Leigh Merrill’s latest.

Here’s a way to make an image unsettling: show us a human-made landscape (urban or rural, interior or exterior) and take all the humans out of it. Make a place that should be populated look deserted. Filmmakers and photographers have done this very well and for a long time. It’s creepy because you can project onto it your own reasons for its desolation, or you can learn the truth about it, which might be just as upsetting or strange as anything you’d have guessed. The ruin porn images out of Detroit, the abandoned diamond colonies of the Namibian desert captured by Doug Aitken, many of Gursky’s interiors and exteriors: these are good examples. Or, it’s an image of a setting that’s only activated when populated, so when you extract the humans you physically sense an emotional vacuum, which is also discomfiting. Misty Keasler’s Love Hotel images out of Japan are a good example of that.

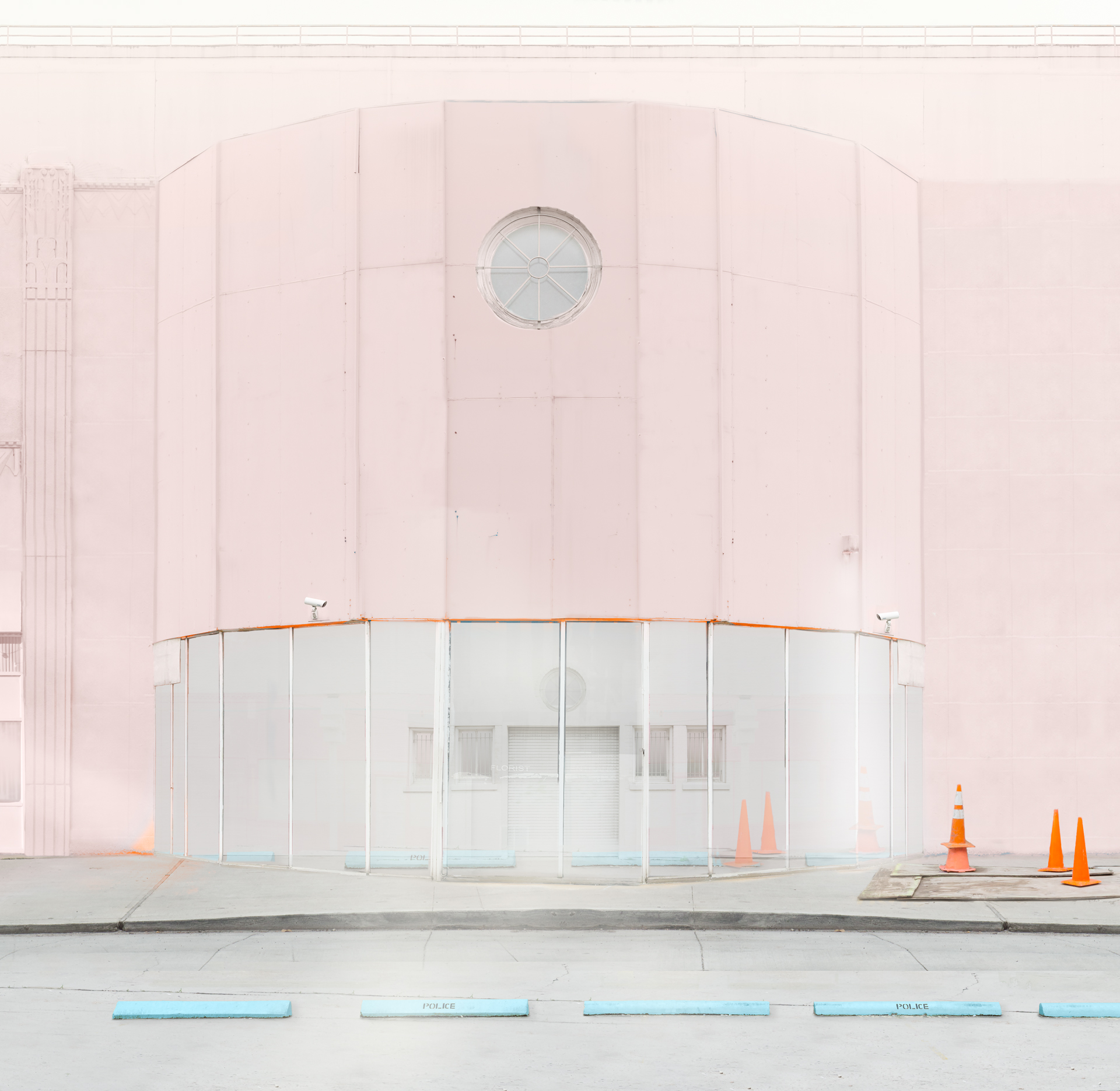

Leigh Merrill, a local artist on the upswing, has made some unsettling images lately. In her earlier work, her scenes were unpopulated, but the storefronts and parking lots from a few years ago also looked as though a group of people or cars might veer into the frame at any moment: the quietude was temporary.

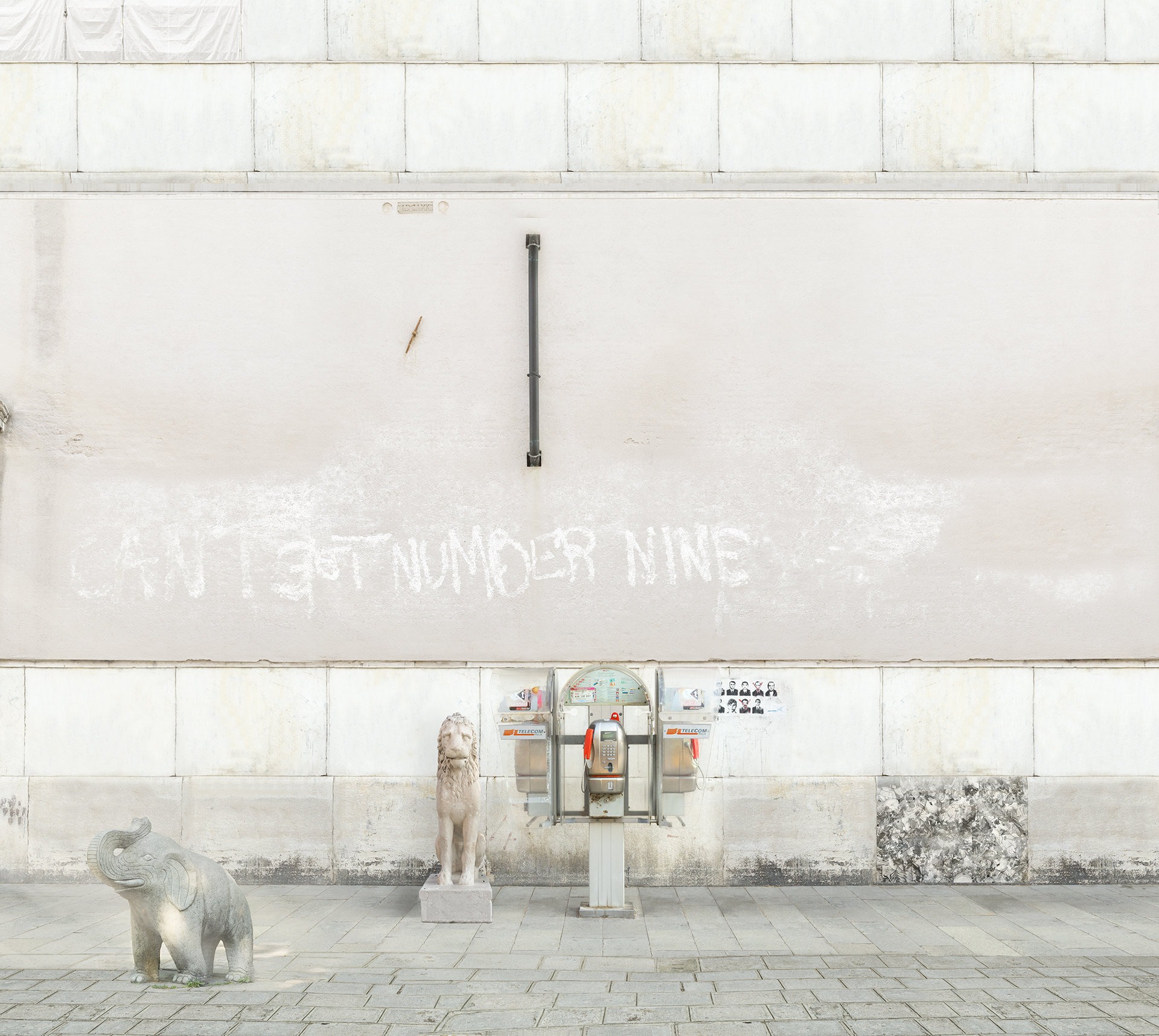

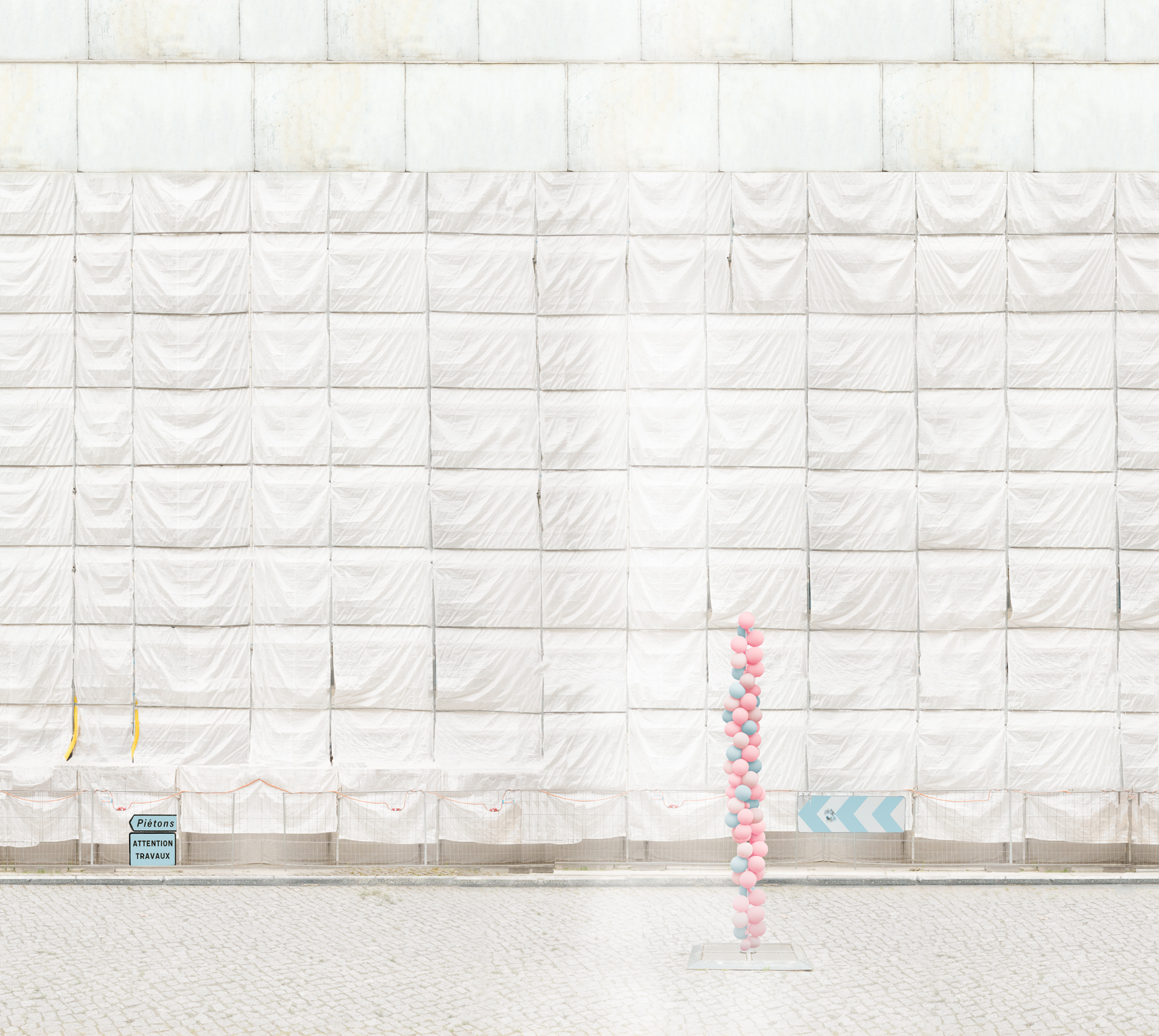

In the images on show now at Liliana Bloch’s gallery in Dallas, Merrill has traded the possibility of a scene’s re-peopled redemption for places that look as though they’re best left alone for good. And these are not straight photos she’s taken out in the world; every image is a layered aggregation of a lot of photos she’s snapped, plus her time spent in Photoshop. The places look very real, however, and just this side of recognizable. They’re washed out and humid, and pastel (like a cheap seaside resort in the Eastern Bloc). But there’s a Chernobyl-like toxicity to their atmosphere. Which is great, because the voyeur inside any viewer can look as long as they wish without having to be hosed down by the authorities afterward. I wouldn’t call her street scenes beautiful, though some might try. But (and in spite of their surface austerity), I would call them decadent, in the most literal sense.

I think her additions of recognizably surrealist touches (a marble statue; a column of balloons) to the images hurts them (while the subtler invasions don’t; I like the concrete animal sentries by the phone booth); she only oversteps in this way in a few of the works. But I think going too far with surrealness makes the uncanny turn into something pedantically gimmicky. Her real strength is in making her scenes look as though they do exist somewhere, and that she stopped to ‘take the photo’ the minute she realized she was walking through a hard and unstudied section of David Lynch’s brain. In these, we don’t need to know that she’s nuanced the scene to within an inch of its life. We can just shudder and thank our stars we’re not trapped there.

Through June 18 at Liliana Bloch Gallery, Dallas.