Adam Fung’s Iceberg X at Ro2 in Dallas, a series of paintings based on photos and video taken during a unique residency in the Arctic Circle, brings together and fetishizes science, nature, and activism. Fung’s project during this 2016 residency, a three-channel video shot using aerial drones and submersible cameras, is also on display in the gallery. The video tries to get in and under, around and above the ice — to see it and record it in new and more immersive ways. The paintings, on the other hand, try to make deeper sense of the experience, and of the memory recorded in those flat objects.

The dozen or so small and medium sized works are all done on linen. Either painted in monochromatic hues of oil, or with graphite and conté, they’re cool and beautiful on a white wall. Their narrow color spectrum plays up the ghostly imagery — part Robyn O’Neil’s apocalyptic landscapes, part Vija Celmins’ disciplined renderings.

The largest work here, iceberg quinacridone X, is a deathly still portrait of a vascular and stratified chunk of ice floating above its glassy reflection. It’s the most personified and mournful character in the cast. It has a symmetry straddling the horizon that rhymes visually with ‘X.’ Clusters of icy slush float below, clouds above, everything made of water, everything echoing itself in forms.

In his statement, Fung explains the X not as a semiotic motif, but as longitude lines crossing at the pole, the place where map-space warps around on itself, the edge of the flat world. But these X’s over the surface are doing the obvious: taking away. The content of the works in this sense are bumper-sticker-level direct. And there’s an eco-romanticism that you must get past to enjoy the work.

The careful way the X is woven into the fabric of the picture is of more interest to me. I sense in it a planned-out, contemplative process that tries to physically stretch a symbol over a memory, to work it in, to calculate loss. I can see this being a cathartic grieving act, or a means to ground an emotion in a physical activity. The content of painting is at one level the act of painting itself, which contains the thinking space between a body and the specter it’s caressing into being.

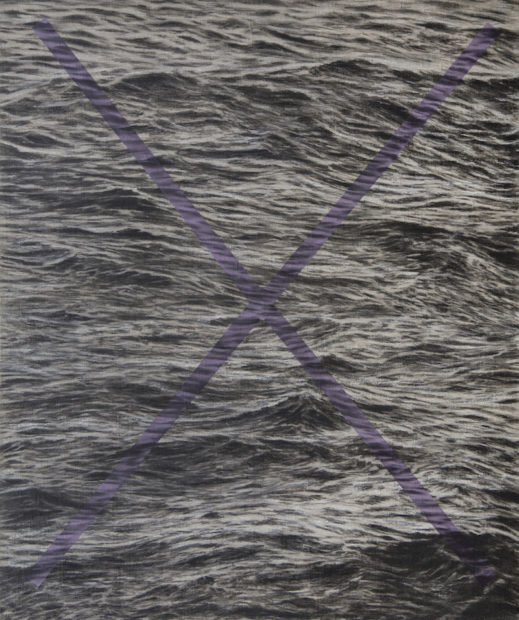

Arctic sea provence violet X frames in the pattern of peaks and valleys in a foamy sea, filling the entire composition, with the black-and-white sea done in graphite and conté, the “X” done in oil, and appearing to filter the information behind it through the paint.

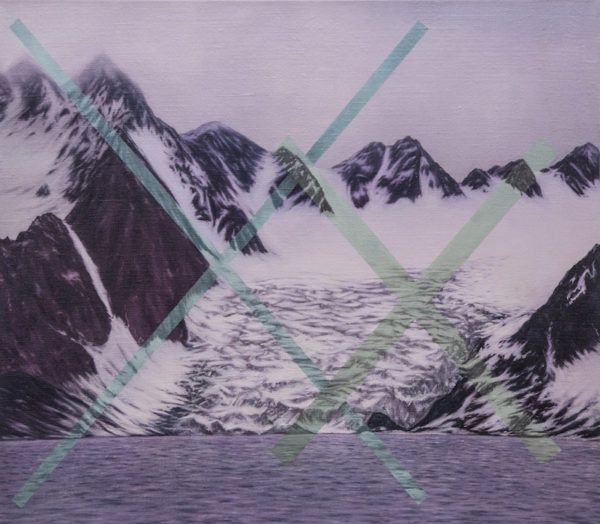

Another with this all-over composition is glacier green pthalo blue xxX. The marks here are looser and thinner, letting the linen peek through and breathe.

What I like about Fung’s older work is what I also like about this group: They are meticulous and confident. They try to invoke the infinite without taking up a lot of space themselves. His work has been consistently about nature and geometry, and is carried out in a careful, meditative hand. Small work — non-objective, pattern-based, as well as naturalistic — looks for scale relationships that dwarf you in the abstract while easily fitting in your microwave. This series follows along those lines.

Worth noting: There’s another way of interpreting the presence of Fung’s X. Arctic mountains gold X gives the X depth and shadows in the space and light of the picture. Technologically augmented ways of seeing are baked into them. They may be executable without the software processing they reference, but they would not be “get”-able without it already being part of our visual language. This kind of effect is commonplace in all kinds of media now, but I remember seeing versions of it first in Schoolhouse Rock, then later in Wayne White’s word paintings. It seems harmless and playful, but opening up an image enough to swallow another type of space — the ether of the screen — changes the nature of images at a cellular level.

Even in these handmade paintings, the invisible lens of the camera invades the space of the image. It’s not what the X says that we should understand, but how our vision is constructed technologically. This is what actually separates us from nature; it’s our own understanding of nature, our picturing of it, our aestheticizing it. Our constant attempts to get closer, see clearer, see farther, to visually record and penetrate all things — in the end it only adds more and more mechanical processes between us and our experience of the world. And these technologies, though invisible, are commodifiable and driven by the same logic that will eventually snuff everything out.

For Fung, X marks the Arctic as a kind of center, rather than a corner or an edge. Ironically absent of humanity, yet eliciting the most powerful human responses, it’s a full-fledged encounter with the sublime other. Though aiming to erase old distinctions and forge a new relationship with nature, his work is full of the contradictions of nature + technology.

Part of me cynically questions the ability of pictorial regimes to stir our morality and affect any intended change. Every Christmas movie ever made warns against the commercializing of the holiday, and yet is a necessary part of that larger commercial package. It helps us cope, it absolves us, all the while working to keep the gears turning and the warehouses teeming. Campaigns that bring awareness to us about the vanishing earth educate and humanize its far-away corners. The arctic would no doubt be better off if we never knew about it in the first place. But here we are.

We obviously love the ice, we want to save the ice. Most of us trust those more knowledgeable that it’s really important, and even though we can’t all float around and enjoy its otherworldly beauty, we’re glad some brave souls do, and bring us back the pictures. My question is this: How does that approach work in the long term to save the things we make into beautiful poster children? How is the aestheticizing of nature-as-other linked to the well-being of said nature? I’m fearful that after our late attempts to stop the wheels of our own civilization from crushing everything it sees and loves, we’ll be left with nothing to do but sing a sad song, and paint a sad picture, that at least consoles us that we were on the right side.

Through Oct. 28 at Ro2 Art, Dallas.