The following is a conversation between Glasstire’s Christina Rees and Brandon Zech about Nina Katchadourian’s solo show at the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin.

Christina Rees: Brandon, you just wrote a pretty scathing review of a show at The Contemporary Austin, but to explain your anger at Garth Weiser’s paintings, you opened the piece with: “It could be partly my fault—I did come to the exhibition immediately after spending hours at the charming and clever Nina Katchadourian show at the Blanton…”. As far as I know, this was your third time to see Katchadourian’s show. You don’t even live in Austin, and yet you keep going back. What gives?

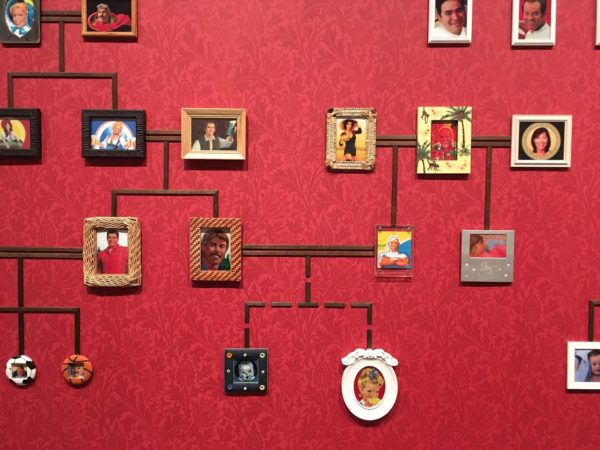

Brandon Zech: You’re right—I’ve been to Katchadourian’s show on three separate occasions. What I enjoy about it is that all of the work in the exhibition offers so much to unpack while at the same time, none of it is convoluted or inaccessible. Take The Genealogy of the Supermarket, a huge wall installation that maps imagined familial relationships between the characters on food packaging. On the surface, it’s funny and clever—creating relationships between fictional characters that we encounter whenever we take a trip to Walmart—but the more you dig, Katchadourian’s political and social commentary comes out in full force. Like the relationship between Aunt Jemima and Quaker Man; while seemingly innocent, Quaker Man looks frighteningly similar to a plantation owner. Other connections are a bit more obscure, like the Jolly Green Giant’s marriage to Mia, a.k.a. the Native American woman on Land O’Lakes butter. I think Katchadourian’s best trick is that she makes it fun for the viewer to get from point A (the initial looking) to point B (her deeper implications).

CR: I saw the show and really liked it, too. And along the lines of what you’re writing, what strikes me most about her work is that it has that lightness of touch, but that’s almost deceptive. She’s actually very careful, and she’s thorough. I thought a lot about what she had to get prepared in advance to make the full-on music videos in the airplane bathrooms.

The charm of the work is that it feels like play, but if you spend some time with it you do find the substance, and the making of it is far from effortless.

So Katchadourian’s talent is twofold: one, she notices things most of us overlook and she finds the poetry in those things and brings it out into the light (often with humor, which is so under-appreciated in art); and two, the work is meaningful without being heavy handed. But with that, what did you have the most emotional reaction to in the show. Did you pick up on any melancholy?

BZ: While emotional reaction for this show is hard to quantify, since so many of the pieces have an air of reminiscence, I’d have to say the Seat Assignment music videos that you mentioned affected me most. Namely, they made me overwhelmingly happy, which is an emotion that, even as an art enthusiast, I find is hard to come by. At the risk of sounding tremendously cheesy, I have to admit that, after my third time walking through the show, my cheeks hurt because I was smiling the entire time.

This, of course, doesn’t mean that there weren’t melancholic moments. Katchadourian’s choice to recreate in miniature the Twin Towers (while on a plane, no less), is a gesture that harkens back to an all-too-recent nightmare. And her audio installation, composed of the inaudible blips and crackles of transmissions from the Apollo 11 mission and installed in a pitch-black room, laments how big the universe is and how alone we seem to be in it. Was there another piece that you feel detracted more from her usually humorous tone?

CR: I think more than any particular piece being melancholic for me (though the Under Pressure video had me pretty close to tears at one point, despite the humor and absurdity of it; call that the power of music), is that by realizing just how tuned in Katchadourian is, I lament that most of us are so far from that. We’re distracted, and self-absorbed, and not fully inhabiting our immediate surroundings. We aren’t appreciating the moment, and that trend is getting worse. But she’s hyper-aware of it, and I think spending time with her work can—and this may seem like a stretch to some but it’s true—retrain your brain and your perceptions, to help you see things again. And feel things. Good art can do this. Her show is a particularly good example of this phenomenon. I walked out of it both more hopeful and more regretful.

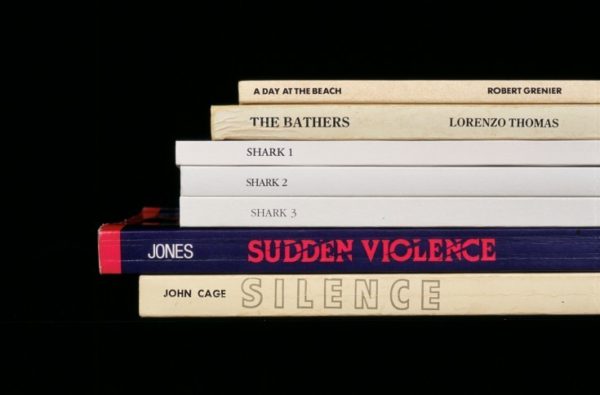

BZ: On that point, Katchadourian’s way of thinking makes you feel that it’s okay to be tuned in and find humor—and art—in everyday interactions. In this respect, I think it’s interesting how analog her exhibition is. Yes, her iPhone allows her to make photographs and videos on a plane, but ultimately, technology doesn’t factor that much into her work. Her Sorted Books are a perfect example; many artists cull the internet for language to use in creating tongue-in-cheek micro poems. Instead, Katchadourian uses a medium (books) that has been around for hundreds of years. And then, at the end of the exhibition, there is an interactive education station that gives you the opportunity to create your own stacked book photographs. All of this goes to say that Katchadourian is actively encouraging you to look away from your phone and interact with the world around you—and she makes it clear that you can do this just as easily as she does.

CR: Sure, although most of us aren’t so clever as to think about what to do with these observations—how to spin them into gold. It takes an artist’s mind to think to mend an actual spider’s web with her own red stitching, or to make a piece about what it takes to trade speaking accents with her immigrant parents through Accent Elimination. Using what you’re calling analog processes, i.e. the hard materials at hand, she’s beyond just resourceful, and her process is ongoing. Of course this is about not just seeing things many of us don’t, but also recognizing patterns across places and time.

BZ: You mentioned Accent Elimination, a six-channel video installation inspired by posters Katchadourian came across in New York that advertised courses on how to adopt a more “correct” (i.e. American) way of speaking English. (Side note: I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that the Blanton recently acquired this piece). When Katchadourian uses language and text, one of her strengths is that she doesn’t try to make broad sweeping statements; instead, she lets language do what it does best: communicate individual stories. So much text art seems to beat Jenny Holzer’s truisms to death. The power in Katchadourian’s work, however, is the personal connection that comes from the text of an individual; we relate better to personal anecdotes than to cold, narrowly interpretable statements.

CR: She’s pretty wide-ranging with her use of language or text though. She can make the random seem more personal and direct-—warmer—as in the series where she rearranges people’s books on their bookshelves so that there’s a surprising connection or meaning between titles. But her talking popcorn piece is about a search for possible patterns or meaning being made out of the completely random. It’s knocking on the idea that if a chimp were to sit at a typewriter and type for eternity, he would eventually type every book in history.

BZ: Yes, totally. Some instances of language, like Talking Popcorn, are much more random—hooking up a microphone with a morse code to text translator means that literally anything could happen—real language could come of the blips and dashes from the pops, or it could be gibberish ad infinitum. I particularly enjoyed the fact that the first-ever English word spoken by the machine was “WE”—it provides a funny sense that the computer might just be self-aware.

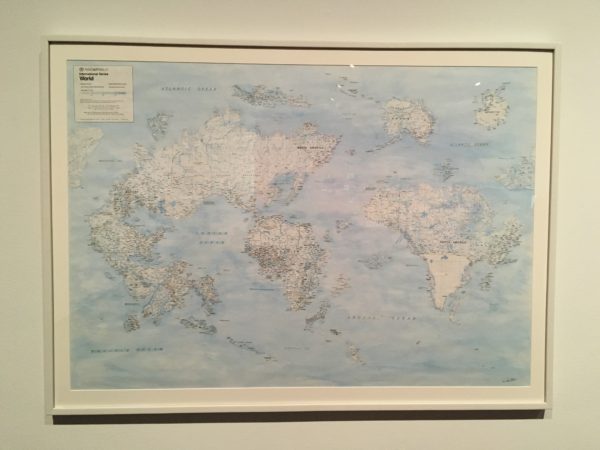

What about the more constructed use of text within some of the earliest works in the show, her cut and restructured maps? Do you think the included text added to the controlled chaos of rearranged continents, or did it detract in the sense that it was still demarcating a sense of place?

CR: I think it’s incredibly deliberate, what she’s doing with the map. We apply language to everything in order to make sense of the world and to organize it and our thoughts and feelings, about everything. The map is a simple and very effective way to raise the question of labels and preconceptions and prejudices, and how—I’ll use this word again: absurd—it is that we’re so attached to these categories. We go to war over them. She’s got a Dr. Seuss wisdom happening here. People are people no matter where they’re from or where they’re headed. Yet humans throughout history are so determined to label everything, for better and for worse, and often it is for worse. Do you think I’m reading that right, or have I over-analyzed it?

BZ: I think we’re on the same page, but to me, it harkens back a little more to the idea of Pangaea, continental drift and absurdity regarding the temporal aspect of our society. We’ve put in all this work to create maps that attempt to make sense of where we are in the world, but eventually, what we use today will become obsolete. There’s an overarching timelessness that makes everything we do so meaningless, but at the same time, at the risk of sounding cliché, every moment is valuable.

On that note—there is a preciously small amount of time left to see this exhibition—it closes this coming Sunday, June 11. It’s worth a visit, worth a day trip, and worth the time. Given the chance to see it again, I would in a heartbeat.