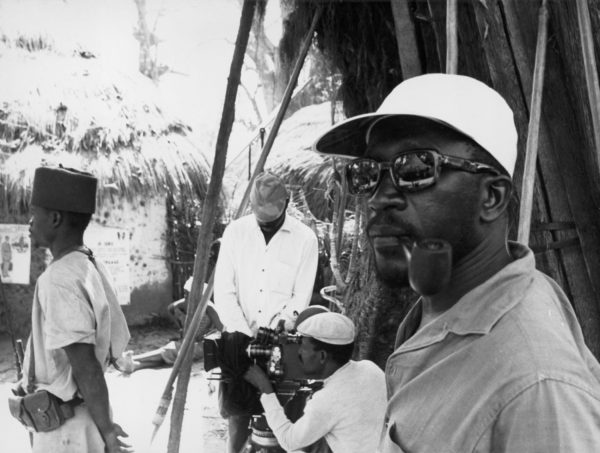

This Sunday afternoon, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston will present a pairing of two early films by Senegalese director Ousmane Sembène. His acclaimed first feature, the 60-minute Black Girl (La noire de…) (1966), won the Prix Jean Vigo and international critical acclaim, launching his four-decade filmmaking career and opening doors for African cinema. The lesser-known 20-minute film The Wagoner (Borom sarret) (1963) was his first film, and is considered the first film made by a black African. Both are poetic, heartbreaking works of realism. Both are powerfully of their time and place, yet remain contemporary in their artistic and social relevance. And both of these rarely screened films will be shown here in crisp new digital restorations.

Ousmane Sembène was an accomplished novelist as well as a labor organizer before he turned to filmmaking in his 40s. A critic of colonial oppression and keen observer of the inequalities that persisted in Senegal after its independence from France, Sembène considered film to be a more effective medium than literature for reflecting the life and conscience of his people, reaching wide audiences, and, he hoped, for catalyzing social change. He was a kind of cinematic griot, equally committed to reflecting the details of daily life within unfavorable social conditions as he was to nudging the various power systems that created and perpetuated them.

Black Girl and The Wagoner should be more recognized than they are–at the very least, within the contexts of landmark independent films of the 1960s. In both, Sembène turned common limitations of low-budget filmmaking into great advantages. His nonprofessional cast members have a striking yet restrained natural presence. The looseness of sound synchronization in the films creates an interesting blurring of the lines between inner and outer dialogue. Along with the films’ great black-and-white cinematography and subtle use of music (alternating between West African and European forms to reflect dual atmospheres), these elements create a sense of sustained longing and suspended dream limbo that’s inseparable from the realities of the films’ grim circumstances.

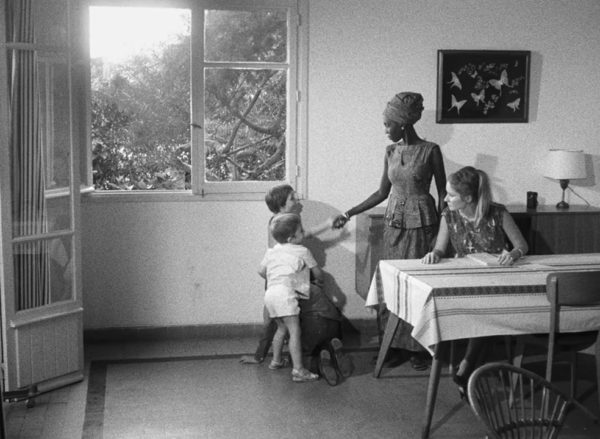

The Wagoner (Borom Sarret) follows a day in the life of a villager on the outskirts of Dakar as he struggles to make a living transporting people in his horse-drawn cart. It’s a very good prelude for Black Girl (La noire de…), which expands and shifts the predicament. In it, a young Senegalese woman, Diouana, has moved from Dakar to Antibes in the French Riviera to work as a live-in maid and nanny for a wealthy white couple there. Her story is told by alternating between her uncomfortable situation as a domestic worker in France and fragmented memories of her life, love, and youthful expectation back home.

While the English title of the film is Black Girl, its original French title is La noire de… . The subtle, open, unanswered possessive at the end of its original title—truncated for simplicity in English—is actually everything. This film does not define a black girl, nor really this black girl. It does the opposite. It poses, or exposes, an impossible, multi-layered question about her. The black girl from/of…what? where? who? Who is she. How is she defined. Where is she from. Where does she belong. To whom does she belong. That these questions of identity, connection, placement, and possession are unanswerable is, to me, the point of the film, and of its larger issues—social, political, and existential. The addition of one tiny word, followed by an elipses—“de…”—is a brilliant key to this work and to Sembène’s work in general.

****

Black Girl (La noire de…) and The Wagoner (Borom sarret) screen together at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston’s Brown Auditorium on Sunday, Feb. 26 at 2 p.m. More information here.