Polaroid effectively shut down in 2008, right in the middle of a nostalgia wave that shows no signs of slowing. The affection and recognition of Polaroid as a phenomenon has gripped generations of amateur and professional photographers, and still does to a degree, and the current show at the Amon Carter is a loving homage to a form, but it’s also a funereal afterword, and maybe also the denial phase of grief — this one authored by the artists who’ve embraced and stretched the technology over the decades. It’s a beautiful show, and a poetic and expansive illustration of a form’s life and death. It’s years in the making and it opens not a moment too soon. Nostalgia or no, our technology revolution means that time is speeding up the way we look at and make everything, and even earnest efforts like the Impossible Project can’t put that ferocious and very hungry cat back in the bag.

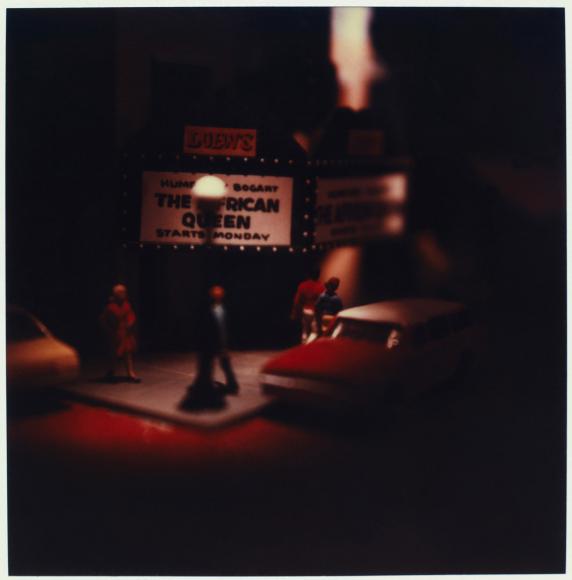

But in its heyday Polaroid presented a marvelous example of a seemingly limited but still plastic technology, just the type that artists love to take on. Polaroid’s various Artist Support programs put its cameras and film into the hands of some of our best-known artists. Images by Ansel Adams, Walker Evans, Andy Warhol, Chuck Close, Robert Mapplethorpe, David Levinthal, David Hockney… art lovers immediately recognize these artists’ Polaroid work, and as a company Polaroid built a massive and famous collection of art photography. Much of what’s on show at the Amon Carter comes from the collection (which has been split apart by auctions and other sales during and following the company’s bankruptcy), but the curators also spent years reaching out to artists and their representatives to see what else was out there, what they may have missed.

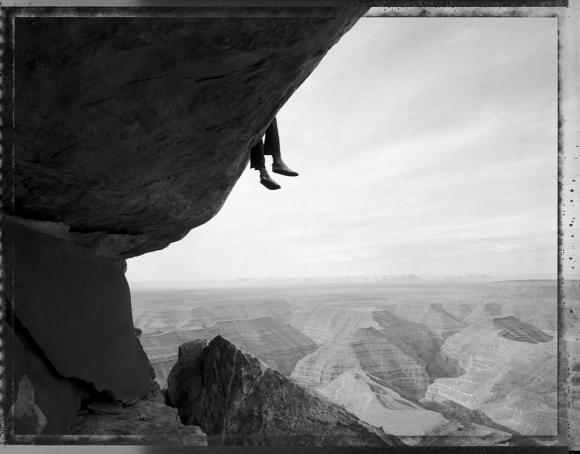

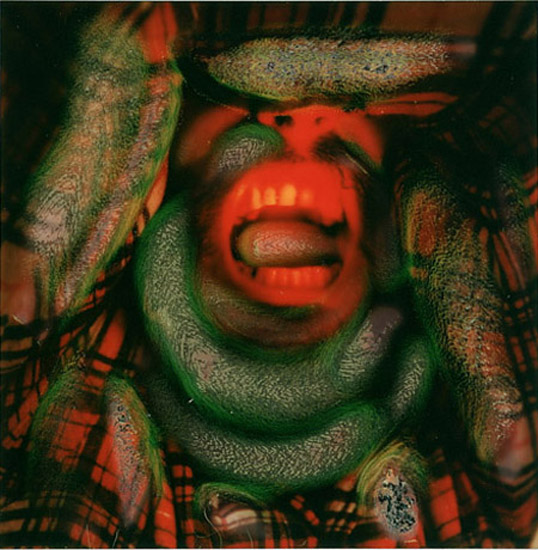

This is the first stop for what will be an international traveling show, and it’s only one iteration of it. But the Amon Carter, given its deep relationship with photography, is of course a most doting host — the installation is dramatic and satisfying. If there was a golden age of Polaroid art photography (and especially experimentation), I’d put it between the late 1960s and mid-‘80s, but the show includes examples of much older and newer work than that as well. And it’s fascinating to take in the staggering range of how artists used Polaroid. One the one hand you have the inarguable (and frankly surprising) formal beauty of a black-and-white landscape photograph by Mark Klett — it looks like it must have been taken by the most sophisticated (non-Polaroid) film and lens combo out there — and on the other you’ve got Lucas Samaras’ mind-bending hallucinations that could only have sprung from the weird parameters inherent to Polaroid. The show is one of the best testaments I’ve seen to artists’ intellectual curiosity and need to challenge convention, and all the while feeding their own impulse to make beautiful and compelling things.

It’s impossible to walk through the show and not start thinking about what technologies we’re dealing with now that will be ushered out in the next few years to make room for the new. In 1970 Polaroid’s visionary founder, Edwin Land, essentially predicted the smartphone camera.

“The camera that would be oh, like the telephone, something that you use all day long. Whenever an occasion arises in which… you cannot trust your memory… A camera that you would use as often as your pencil or your eyeglasses. [Land pulls his wallet out of his pocket and opens it.] Like being able to take a wallet out of my pocket, and perhaps open the wallet, press a button, close the wallet and have the picture.”

My understanding is that he also predicted you’d be able to share these images instantly, as widely as you wanted. What he may not have predicted was that in 2017, most people, including artists, embrace and use their smartphones every day, but are still pining for Polaroid.

Through Sept. 3 at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth.