In 1970, Judy Chicago initiated her first feminist art class at California State University in Fresno. Among her students were two artists, Suzanne Lacy and Faith Wilding, who would go on to have important art careers. In 1971, Chicago and Mariam Schapiro started a feminist art program at CalArts in Los Angeles, from which Wilding received her MFA. In February 1972, Chicago and her students opened a one-month long installation called Womanhouse. Wilding did a famous performance, Waiting, there.

(Excerpt from ‘Waiting’ performed at Womanhouse, 1972)

A video of that performance is part of Faith Wilding: Fearful Symmetries curated by Wilding and Shannon Stratton on view now at the University of Houston Clear Lake Art Gallery. When I heard about this show, I thought it strange that an important American artist is having her retrospective at such a minor, out-of-the-way location. (Previous stops for this exhibition were in Chicago at Threewalls—Wilding is an emeritus professor of performance at the School of the Art Institute and Stratton was previously the director of Threewalls—and at the Armory Center for the Arts in Pasadena.) Why is it not at a bigger or more important Houston art institution?

I don’t know the answer to this, but UHCL once played an important if unexpected part in the history of feminist art. Judy Chicago resigned from CalArts in 1974 and began work in that year on her magnum opus, The Dinner Party. The Dinner Party took five years to complete and was first exhibited in 1979 at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Chicago’s intention was to tour it around various museums in the country, but only two agreed to show it and later reneged on their agreements. No one else wanted it. The reasons for its failure to get shown in the museums had to do with the expense of shipping and insuring it and the various conditions Chicago attached to showing it. It had to be shown in a very particular way with certain parallel feminist events occurring. In Houston, it was offered to the Contemporary Arts Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts and to Rice University’s Institute for the Arts, whose director turned it down, writing, “it is not the kind of exhibit that I usually present at Rice.”

Houstonian Mary Ross Taylor, then the proprietor of The Bookstore, had heard about The Dinner Party before it was completed and hoped she could help bring it to Houston. She found an ally in Calvin Cannon, dean of sciences and humanities at the University of Houston at Clear Lake. UHCL had only been established a few years earlier, and Cannon thought an exhibition like this might help put UHCL on the map. And he was right—over 30,000 people came to see it, more than half as paying customers. Taylor and Cannon raised a ton of money in advance and put together a team of more than 200 volunteers to assemble and display it. “All told, the people who donated money and volunteered their time represented the wide range of Houston’s civic involvements: political activists, art supporters, professors, staid ‘ladies who lunch’, church women, and feminists,” wrote Jane F. Gerhard in The Dinner Party: Judy Chicago and the Power of Popular Feminism, 1970-2007. In 1980, The Dinner Party was exhibited at this little campus nestled between NASA and Galveston Bay, far from the Houston art world. UHCL was the second venue for The Dinner Party, and its exhibition there created a model for subsequent exhibits in non-traditional venues. (It is now permanently ensconced at the Brooklyn Museum.)

Which brings us to today. The University of Clear Lake’s Art Gallery is tiny and not a great venue for showing art. About half of it consists of windows facing into the center of the cavernous atrium of the central structure on campus, the Bayou Building. But the windows serve a purpose—they advertise the gallery’s existence to the students passing by. Fearful Symmetries takes advantage of this disadvantage by placing one of Wilding’s most dramatic pieces right behind the window, so that it is visible to passers-by. Flow consists of two large chemistry flasks on small tables, each filled with colored liquid (water mixed with ink), with a large piece of cheesecloth stuffed in the openings of the flasks and hanging like a hammock between them.

Flow, 2010-2016, chemistry vessels, cheesecloth, water, ink

The ink has been absorbed into the cheesecloth via capillary action, slowly staining each end—one is stained red, the other end is blue-green. It’s a beautiful piece of process art.

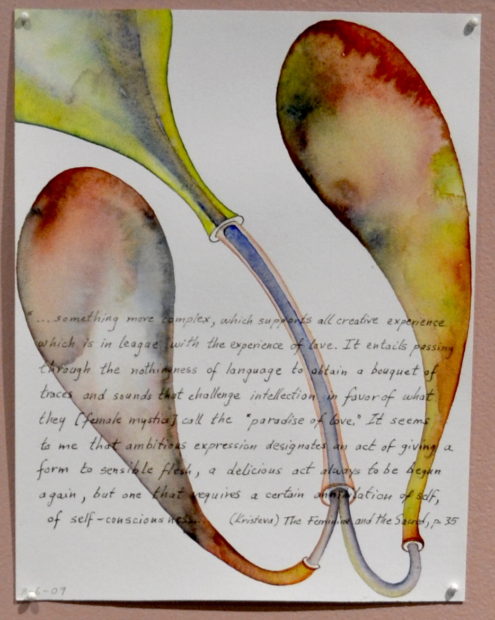

Much of her work combines text and painting. Some of the texts are her own writing, and some come from writers who are feminist heroes; for example, Julia Kristeva, Emma Goldman and Virginia Woolf.

Tears Wall detail, 2009, watercolor, ink, pencil on paper

Tears Wall detail, 2009-2010, watercolor, ink, pencil on paper

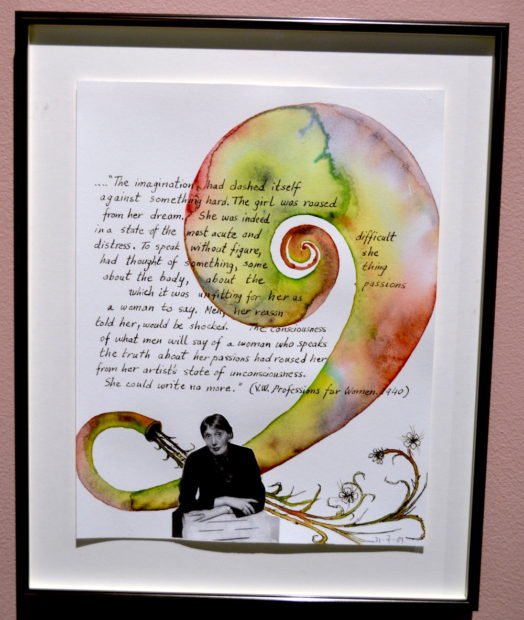

These works, Wait-with Virginia and the Tears Wall, don’t really feel like fully realized artworks to me, although Wilding has clearly applied a lot of care to them. They feel like things one might find in an artist’s sketchbook, where ideas collide with images as the artist encounters them. You’re reading Kristeva or Woolf and a passage strikes you as memorable so you write it down—the act of transcribing it by hand makes it more memorable, more your own—and you combine it with drawing or painting or collage.

Wait-with Virginia, 2010, collage, watercolor, pencil on paper

In fact, her best work in this vein in the show appears in two vitrines, which contain sketches and notes from 1978 to 1989. These combine the various pages with sculptural objects laying on top of them, including the slightly disturbing papier-mâché sculpture, Armless Mermaid.

Armless Mermaid, 1989, papier mache

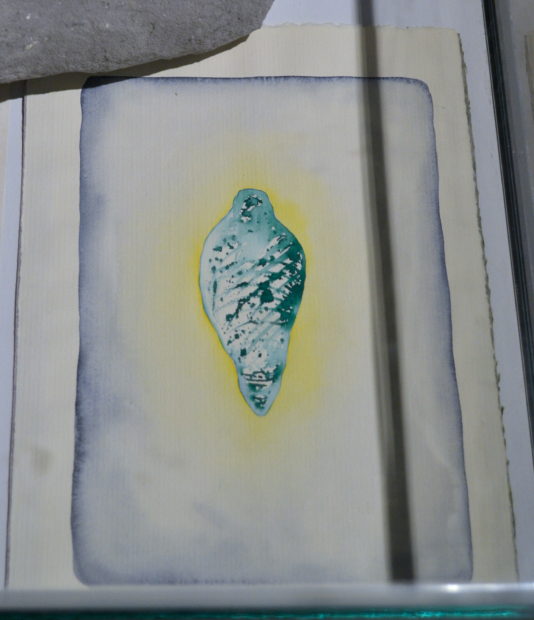

Sketch, 1978-1989, watercolor on paper

But her sketches, such as the untitled watercolor of a blue-green larval form with a yellow glow in a blue box, are striking and beautiful. Her idiosyncratic versions of natural objects like this are some of the most visually pleasing pieces in the show, including the wall of shaped paintings of mammoth leaves.

Untitled (Leaf Series), 1979, oil on canvas

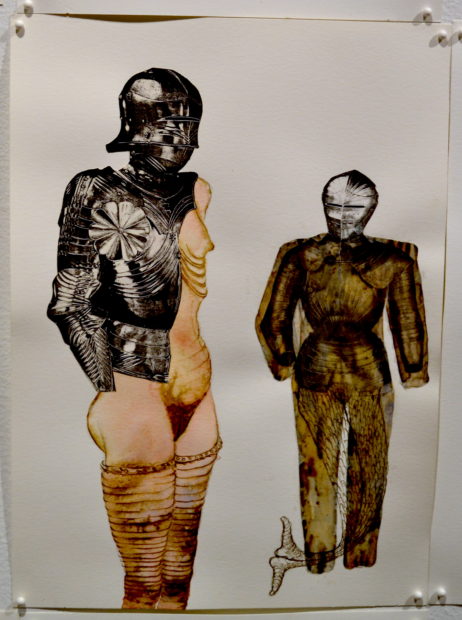

But to me the most unexpected work was the wall full of Armour Drawings. It’s a wall of 38 ink and watercolor drawings of various types of medieval armor. The imagery is aggressive and warlike, something I can imagine a teenage boy drawing. It’s a very masculine subject matter. There are helmets, breastplates, mailed gloves, armored thigh coverings and armor for horses. In addition to the armor, there are four drawings of hands, including two fists. Her watercolor technique is excellent and the combination of pen-and-ink drawings next to densely painted watercolor images make this wall stand out.

Armour Drawings, 1991-1994, watercolor, ink on paper

The very assumption that this subject is ‘masculine’ relies on the assumption that the wearer of this armor is male. But a drawing in the center of the wall shows how short-sighted this: it shows an otherwise naked woman wearing an incomplete set of armor. She is standing next to what I read as a mermaid wearing armor.

Armour Drawings detail, 1991-1994, watercolor, ink on paper

These could be interpreted as a need for women to wear metaphorical armor to survive. Of course, armor isn’t just for defense—knights wore it in order to attack their foes. A chain-mailed fist was a threat. Maybe the armor is a metaphor for defense, but maybe also a metaphor for taking offensive action.

Right next to this wall of armor drawings are Wilding’s Biodresses. Made of resin, watercolor and ink, they look like shapes made of skin, with an uncanny, disturbing texture with bits of hair and bloodvessels in it. These pieces precede the movie Silence of the Lambs by three years, but that’s what they made me think of—the character Buffalo Bill’s attempt to make a skin suit out of his victims. The dresses are combined with zeroxes of metal helmets. They precede the Armour Drawings by several years, which suggests that armor was on Wilding’s mind for quite a while.

Biodress (Embryoworld series), 1988, Xerox collage, watercolor, ink, and resin on vellum

I generally hate it when art exhibits put too much explanatory (patronizing) text on the walls, and this show admirably had none. But I feel like I could have used some here. Are the Biodresses meant to be frightening? Are they meant to look like flayed skin? Because they do. If this is by design, they work.

These were installed across from a video of Waiting. This was an important early work of feminist performance. Wilding is sitting in a chair, her upper body rocking back and forth, telling her life story by making statements about things she is waiting for. Some of her statements are gender neutral and in no way indicate a societally enforced passivity—such as about being an infant waiting for someone to enter the room, to feed her, to change her diaper. But as she moves to adolescence, her experience of waiting takes on the passivity of women in social custom—waiting for a boy to call her and ask her to a dance, for example. And it ends with with gender once again neutralized: old age and waiting to die. This is the work Wilding is best known for; she was a professor of performance at SAIC. But Waiting is the only performance in the exhibit.

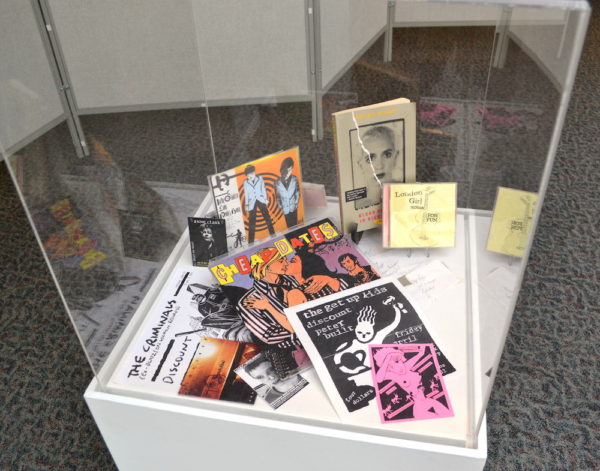

After having seen it, I still wonder how Fearful Symmetries ended up at UHCL. If there were a long tradition of showing feminist art there, I would understand. But looking at their recent previous exhibits from 2008 until now, there seems to be no such emphasis (mostly they have student and faculty exhibitions, and, for some reason, they’ve shown a lot of art from Eastern Europe). Perhaps this show signals a return to feminist art for UHCL. UHCL does have a large Women’s Studies program (begun by Calvin Cannon), and while on campus I saw another exhibit on the second floor just outside the library, Women in Punk: A Legacy of Empowerment. It was a modest show, with a folding wall displaying a large selection of punk-rock gig flyers and posters and two plexiglass cases filled with old records, books and other souvenirs of female punk rockers. It was put together by Houston artist Heather L. Johnson and David Ensminger. It was a fitting counterpart to Fearful Symmetries. Maybe this is a new beginning for feminist art exhibits at UHCL. They have an important legacy there that should be honored.

Part of the Women in Punk exhibit

Faith Wilding; Fearful Summetries at UHCL Art Gallery through December 8.

Women in Punk is on the second floor of the Bayou Building at UHCL through mid-December.