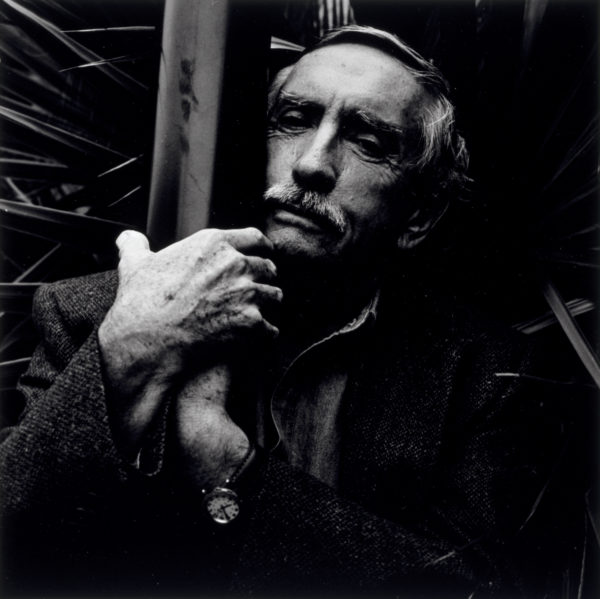

Suzanne Paul, Edward Albee, 1999, gelatin silver print, printed 2001, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, gift of Clinton T. Willour in memory of Kaye Marvins. © Estate of Suzanne Paul

When the great American playwright Edward Albee died at age 88 earlier this month, the art community in Houston took special notice due to Albee’s connection to the city and its art: from 1989-2003 Albee taught every spring semester at the University of Houston in the Playwrights Workshop. His life partner, Jonathan Thomas, was a sculptor; and Albee was deeply interested and invested in art throughout his long life.

Here are a handful of remembrances of Albee’s time spent in Houston, by those in the art community who knew and interacted with him.

Rachel Hecker, artist: I remember Edward as being kind and generous to young artists, and always interested in what was going on. I found him wandering in and out of the painting studios at UH on several occasions, motivated only by his own restless curiosity. That this curiosity extended to the developing work of students, and the processes of making in particular, speaks volumes, I think.

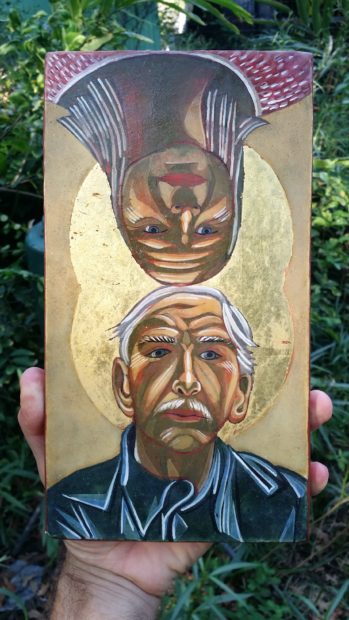

Nestor Topchy, Double Portrait, Edward Albee and Elizabeth McBride (2006). Tempera and gold leaf on wood. 5.5″×10.5″

Nestor Topchy, artist: I think Edward Albee and I met around the time I was contemplating leaving Houston following graduate school at UH, but I had postponed that to have a show at Hiram Butler gallery in about 1988. Edward visited my studio at Commerce Street; I don’t remember if someone had made an introduction or not and he’d said, “You remind me of Nureyev,” probably because I went around in just shorts and at 22 had an athlete’s physique. We talked about nonobjective art and the East Village scene and how the art scene today was calcified and stratified, etc. Edward liked coming by because he’d felt the energy was inviting in a similar way as the NY scene in the ’60s.

I liked him instantly because he had no fear and was all there, genuine and kind despite his reservations about human nature, or in addition to his insights he was compassionate.

Around 1991, I think, Edward told me to apply “only as a formality of course,” and come to his Montauk barn for a summer residency but “just you, not my retinue,” which was hilarious, as that much mayhem while trying to work in the studio and entertain my friends would be difficult to sustain anyway.

Edward had given us a blurb to use as publicity for the compound I’d shared earlier with Rick Lowe and Dean Ruck, and now with a group of artists in collaboration: “In a world that is too safe, too predictable there is Zocalo Theater as a healthy alternative; prepare to be surprised, enthralled, bewildered and, occasionally, appalled.” This was really cool we thought—America’s greatest living playwright giving us a boost; recognizing, discovering the merit of our work.

And Edward was also there for students, not of drama, but now of UH School of Theatre & Dance, where he renamed, directed the program, and donated work from his collection, [which was] mostly Houston artists.

He brought a higher sense of art to that department and inspired Kevin Cunningham, who’d studied under Donald Barthelme previously. With my friends and collaborators Kevin, Jim Pirtle, research pioneer/saxophonist Regis Pomes and band Three Day Stubble, we’d gone to the Edinburgh Fringe Festival as the Texas Freedumb Tourists, something that would likely not have happened otherwise without Edward’s influence early on. And Kevin wouldn’t have later moved to New York to found 3LD and Jim would not have pushed a hot mess pizza across the concrete floor with his nose during the Zocalo tragicomedy Pizza, Boy whence Edward would ask Jim, “Where did you study mime?” I’m still not sure whether Edward was joking or serious.

It’s those little happenings that knit together things in a way where one change will affect all of history in an unfathomable way. I could not have appreciated Infernal Bridegroom’s (now Catastrophic Theatre’s) production of Waiting for Godot whereupon a real, wild raccoon broke into the set on opening night and hung upside down to upstage Potso, Gogo, et. al., much to the chagrin of Jason Nodler directing who then threatened to kill the raccoon. My full admiration for the absurd would never have happened were it not for Edward’s earlier introduction to plays he directed by Beckett. Edward’s version of Ohio Impromptu, Happy Days, and Krapp’s Last Tape may have had a subconscious role in my limited but persistent interest in performance art, persona, and clowning.

In around 2006 he came by my studio, in lieu of going to galleries and museums, with our mutual friend Elizabeth McBride, whom he called “my Elizabeth,” only to witness my rolling in a ginger bush while having to break up a dog fight. Edward loves animals and he stoically waited on the sidelines while I wrangled and then cleaned the dogs’ wounds.

There was a fragrant air of crushed ginger.

He and Elizabeth sat for the portrait project I’d been working on, graciously, since Edward really didn’t like representational art but out of of his respect for me he understood that this was something different. He was pretty delicate that day and we all walked slowly around the yard to see the various studios in different states of repair and construction.

The thing to be lamented and regained is dwindling transmission, direct contact, eye to eye with another person; I think this is what he and I both understood in our conversation in the ’80s around art and society—about what has changed in the American psyche and it’s now in evidence in the heads bowing down into cell phones, etc.

It would not be fair to speak for Edward, but the sense of object and presence that is shared in place and person is needed in art, and it will be more so as technology makes it easier to hide from ourselves and others, making us more selfish and narcissistic. Edward’s work is there to give everyone the good swift kick in the behind they deserve, to pay attention to what we are doing and not doing, to live fully, and an admonishment to start living, now.

Aaron Parazette, artist: I didn’t know Albee but did have one funny interaction with him.

The first year I was in the Core program he saw a piece of mine in the show and asked about buying it (the piece was two side by side vertical panels… each painted with pink and white stripes—horizontal stripes on one, vertical on the other). We talked and he told me that he liked the piece very much and we agreed on a price and then he said that he had seen a small chip on the edge of one of the panels and he asked me to fix it. The chip was a splinter from the plywood face (about 1/4 x 1/2 inch) that had come off in the tape painting process.

When the chip came off I decided to leave it as an agreeable imperfection, which was then as now part of the ethos of my work (later that same summer I would do a show at the Davis/McClain gallery titled Not Perfect). I tried to explain this to Albee and he accused me of engaging in sophistry. I persisted but he just grew more skeptical until he finally said he’d have to think about getting the piece and we ended our chat. A week later I received a postcard saying: “Aaron, I’ve decided against getting the piece. Edward.” Prior to this I had only a vague understanding of who Albee was—I knew he was a playwright who bought young artists’ work in Houston. I wish now that I’d kept the postcard, but I didn’t. The piece he was going to buy ended up being used as building material for a spray booth as I continued with my work pushing toward perfection—or not.

Fredericka Hunter, dealer: The first time Edward Albee came in the gallery we were quite excited and impressed. He introduced himself as Edward. After that he came back whenever he was teaching at U of H and working with the Alley Theatre. He came back to see the shows at the gallery and often tell us, in no uncertain terms, who we should be showing instead: usually a young artist he had visited or was collecting or was going to his residency program in Montauk. He, I suppose, would have seemed to be cantankerous to some, but I really enjoyed his brio and his emphatic energy when talking about art. It was the kind of challenge in the old-fashioned art discussion manner. It was also impressive because it was this celebrated man who, I found, to be deeply, sympathetically human and a graceful human to boot, quite attuned to others and not in a superficial way. Houston was profoundly lucky to have him here for those months of the year. He seemed to appreciate his students, and he connected with visual artists, as collector and as patron. (I have noticed that often writers are very sympathetic to visual artists.) He did great work at the Alley with their complete support and went on to win another Pulitzer Prize. Late career creativity is a great grace for any artist.

We were not friends so much as acquaintances, but whenever I had the chance to be his dinner partner, I was always touched by his perceptions and gentleness.

I have to say that his motivation for coming to the gallery was often prompted, not so much for the shows, but by his love of animals. The gallery was populated for years by Scooter, a standard wire-haired dachshund—a rescue dog—who had a distinct personality himself. It was always a surprising delight to see Edward Albee come in to the gallery, drop to all fours and call for Scooter. When I read Mel Gussow’s book Edward Albee: A Singular Journey (2000), I discovered that Albee, from childhood, considered that he related better to animals than people.

In fact Gussow interviewed Albee at the Alley after the book was published, and I remember Albee describing his writing method which was that the play would be formulated in his head—he described the characters and structure like airplanes circling to land—and then he would sit down and write it out in rather a short amount of time.

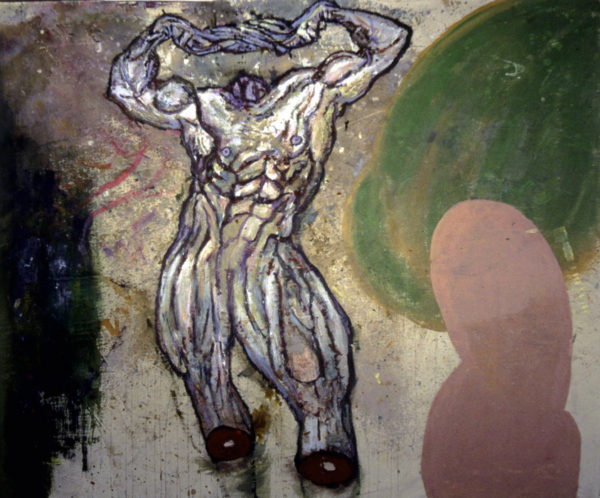

Giles Lyon, Captain America, 1990, acrylic on canvas, 6″ x 7″. Painted while Lyon was a Core Fellow at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

Giles Lyon, artist: I met Edward when I was a first-year Core fellow—I can’t remember our first meeting exactly but it was at a Glassell opening—and I invited him to my studio. He responded to the work right away and began buying my work, which he continued to do for several years while I was living in Houston during the Core and after. And he often came to my studio—so I saw quite a lot of him—he was a fixture in the Houston scene. I was also close friends with Elizabeth McBride who was very close to Edward, so we were in each other’s world for many years, including when I moved to NYC.

He had a direct, witty, wry way of talking about art and my work; he was very opinionated, and while I didn’t always agree I was deeply honored he took such an interest in me and my work. I was 23 at the time and I was familiar with his work and was somewhat starstruck. He gave me a sense of validation, often comparing my work to the abstract expressionist who he had known personally. As a young artist it can be such a struggle to believe in yourself and having someone of Edward’s stature support me critically and financially was huge. He also made a point of putting the pieces of mine he owned in public exhibitions in Houston and New York. Indeed, he helped me break into the New York scene indirectly and otherwise through people I met at the Edward Albee Foundation, where I was given a residency… which he encouraged me to apply for.

He favored a brut, raw approach to art making, tempered by a nuanced sense of balance and subtlety—hence his interest in indigenous art along with contemporary art. He often said he didn’t care if an artist’s work was valued or not; he bought what he liked. When I was in NYC I met up with him several times, and once went to a sculptor’s studio whose name escapes me, and Edward told me after leaving the dim basement space that he was not beyond buying an artist’s work just to help them out if they needed the cash. He believed deeply in supporting struggling artists. His Tribeca loft felt like a time capsule from a previous era—raw hewn beams and industrial wood floors, with masterpieces such as Walt Kuhn hung next to African masks and the like. His support helped to buttress my belief in my work, and helped me feel more robustly my lineage to the New York school and art history in general.

He was coy with an acerbic wit… but also very kind and warm and funny… but with a kind of fierce intensity just simmering below the surface. He also had an acute sense of history and the dangers of small-minded men with power. He did not suffer fools but never needed to dress anyone down, either. There was also a humility there—it seemed history was always in the room and that any artistic endeavor was serious business. One time when he arrived at my studio he told me about the time he was supposed to have lunch with Rothko and Rothko cancelled, and then hanged himself. So for this reason he never lets a friend cancel a lunch date or back out of a visit. This was delivered with his characteristic twinkle in his eye that was sad and fierce and funny all at the same time.

Another time when my work was shifting styles as I was moving away from the more austere work he had responded to—to my rorschach paintings, the first of which had very sexually charged demonic iconography— Edward commented I should stop eating spicy foods before going to bed. So there was always a seriousness and playfulness in talking about art: his or anyone else’s.

When I was a resident at the Albee Foundation, Edward was the mailman, bringing all the mail to the barn where the residents worked and lived. He set it up so there were artists and writers under the same roof, and this created a very natural salon atmosphere. I think he had gained so much from his relationship with visual artists that he wanted to cultivate those same connections with the artists and writers at the foundation. He invited me to his Montauk home a couple of times, which had an epic sweeping cliffside view of the ocean. He was living an iconic example of the kind of wealth an art career could provide, but he did so with a natural sort of modesty and generosity. He made no secret that his accountant suggested he would need to create a foundation to help him manage the wealth generated by Virgina Woolf—hence the birth of the Foundation—but it was clear he did it for the love of art and the heartfelt desire to support and cultivate the next generation of artists and writers.

I miss him, and am so very grateful for the early support he gave me.

With thanks the contributors to this piece.

1 comment

I remember meeting Edward when I worked @ Blaffer. Often I spent time with him helping pick up and move and store his

purchases. He had opinions but was always supportive and rarely failed to bring me catalogs of shows he guest curated

in NY. I appreciated his interest and guidance and was in AWE of the dialog in his work. Houston was lucky to share some

of his time. Like Aaron, I had some funny moments with him, too, usually centered around his spoken dialog about

certain genres of art. I thought it was terrific he supported many young artists others often ignored. With him it was all about the work not the politics, so to speak.