re saying it in print. I also wonder if art doesn’t become more social when underfunded; when it’s forced to multi-task in the competition for meager means, like an annoying entrepreneur making random comments about their business to make the meal you’re sharing deductible. It’s not easy to admit when art has gone sideways, but it’s great when criticism steers us back on course.

PROSPECT.4: THE LOTUS IN SPITE OF THE SWAMP

NOVEMBER 18, 2017 – FEBRUARY 25, 2018. You still have time to see it. I’m going in February with my wife.

You’ve said what I would have said and, as well written as I would have, were I a writer and, English my mother tongue. Art cannot save the world, yes art can change the way we see it, increase our understanding of it but, of course, it stops there and what the viewer does with that is another story. If an artist wants to be socially engage just be, go out create or join an organization that helps, really helps the cause of your choice, then make art. And then, yes, be that silent artist bringing forth the fruits of your creativity with full sincerety. Making art is no different than being yourself. Unfortunately this might not give you kudos of approval from the art world and of course without it no money. This reminds me of what an artist told me once, “if it is money what you want, art is not the profession”. So it goes if it is social changes, equality, alleviate suffering…what you want , Art is not the profession.

I think I get where you’re coming from, however, the first step to solving or fixing a problem is identifying it. Which I believe you’ve done with the craftsmanship of this critique. Art identifies problems all the time, thus helping to solve issues, or at least take a step closer to the resolution. I also don’t understand how art is a form of a communication but not a language? Or how you can determine what’s art and not art and mention the Dadaist? I think it’s way too easy to be cynical nowadays because we’re all realizing how ugly the truth is as it reveals itself in this continuos unfiltered dialogue we call the internet. I’ll end with this, the funny thing about “problems” is how ironic they are, they give us purpose, they give us something to solve. I’m assuming, this concept is the very reason you wrote this article in the first place because you found something problematic and you felt compelled to start a conversation about it. (All this spawning from experiences you had with artwork)