What does Orange, Texas conjure in the mind? It’s one of those quaintly named Texas towns that could also be the name of a regional Lake Wobegon-like show staged at a newly built performing arts center in a wealthy suburb of North Dallas. For me it is the first place you can get good boudin and crackling on the drive to New Orleans. Texas could easily be four separate states (or five?) — West Texas is the third Southwestern state, North Texas belongs to the plains, South Texas is a unique hybrid of several cultures (German, Mexican, etc…), and east Texas is the Deep South: lush, watery, and menacing. Somewhere past Houston you begin to enter True Detective Season One world. The luminescent cactus cities of refineries light the way, the air becomes rich with brine and oil, and eventually gas stations start advertising various wild animals they have on display for your amusement.

Orange, Texas was once the lumber center of Texas and the Stark family the richest barons. The Starks accumulated a refined and impressive collection of Western American Art, and after W.H. Stark’s death and bequest of the family collection, the Stark Museum opened in 1974. This is why the sleepy bayou town of Orange is home to perhaps the best Western Art Museum in the country, and the reason I traveled there with my dad to see its current dazzling show Branding the American West.

At the otherwise generic Best Western hotel the sense that we were in a different part of Texas was apparent as two middle-aged men in Ed Hardy jeans murdered an eighteen pack of Heineken and scream-laughed a stream of excited Creole (?) by the pool. I decided that all restaurants and bars we visited should be on the bayou so we ate serviceable gumbo at Peggy’s on the Bayou as the sun set and the light in the clouds denoted Christian sympathy cards. We grabbed a beer at the Bayou Club, a shack really, an instantly obvious classic bar — the drinks strong, the pool free, the patrons gently bombed and friendly. The bar had a sinking deck on the bayou and as I leaned on the rail and drank my beer and admired the twilight reflection on the water, a gator roared up causing me to cackle in fear euphoria. Later, an older woman regaled us with stories of working on a gator farm as she splashed beer on the bayou gator’s head and laughed. In the middle of the night, the sky cracked with thunder in that especially loud Texas boom that suggests something important might happen (the rapture or the appearance of a nude time traveler — same thing I know). Near dawn, a rapping noise woke me up. The ceiling had split from torrential rain and water was dripping into our room.

Western Art is rightfully associated with the decoration in a private lodge where billionaire donors meet and decide Social Security should be converted into the McDonald’s Monopoly scratch-off game. A brooding luxury kitsch a certain type of American Oligarch collects — gazing at a painting of glorious nature hanging above his roaring fire, as he contemplates clear-cutting a forest or blowing the cap off a mountain for the minerals inside.

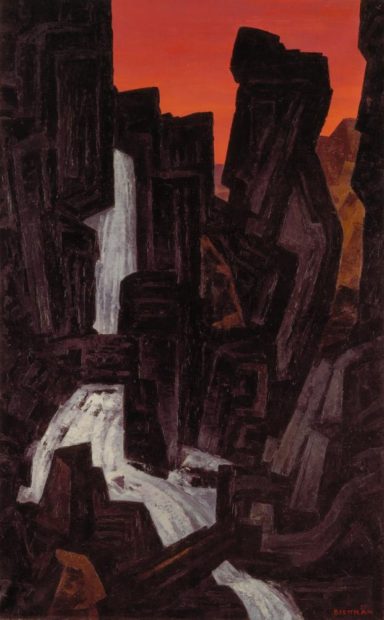

Therefore, I was expecting kitsch; a curiosity in a swamp town. And the stately limestone-block museum does hold some of that — especially with the porcelain birds by Edward Marshall Boehm and the Steuben Glass collection of crystal urns for each state in America (for the state’s ashes I guess). But the expansive and enthralling current exhibition, Branding the American West: Paintings and Films from 1900-1950, is remarkably kitsch-free, instead imbued with a dignified and melancholic gravitas. Framing the exhibit as “Branding” is a clever move. The media representation of the American west was certainly crafted to feed an insatiable appetite by much of the world for a gauzy romantic dream of blood and vistas. Because the scenery of the West is truly myth-making, branding the West was often accomplished by simply removing the people — and thus the brutality and struggle — or positioning them from a distance on horseback. Thus many of the paintings in the show are stately landscapes, often capturing the high-watt light of the American west with the same alchemy J.M.W. Turner conjured when painting the light off the water in Europe.

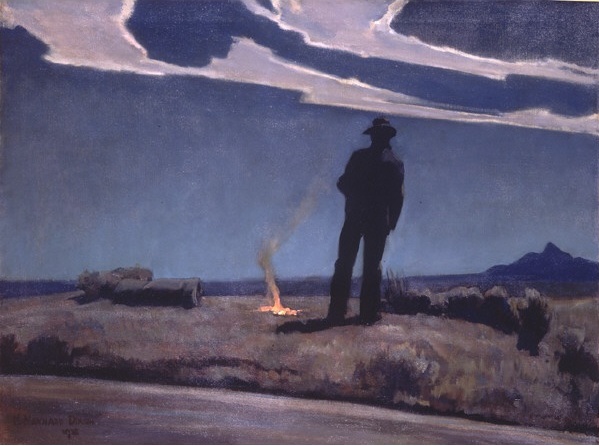

Frederic Remington, He Shouted His Harsh Pathos at a Wild and Lonely Wind, but There Was No Response, c. 1900, oil on canvas

There are of course several paintings of Native Americans in the exhibition, and most have a reverent sadness to them that sometimes veers into an exoticized hagiography. The best, such as Frederic Remington’s highly emo He Shouted His Harsh Pathos at a Wild and Lonely Wind, But There Was No Response (opening on tour for The World is A Beautiful Place and I’m Not Afraid to Die) depicts a Cheyenne chief on a frozen mountain, symbolizing like many of these painting an “end of an era.” And it feels confessional, a lament. After all, Native Americans were extremely hygienic and were apparently repulsed when first encountering Europeans who undoubtedly fogged their paths with rank BO. Native Americans were far superior horse-riders and navigators, and one can sense the unsettling of the foundation in white supremacy and manifest destiny — the realization that perhaps such a conquest was not ordained by God but simply a generational act of relentlessly cruel resolve.

The exhibition highlights several less famous Western painters, most strikingly Maynard Dixon. The star of the show (both in terms of number of paintings on display and range of subjects and general mastery), Dixon’s works span from gorgeous landscapes to a remarkable series depicting the Great Depression in the west. My favorite, Roadside, depicts a hobo by a wispy fire in front of an open sky. At once beautiful and deeply lonely, Dixon captures the dreamy desolation of being desperate in a staggering landscape.

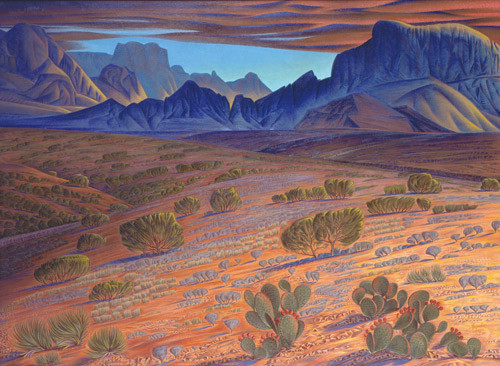

Equally as resonant as Branding the American West is the museum’s general permanent collection. The Starks had an eye for atmosphere as seen in expanses of Big Bend and emerald pools in Yellowstone. These convey an almost religious mysticism to the expanse beyond the humid forests where the family made its fortune.

The contrast between the setting of Orange and the contents of the museum provide an interesting ballast to the Chinati foundation at the other end of the state in Marfa. Where the Chinati’s minimalist works are in perfect harmony with the landscape producing a transporting, physical experience, the Stark museum is a white box of sunset dreams. And the effect is heady and cerebral, an elaborate and surreal articulation of the cliché “the grass is always greener.” Perhaps one day in El Paso or Albuquerque there will a museum of East Texas and Louisiana art, like the planned “Black Taj” to face the white marble Taj Mahal across the river.

‘Branding the American West: Paintings and Films from 1900-1950’ is on view at the Stark Museum of Art, Orange, TX, through Sept. 9.

1 comment

“The best, such as Frederic Remington’s highly emo He Shouted His Harsh Pathos at a Wild and Lonely Wind, But There Was No Response (opening on tour for The World is A Beautiful Place and I’m Not Afraid to Die) ” i really just read this here?