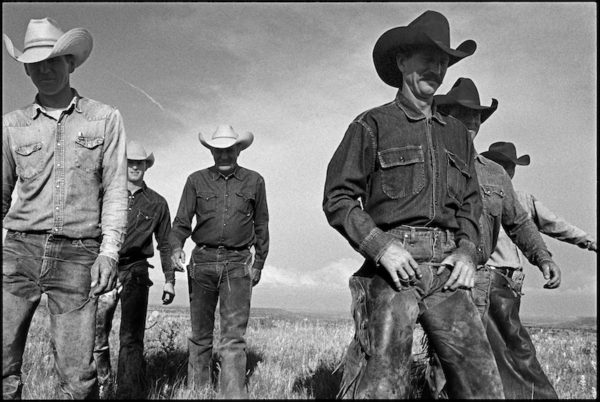

Cowboys Walking, J.R. Green Cattle Company, Shackelford County, Texas, May 13, 1997. Gelatin silver print.

The American Indian architecture of Jimmie Dale Gilmore’s cheekbones is definitely a thing. I had the opportunity to observe the indigenous features of his visage over a several-year period in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, when he often provided live pre-show music for a long-running play in which I performed entitled in the West.

As many times as I’d seen Jimmie Dale, I’d never seen that native, 19th-century, Crazy Horse’s-cousin look conveyed as strikingly as it was when I beheld it in an enlarged photograph in Laura Wilson’s exhibition That Day: Pictures in the American West at the Briscoe Western Art Museum in San Antonio.

The high-lonesome flatland singer shares wall space with Wilson’s images of fellow artists, including Sam Shepard, Donald Judd, Ed Ruscha, Bruce Nauman, Annie Proulx, and Harry Dean Stanton. Other groups rounded up for this expansive demographic rodeo of a show include cowboys and ranching folks, small-town six-man-team football players, fighter pilots, contemporary Oglala Sioux, and the Hutterite religious community of Montana. Mexican border images range from the struggling residents of Rio Grande colonias to Colonial Pageant debutantes decked out in $30,000 gowns for the annual Washington’s Birthday celebration in Laredo, one of the border’s traditional and quirkier expressions of regional surrealism.

The title That Day underscores the viewer’s sense of being there beside the photographer and the way in which the captured moment remains ever fresh in the image, some of which were made as early as 1979. That was the year when Dallas-based Wilson began assisting Richard Avedon with his own six-year photography project, In The American West. Describing Avedon’s portraiture process in her 2004 book, Avedon At Work In The American West, Wilson noted that he would wait for what Eudora Welty called “a story teller’s truth… the moment in which people reveal themselves. You have to be ready, in yourself; you have to know the moment when you see it.”

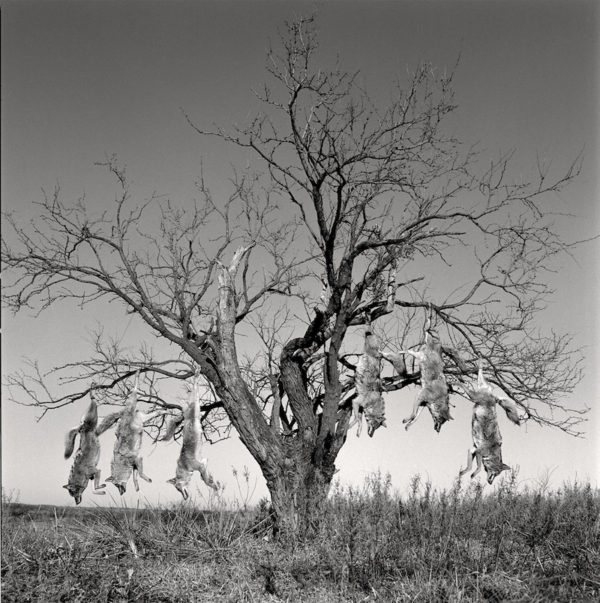

Much of the art world responded somewhat negatively to Avedon’s austere images of hard-squinting drifters, vacant mental patients, outsiders beaten down by barren landscapes, by life, by loss. He stripped away the glossy mythology of the west. The cowboy la-la-land of “Marlboro Country,” the writer John Graves once told Wilson, “is always just a little west of where you are.” The romance is in the setting sun. You prob’ly ain’t never gonna get there, but the road west is what it’s all about.

Wilson travels much of the same road in That Day but broadens its scope. While Avedon crystallized the humanity of those living in the margins of the west, Wilson supplements that documentary oeuvre while adding subjects whose storyteller’s truth has at least equipped them to better deal with dysfunction in a material sense.

Harry Dean Stanton, Set of Wendell Baker Story, Circleville, Texas, September 22, 2003. Gelatin silver print.

The late actor Harry Dean Stanton might serve as a figurative bridge between the two worlds. Wilson’s photograph of him, seated with guitar in front of a Beechcraft Model 18 airplane on a film shoot in Circleville, Texas, hints at the expression of one who could have been plucked from the vastness of the west — perhaps as he trekked through the desert in Wim Wenders’ film Paris, Texas — to stand wounded and dangerous before Avedon’s blank background canvas.

The grizzled, one-eyed, roadmap face of the late writer Jim Harrison also contains multiple universes. While consuming prodigious quantities of cigarettes and liquor during their afternoon shoot in Patagonia, Arizona — a habit that Wilson confesses alarmed (and surely intrigued) her — Harrison quoted W. H. Auden and wore bedroom slippers as they walked along a creek for outdoor image making.

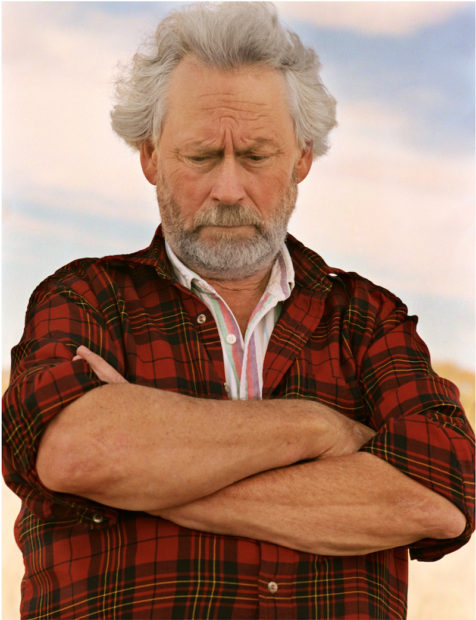

Equally rough-edged and refined was Donald Judd, whom Wilson photographed in Marfa in early November, 1993, before the artist was diagnosed with the cancer that took his life less than three months later. “I found Judd to be suspicious of me, which made him difficult to photograph, and ornery, which made me like him,” the photographer writes in the sumptuous, large-format That Day catalog, published by Yale University Press.

She photographed Judd for a piece in London’s Sunday Times. Body-language voodoo readers would have a party with her portrait of him, with his tightly folded arms and stern, downward gaze. One wonders how much billy-goat-gruffer the artist would have been had he known that the British newspaper editor described him as a “minimalist maverick.” But in the overall context of That Day, the art grouch was kind of a pussycat.

In an online interview, Wilson noted, “Many of the things that interest me are difficult to get access to.” It’s remarkable how many obscure and hidden-niche cultures of the west she was allowed to photograph. Some were even zones of illegal activity. The cock-fighting images from Cotulla and the Webb County dog-fighting images are difficult to look at, but they are, sadly, still a part of the American West.

Obviously, she gained valued experience in approaching and requesting to photograph figures from the western heartland’s big bucket of strange while working with Avedon, but the verve and finesse she exhibited in winning over the Hutterites is another story. A self-contained scattering of religious farm colonies on the northern Great Plains, they strictly shun the modern world and all its geegaws.

“Photography,” Wilson writes, “is against Hutterite beliefs. To have one’s picture taken is considered a worldly distraction, a direct contradiction of God’s commandment that forbids vainglory.” On her first three visits with Montana Hutterites, beginning in 1985, she did not even bring a camera. Over time, they began to trust her and to understand that she did not intend to sensationalize their way of life. And eventually, they relented, resulting in Wilson’s 2000 book, Hutterites of Montana and the selections in That Day.

“With my keen conscience,” one Hutterite woman told Wilson, “I’ve been thinking and thinking about what you’ve been doing, and if it’s wrong that you’re taking pictures. I’ve come to the conclusion that maybe a soul can be saved by reading your book and looking at the pictures — the way we dress, our modesty, the kind of life we lead… . That would gratify God.”

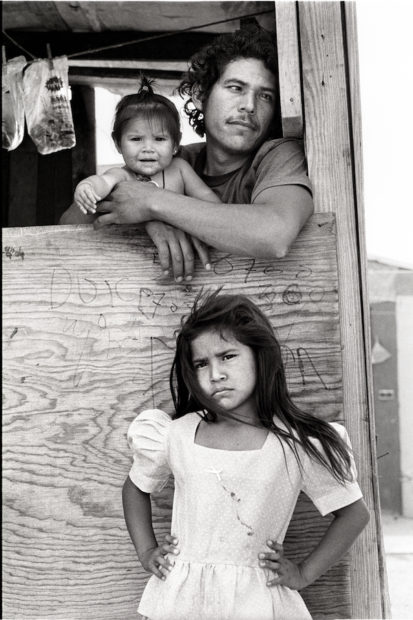

Sensitively deployed interpersonal skills were likewise required to navigate access and permission to photograph impoverished residents of Nuevo Laredo colonias in 1993. The powerful image Blind Woman and Child echoes Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother of 1936. We are also drawn into Wilson’s Child with Father and Sister, in which a young girl, hands defiant on her hips, her face creased with wisdom beyond her years, won through the angry crucible of longing and hardship, looks into the camera. “You’re going soon,” one can almost hear her say, “back across the river to America and your life of luxury and ease. And we’ll be here, where we have nothing. We’ll be here.”

“When I look at an old photograph, particularly [that] one,” Wilson writes in That Day, “I often wonder what’s become of the person in the picture.” One cannot help but wonder.

As she indicates in an interview, the human face is the image that compels Laura Wilson to make photographs. Though she denies being a landscape photographer, she does not deny her subjects their inhabited territory, as Avedon did, and several exhibition images reveal a world not focused on the human form. One of my favorites is the compelling, mostly deserted Hacienda de San Diego, one of the largest prints in the Briscoe show. The ruin in the Mexican state of Chihuahua was built in the late 1860s by Luis Terrazas, the governor of Chihuahua and cattle tycoonisto whose ranchos reportedly covered more than seven million acres. But years before his death in 1923, Wilson writes in That Day, Terrazas himself was ruined, his empire gone with the dust from Pancho Villa’s horses sweeping across the desert.

John Rohrbach, senior photography curator at Fort Worth’s Amon Carter Museum of American Art, where That Day debuted, notes that in addition to revealing the great range of cultures in the modern west, Wilson also maintains a traditional, romantic view of the region. The photographer herself merrily reveals that all the kids in her northeastern childhood were “obsessed with cowboys and Indians.”

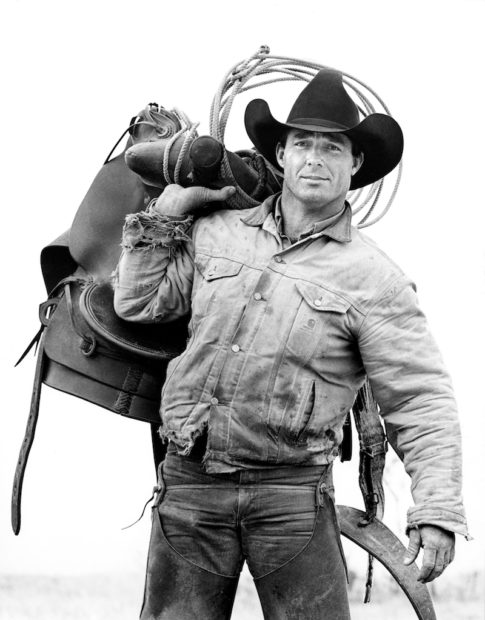

Donny Baize, Cowboy, J.R. Green Cattle Company, Shackelford County, Texas, March 18, 1997. Gelatin silver print.

I’m a sucker for authentic cowboy iconography — in my own perhaps twisted perspective it’s a peppy nook of the American avant-garde — and thus many of the boots-hats-and-saddles images are among my favorites. And look at these guys. Look at the get-‘er-done, self-reliant hombres in Cowboys Walking and Donny Baize, Cowboy. And the female rodeo athletes of Trick Riders. How can the modern world be so screwed up while these figures still walk the earth?

The photographer who captured those folks understands the storyteller’s truth of Tresa Valentine, litter-gitter driver with the highway department. Tresa was Jo Carol Pierce’s character in our play in the West, which sought to present a softer and more nuanced edge of the region than that depicted in Avedon’s images — or at least a version of its crazy-cray in a greater variety of socio-economic strata.

When Avedon wanted to photograph Tresa, she thought there must be something wrong with his eyes. He could have, for instance, instead photographed Katie Crawford, the town’s Maid of Cotton. So Tresa went to the museum to see his exhibition and find out what must be haywire with the photographer’s vision.

“O. K. The first thing is,” she told him as she prepared to pose in front of a blank background, “we’re not standing all alone out here like the people in your pictures. If you took a real picture of me, there’d be literally hundreds of people in it. But those people in your pictures look like nobody knows them. People where you come from look like that, the few I’ve seen. So one thing you could do is change your title from ‘In The American West’ to ‘People in the East dressed up to look like people in the West.’

“Another thing that’s not showing up is how… this is hard to put into words — I didn’t really think you’d want to hear it… well… there’s nothing here. And there’s nothing in your pictures. But your nothing is right at your back. Just look out on that highway and tell me where our nothing stops. Our nothing goes on forever, doesn’t it?”

Through Dec. 10, 2017 at the Briscoe Western Art Museum, San Antonio.

1 comment

This is not an exhibit I would have gone out of my way to see – until I read your article. Thanks for describing it so richly, I feel like jumping in my car and driving to SanAntonio and waiting for the the doors to open.