Agnes Martin, The Book, 1959. Gouache and ink on paper mounted on canvas, 23 15/16 × 17 7/8 in. (60.8 × 45.4 cm). The Menil Collection, Houston.

The Coenties Slip is a two-block area off the East River on the south end of Manhattan Island. In the 19th century, it was an artificial inlet for docking ships, but later it was filled in and became a two-block street between Pearl Street and South Street. In the 1950s, artists rented studios in the street’s former industrial buildings and sail-making lofts. This group show at the Menil in Houston includes work by Agnes Martin, Ellsworth Kelly, Jack Youngerman, Chryssa, Lenore Tawney and Robert Indiana, all of whom had studios there. In the pamphlet that accompanies the exhibit, curator Michelle White speculates, “Those affiliated with the Slip approached abstraction with a willingness to let the natural world seep into their compositions… ,” which seems like a strange thing to write about this group of artists. “Nature” is not a word I would associate with many of these artists, and Coenties Slip as a location is about as urban as one can possibly be.

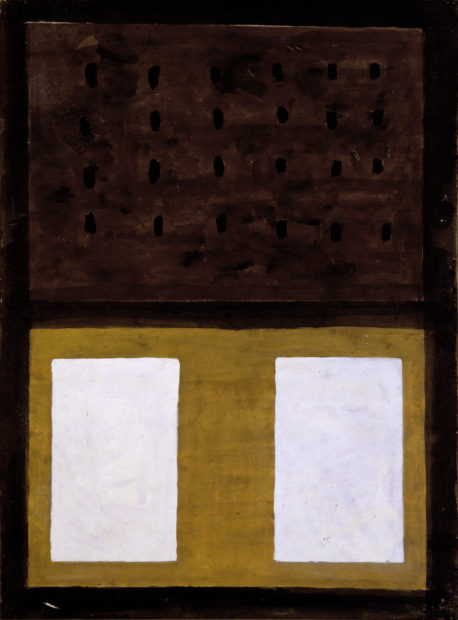

Jack Youngerman, Untitled, 1955. Oil on burlap, 57 9/16 × 35 13/16 in. (146.2 × 91 cm). The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

And in fact, it’s hard to see much similarity between these various artists. I wasn’t at all familiar with Jack Youngerman or Lenore Tawney before seeing this show. If I had to characterize their work, I’d say Youngerman was a hard-edged abstractionist who was influenced by floral forms (in regards to Youngerman at least, White is right about the influence of nature) and veered towards Op Art it times. Tawney produced a lot of work with textiles and collage, some of which is here.

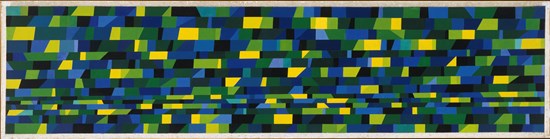

Ellsworth Kelly, Rouleau Bleu, 1951. Acrylic on unstretched cotton canvas, 17 1/2 × 117 in. (44.5 × 297.2 cm). Private Collection, Houston.

Before you enter the gallery, there is a long horizontal abstraction, Rochetaillée (1953) by Youngerman. Composed of geometric fragments is green and yellow, Youngerman’s work relates to Ellsworth Kelly’s, especially Kelly’s Rouleau Bleu (1951), which is facing Rochetaillée as you walk into the gallery. But these paintings were done while the artists were still living in Paris, studying art on the G.I. Bill.

Chryssa is best known for her pioneering work with neon. I mentioned to a friend that she was in this show and he said that she’s the kind of artist who always has one work reproduced in textbooks. Maybe she’s due for a reevaluation. The Menil has several of her works in its collection. The works in this exhibit show her promise more than her mature work. Small white letters (ca. 1960) is a group of wooden letters painted white in a vertical box, facing edge-out so you can only identify the letters by looking at them from an angle. The letters recall Jasper Johns, and the glassed-in box evokes Joseph Cornell. A similar work in the show is Study on Light (1962) which is also made of mass-produced letters glued to a canvas and painted white.

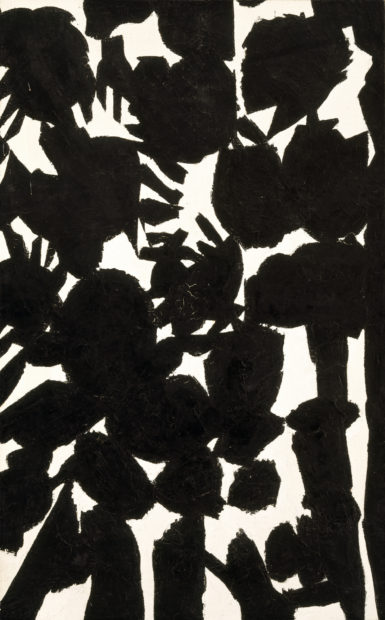

One of the surprises of the show is Teasel (1949) by Ellsworth Kelly. He was still living in Paris then, so it’s not really a Coenties Slip work. It’s an ink drawing on paper of thistles in silhouette, and it’s surprisingly realistic, given the abstract severity of Kelly’s subsequent work. White writes, “While Kelly lived [at Coenties Slip], he cultivated a flower garden on the roof in order to have foliage to draw, a practice he maintained throughout his career.” It’s a shame that the Menil doesn’t have any drawings of flowers from the Coenties Slip period. They do have a number of sketches and collages that show Kelly working through ideas that would later become the paintings he is best known for. In the show, these are called “tablets” (perhaps from “writing tablets”?) and they included drawings of shapes (like Xs) and collages of photos clipped from newspapers of distinctly shaped objects (like triangular sails). A group of Kelly’s ’50s-era abstractions are clustered in the lobby and it is useful to compare them to the tablet sketches. While drawing flowers might have been part of Kelly’s development, these sketches are much more important in understanding Kelly’s art overall.

![Ellsworth Kelly, Tablet #65 [Five Sketches], 1960s. Printed paper on paper, 15 1/2 × 21 in. (39.4 × 53.3 cm). The Menil Collection, Houston,](https://glasstire.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/2003_005_057_M-600x454.jpg?x88956)

Ellsworth Kelly, Tablet #65 [Five Sketches], 1960s. Printed paper on paper, 15 1/2 × 21 in. (39.4 × 53.3 cm). The Menil Collection, Houston

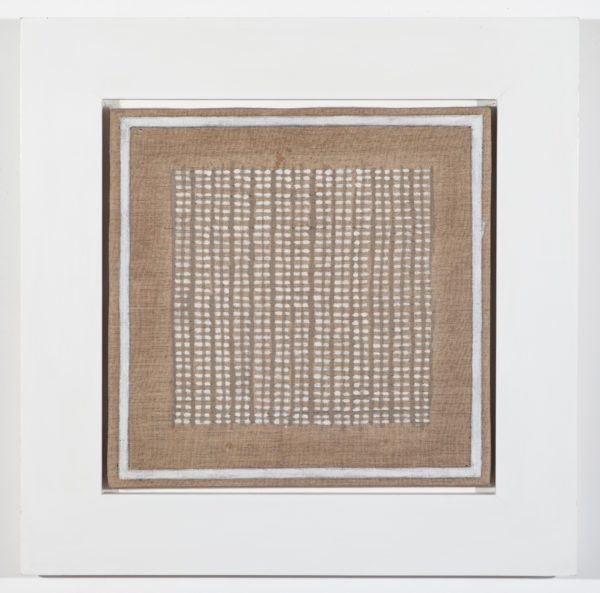

Agnes Martin, Island No. 1, 1960. Oil on linen, 12 × 12 in. (30.5 × 30.5 cm). Private Collection, Houston.

Agnes Martin moved to Coenties Slip in 1957 and stayed until 1967, when the buildings were torn down. She was the last of the group to keep working there. The exhibit starts off with an untitled 1955 painting by Martin that may remind viewers of Paul Klee. Her linework in it is whimsical and delightful, and the only part of it that suggests the future Martin is the horizon line. The other Martins in the show suggest horizons and grids as we might expect from this artist, but they aren’t as rigorous as we’ve come to expect from her work. Horizon (1960) is really a series of horizons, each with triangular hills projecting upward from them, light blue against a dark blue “sky.” Island #1 (1960) is an early grid painting, but quite painterly compared to her later graphite and acrylic paintings.

The problem with making an exhibition out of this disparate group of artists is that their work is so dissimilar. They don’t form a school. I think the idea that the “natural world” was somehow a uniting factor is dubious. The main thing they had in common artistically is that they turned their backs on the New York School (except for Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman and Ad Reinhardt). But what they had in common was that they were all in this one place at one time—the show’s accompanying literature features several photos of the artists hanging out together in the studios, on the roof of one the buildings, and in Counties Slip Park. They were exceptional artists and were a community of friends, and that seems like reason enough to put together an exhibit.

Through August 6 at the Menil Collection, Houston. Images courtesy of the Menil.