Dallas artist Giovanni Valderas has a group of objects occupying the brick shell of a building that will eventually be remodeled as part of the McKinney Avenue Contemporary’s ambitious new compound in The Cedars, south of downtown Dallas. The show is titled Forged Utopia and fits into a larger series of programming called “The New Urban Landscape” which the MAC is coordinating to address “homelessness, displacement, gentrification, and immigration,” through exhibitions, panel talks, and pop-up activities relevant to their own footprint and vision for the area. It’s a neighborhood known for both for its DIY creative art scene and its social blight. The MAC is hoping to play a role in growing this art community in ways that spill over into all segments of the neighborhood. Valderas’ work is especially pertinent to this type of growth.

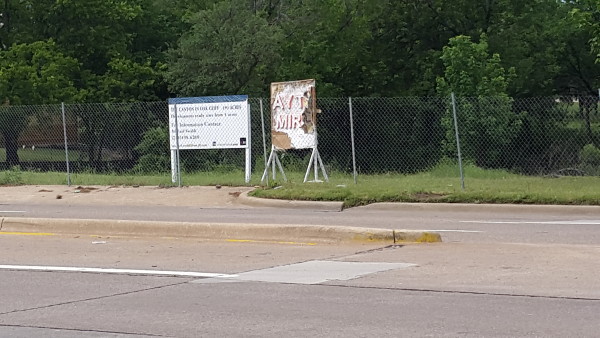

Valderas’ sculptural objects look like bright-colored piñata versions of billboard signage—the kind that advertise lots for sale—and in neighborhoods like where Valderas lives they mark changes coming from the outside in. He has mixed feelings about this kind of progress and riffs on the billboard format to try to work out what’s at stake. Instead of bland logos or digits his signs each carry a succinct expression in slangy Spanish, such as “No Hay Pedo” or “Ay Te Miro,” working-class phrases that seem to address both the local community and the hidden actors behind inevitable business transactions. They speak with humor and resignation to a culturally specific audience, one that the artist is also coaxing to consider art as an empowering activity.

In this indoor-outdoor installation the works hang from the wall or ceiling or stand up off the floor, but they’re based on a project of site-based works that Valderas has been setting up in vacant lots next to actual real-estate billboards. One has also been shown in the courtyard at Art League in Houston. The show at the MAC necessarily strips away much of their original context, and the pieces made for this space seem a bit less involved. They get the idea across though, which is what counts.

This particular type of billboard is an interesting artifact to focus on. In the wild they usually have a sterile, safe feel to them—like large-scale business cards that are just three-dimensional enough to stand up and face the road. Text, phone number, agent name: brick and mortar placards that have an intended audience, but no doubt signify something else to those living in the vicinity, whom the sign is speaking past. Valderas’ versions speak in a different language. They come plumed in extravagant color that would make an investor blush. He builds them up with wooden armatures, papier-mâché, and brightly colored fringe (materials he’s been incorporating in his work for some time now). They wield this cultural vernacular as armor in an aesthetic skirmish. There is no candy inside these boxes, and they have nothing to sell. They’re here to provoke.

The pieces work best by subverting the purpose of conventional signage, whose logic is to feed you information quickly and effortlessly, and with as little distraction as possible. Valderas’ versions are labor-intensive and intricate, with as much of their message emanating from their texture as from their text. He articulates structural details in a kind of mock celebration of their form; in some pieces he adorns the simple two-by-four bracing or recreates frilly bags of sand that hold down the sign’s feet so that it won’t blow over.

Posed next to sleek, manufactured signs, these hand-made objects feel tender and human; lavish and fleeting like nature. They recall traditional Mexican cemetery decorations. They are an offering to time and place; they break down and litter their environment with the waste of spent messages, both resisting and succumbing to the elements. With time and weather, the contrast between the two signs gets more poetic and delicious. You want to empathize with these objects—take ‘em home and patch ‘em back up.

In fact, the weightiest thing about them is the amount of love in them. And I mean “love” as measured by the labor of the hand. We have an intuitive sense for this sort of thing. It’s a value that has been collapsed and commodified, outsourced and faked. And it still matters to us; 100 hours of someone’s time, focused and made visible, is undeniably meaningful. It may seem like an absurd gesture in a way, but encountering a thoughtfully caressed object out in the world is bound to effect something congruent in the eyes and hearts that behold it.

When art tasks itself with socio-political problems, how do we evaluate it? It wants to spark some kind of change, to intervene somehow. Despite how pervasive the tactics of art are in politics and commerce, or vice-versa, the conversation of art operates on a different plane. We can stand one plane up next to the other, like Valderas does with his signs, and ape its look or function, but changing the conversation is slow and indirect. Art and life seem to speak past each other and only resemble each other superficially. But the critical muscles we build up when we engage communities in creative reflection hopefully translate to a better society, some type of “forged utopia.” We’ll be looking to the Cedars over the next few years for the signs of this.

Through June 25 at the McKinney Avenue Contemporary. Images courtesy of the artist.