Damn, I’m depressed about the stagnant, rent-seeking, extractive stupidity of this corrupt social order. But nothing helps me fight my fear-of-fascism blues more than to take a deep breath and realize that yes, we’ve all been here before. I try to remember that in all times and places it’s a shared revolutionary grasp of history that allows people to wake up from their state-induced daydreams and nightmares and create a new historical narrative that pushes human existence into the future instead of imprisoning it in the past.

The prints and drawings in Vignettes: Masterworks on Paper 1520 -1870 at the MFAH tell the story of the rise of European power in the Renaissance between the 16th and 19th centuries. The 16th century, where the exhibition opens, was a time of violent religious and political upheaval and technological revolution. Martin Luther, a disillusioned lawyer-turned-monk launched (probably more or less unintentionally) a revolution within the Catholic Church known as the Protestant Reformation. In his 95 Theses Luther asserted that a Christian’s inner life—his feeling of faith rather than his social status or his actions—was the only true measure of his piety. To rub it in, Luther translated the Latin Bible into common German. He let the cat was out of the bag. The citizens’ ability to read the Bible in German and the belief that salvation resided in a personal relationship with God would destabilize the religious and political order of the Catholic Church. Plus it must have just been painfully obvious to most people that huge numbers of popes and priests had become greedy, whoring frauds.

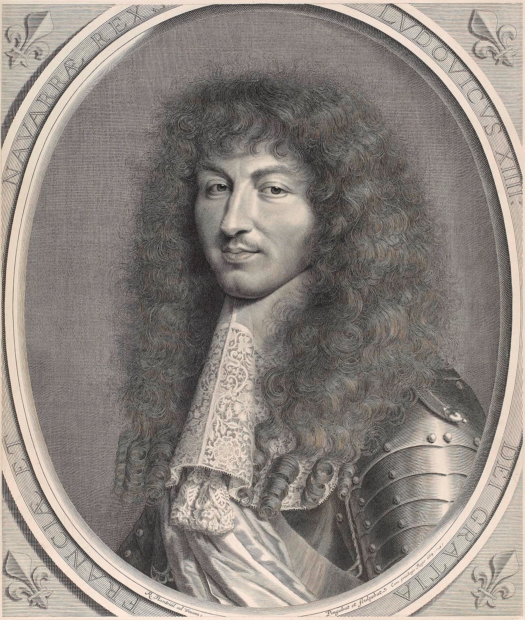

Nicolas Beatrizet, after Niccolo della Casa, after Baccio Bandinelli, 1548, engraving on laid paper.

Nicolas Beatrizet’s 1548 engraving, after a self-portrait by Baccio Bandinelli, tells another side of the story of the 16th century. Martin Luther’s attack against the hypocrisy of church officials who organized orgies and waged wars like military generals wasn’t the only blow against the dominant religious ideology that had governed Europe throughout the Middle Ages. European artists, writers and politicians, always surrounded by the ruins of an antiquated system that had become opaque and inexplicable to them through nearly a thousand years of neglect, began to rediscover many of the founding philosophical texts that had allowed the ancient Greek and Roman empires to expand and build wealth and power.

The historian Stephen Greenblatt gives a semi-fictional account of this process in his Pulitzer Prize-winning 2012 book The Swerve. Greenblatt’s readable, much-criticized and much-praised history tells the story of Poggio Bracciolini, a papal emissary sent by the central organs of the Catholic Church to scour obscure countryside monasteries in search of ancient texts which had been spirited away and preserved by monks throughout the Middle Ages after the dissolution of the Roman Empire. Poggio discovers the Roman poet Lucretius’ poem On the Nature of Things. To read Greenblatt, religion was pretty much doomed and the Modern world was born in that moment of discovery. It’s an oversimplification but it has its kernel of truth. Throw in the invention of the printing press a hundred years earlier, and a recipe for mass empowerment against both kings and popes wrote itself.

Printed a century after Poggio’s chance recovery of the ancient world, Beatrizet’s copy of Bandinelli’s self-portrait shows just how quickly the artistic obsession with that era’s classicism moved the visual arts from a schematic, highly symbolic representation of Christian ideology to a more or less secular vision of a successful professional artist surrounded by unintentionally silly plaster models of naked Roman action figures. A hundred years earlier the position occupied by the artist in this image would have been reserved exclusively for either the Christ or Madonna. But in this image we can see (even if it is cloaked in egotism) the revolutionary idea that human beings—not nature, not gods, not markets—are at the center of their own reality, and are capable of making their own decisions about how to live and govern themselves. This was the promise of democracy back then, and the promise of democracy today. It’s an old story. It’s the moment when a culture wakes up and realizes that the old moral order has seized up, outlived its usefulness and become hard and cruel. We’re at that moment again. It’s never been clearer that our leaders have exchanged spiritual terrorism for economic terrorism.

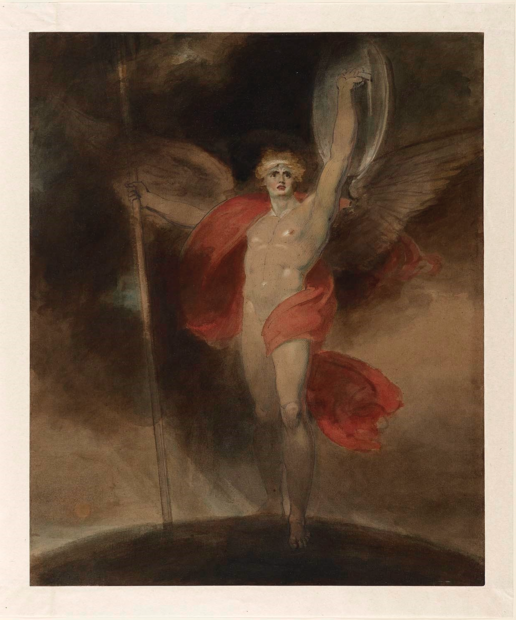

Look at this guy:

Robert Nanteuil, Portrait of Louis XIV, 1664, engraving on laid paper, state II/V, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

Louis XIV was your classic iron-fisted late Renaissance monarch. He wasn’t a fan of Protestants, so during his reign he initiated a terror campaign against French Huguenots. The Huguenots were Calvinists and, well, all you have to do is look at Louis’ coiffe to see that greed and concentration of power are written all over his curly locks. Louis XIV reduced his Huguenot population from around two million to less than a million through deportation, conversion and murder. Today we call this ethnic cleansing. It would be another hundred years before enough French people got sick enough of this kind of bastard that they would revolt and go on a killing spree, only to end up with a tiny tyrant, a European war and another hundred years of progressively weaker and lamer kings. Turns out there are better and worse ways to stage a revolution. Somehow this all feels so… familiar.

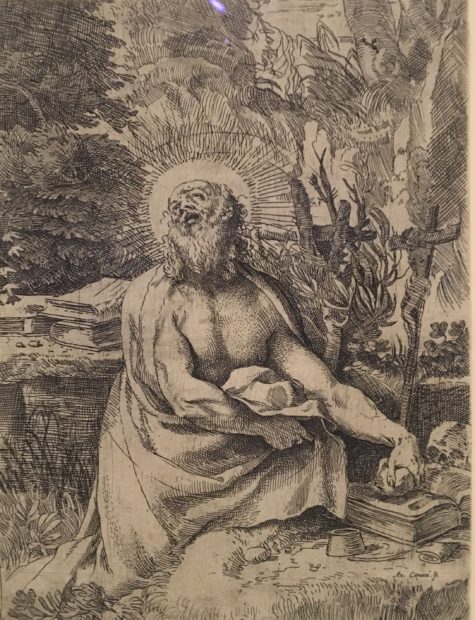

Richard Westall, Satan alarm’d, c. 1790s, watercolor, pen and ink, and gouache, over graphite on laid paper, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

Revolutions don’t disappear when they’re quashed. They go underground. Satan Alarm’d, a late 18th-century watercolor drawing by Richard Westall in the style of William Blake is pretty queer. Times of revolution always usher in new language, so if the word ‘queer’ is troublesome to some, we can pretty easily substitute it with the word Romantic. Once it appeared, Romanticism never disappeared. It fuels radical youth culture to this day. In broad, general strokes, Romanticism privileges the inner moral experience of human beings over external objectivity. Westall ran in Byron’s circle, was a successful illustrator and earned his keep in his early years employed as Queen Victoria’s drawing instructor. (Ah, the days of patronage.) Westall’s drawing illustrates the moment in Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost when Satan, despite being defeated by God, nevertheless stands in proud defiance of that most ultimate of ultimate patriarchs. You don’t have to look any further than Westall’s shiny, muscular, androgynous Satan to understand that the subversion of rigidly defined gender roles—as a weapon of resistance against regimes that would attempt to control the identities of their populations—is not a particularly new phenomenon.

I admit it’s questionable to graft one historical era onto another. The fit is often awkward because historical specificity and the contradictions inherent in human behavior tend to make direct comparisons problematic. But I’m going to do it anyway. Let’s imagine that the fight for workers unions, civil rights, and welfare programs as reformations on the way to a more just vision of democracy and economy is an ongoing effort that can never be fully achieved. Now let’s imagine the neoconservative order that has characterized the political landscape since I was born as a counter-reformation meant to claw back control for an ancient order characterized by racial distinction and rigid class immobility. This conflict isn’t new, and it doesn’t have to be the end of the world. The invention of the internet and the increasingly clear evidence of a creeping neo-feudalism from a wide range of economists including Joseph Stiglitz in America and Thomas Piketty in France (among many others) suggest that this dark moment, like those before it, is a moment of extreme danger but also incredible opportunity. It’s the responsibility of artists to write the narratives that transform this new knowledge and technology into cultural, political and economic wisdom. Are we up to the job?

Through April 16, 2017 at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston.

2 comments

You just reminded me, must read “The Swerve” again. Great article, as always. On another note, what then when robots come in full force?

I enjoyed your observations about the artworks and that you drew connections between these historical images and what is going on today. Will we learn from history or be condemned to repeat it? Unfortunately, it seems like the latter is usually what happens.