Every time I visit the Modern in Fort Worth, I make a point of parking to the far left of the museum, and on my walk to the front door, I at least brush my hand over the Serra as I pass it. Often I’ll go ahead and walk into it, and maybe whistle up into its echoing vortex. (It’s titled Vortex.) I’m not superstitious. This is more of a personal reminder of our collective custodianship of artwork, and the rare opportunity to get tactile with it. I make no excuses for its phallic shape or the idea that Serra The-God-of-Rigor makes work that demonstrates power. I don’t find his sculptures threatening. I find them parental, engulfing, familiar, and reassuring. You know exactly how they’ll feel before you touch. His oxidized behemoths are our direct bridge to the elemental—to some carbon physicality we and everything else in the universe have in common—as though they rose up from the earth’s core and cooled on contact with its surface, or came down from Mars and settled as sentinels—a calm witness to all our fickle shenanigans. Vortex is a Dune sandworm you can settle into the belly of, and who talks back to you. And being in Texas, its skin is almost always warm.

Despite this appreciation, I walked into the Serra print show at the Nasher in Dallas with no expectations, because when an artist is primarily known for something other than prints or drawings, works on paper can feel entirely secondary to the the main event. But why would I have ever underestimated the God of Rigor? This show is gorgeous. Serra approaches his printmaking (which he’s undertaken for decades) with the same gravity, precision, and pursuit of mass and presence as when he employs tons of steel. I get the feeling nothing leaves his studio without a 200-point inspection. (I like this natural counterpoint to scruffy, tossed-off art. Someone has to set the original calibration—the conceptual and physical bottom-line of art thoroughness—so that everything else can fall into place along a spectrum.)

The Nasher has appropriately blacked out its usually glowing ceiling and windows in the gallery, and lit the show with some taste for drama. Walking into the space, into the rhythmic phalanx of dark graphic shapes looming off the walls, creates a physical sensation that for me feels akin to walking into the heart of a giant subwoofer. You can practically hear Lou Reed’s Street Hassle in its 7th-inning transition to a thudding bass-line as heavy as mercury. And again, this is a grounding experience, not a menacing one. But I can’t speak for everyone.

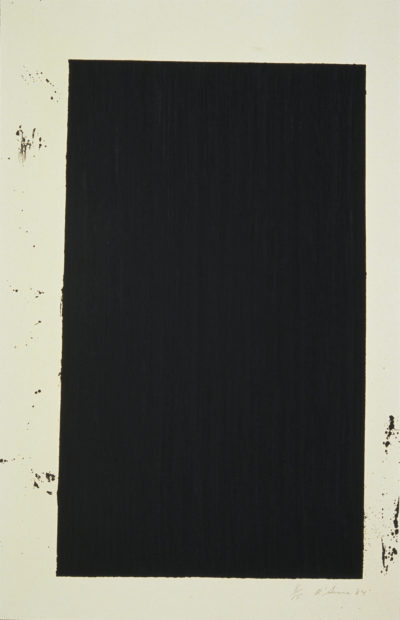

The other sensation for me, especially as you approach the larger, encompassing works (which have the full authority of painting, by the way) is like sinking into a vat of black oil, in a surprisingly therapeutic and sensory deprivation way, and this makes more sense as you study the oily, rumbly surfaces of the prints Serra made with (truly) pounds of ink, bricks of melted oil sticks, and ground silica. Many of these are hand-made reliefs as much as they’re mechanical prints.

The great poet and Nobel Laureate Derek Walcott died a day or two before I saw this show, and one of his quotes about poetry in his Times obit came back to me as I took in the Serra room:

I come from a place that likes grandeur; it likes large gestures; it is not inhibited by flourish; it is a rhetorical society; it is a society of physical performance; it is a society of style… If you wanted to approximate that thunder or that power of speech, it couldn’t be done by a little modest voice in which you muttered something to someone else.

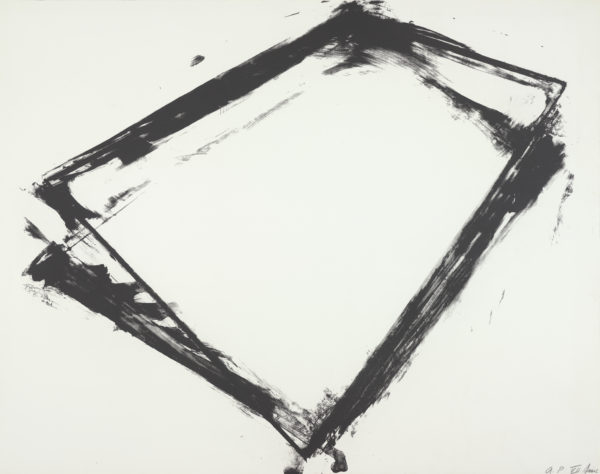

Serra is always grand; he seems incapable of anything less. Even when he’s experimenting. His earliest prints here, from the 1970s, were made as he was learning the ropes at Gemini G.E.L. in Los Angeles, and sure enough, they’re more gestural and allude more directly to perspective. You can still see the idea of an originating drawing. They seem more interested in communicating movement, as the dark-but-open near figures seem to skip (through time) and turn on the paper. They’re better than nice. For early works, they’re incredibly deliberate and resolved.

But it’s in the 1980s, as with the eight-and-half-foot tall Robeson, that Serra ditches all sense of drawing, and fully reconciles his obsession with pure shape and mass as found in his sculptures, and invents his approach to laying this down in two dimensions. With these, no 3D reference is needed. These aren’t pictures of things—not really. They don’t move as much as hum. And Robeson is as present and enveloping as a building.

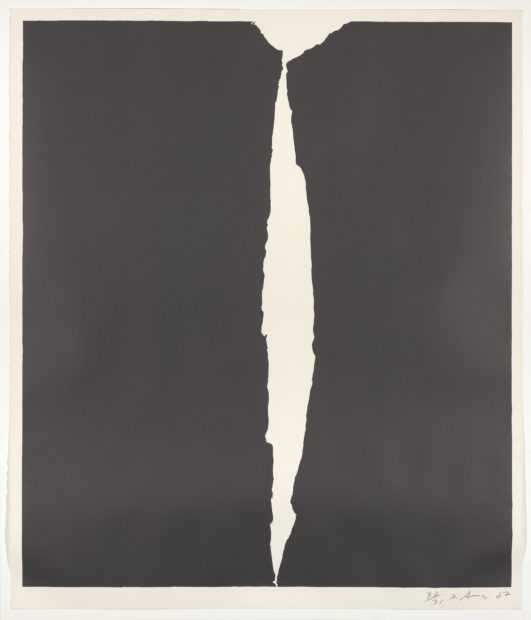

Not all of the prints approach the size of Robeson, but they all live large. Bo Diddley, from 1999, is four feet across yet has the gravitational pull of a black hole. Penn. Ship (1987) might well be my favorite, in that you can enjoy it as a pure flat (and wonderfully sexually suggestive) graphic as much as you can project it into three dimensions and imagine yourself walking through it towards the light—just as you can walk through the Nasher’s own giant Serra out in the garden.

The term I assume a lot of people would use for this show is ‘immersive.’ But that’s the thing with Serra: you have to experience his work in person—the sculptures obviously, but also the prints. You’d think seeing reproductions (say, on this digital page) of his mechanical reproductions would give a reader a pretty good idea of how the work comes across. No. You need to walk up to these to take in their full charisma. You’ll find them generous, a bit foreboding (charisma requires this), and patient. Even just one of them could hold a room—and would change the atomic feel of a room, the architectural disposition of it. I’ve always liked prints, and the very notion of printmaking, but I didn’t know until now that a print could do this.

Through April 30 at the Nasher Sculpture Center.

1 comment

Word !