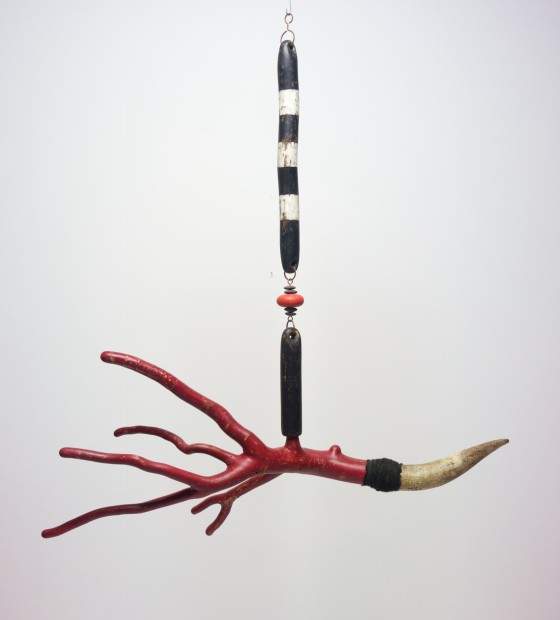

The Contentious Relic (2014-15), acrylic on wood, horn, fiber, stoneware, metal, 62″h x 52″w x 21″ d.

San Antonio sculptor Danville Chadbourne in conversation with Glasstire, in advance of Chadbourne’s solo exhibition and the unveiling of three of his acquired outdoor works at the Rockport Center for the Arts on May 14.

Glasstire: Do you remember your first exposure to art?

Danville Chadbourne: I grew up with no exposure to art at all. I was raised in Bryan, Texas. My father was an entomologist and worked in the agricultural business. I was interested in science and math, and in high school I had fantasies about writing, films and filmmaking, and book illustration. I really didn’t develop an interest or true understanding or “art” as we know it until I started college at Sam Houston State University in Huntsville.

Did you have a mentor?

Not really. But here was a great faculty at Sam Houston State, and I ended up being great friends with a lot of them. One of them was ceramicist Evelyn Anderson, and also Ken Zonker. He was a role model, in that he taught and did his work, but basically disappeared on the last day of class and traveled all over the world, backpacking and faking it, and he’d show up again the day classes started and pick up again. Evelyn and I were actually very much at odds, because she was more of a traditional ceramicist and I wanted to use clay as a sculptural material, and paint it with acrylics and attach things to it. But we ultimately became very good friends. Charles Pebworth was also an important person in my early years. He was a well-known Houston sculptor and I was his technical assistant for several years. It was indirect but I learned a lot about developing a strong work ethic from him.

Ancestral Object – A Persistence of Memory (1994-08), acrylic on wood, metal, beads, leather, 32″ h. x 15″ w.

How would you describe your work to someone who hasn’t seen it?

I suppose I would say that I make these things that are kind of like artifacts from another culture and time.

Was your style something that came to you quickly, or did it evolve?

It evolved quickly. The forms that I make now are the same kind of forms that I was making in undergraduate school, in ceramics and sculpture. I feel that my 2D work lagged behind my sculptural work. I thought the images were beautiful and the iconography was personal, but the works were too pristine, too newly made. But then two things happened: In 1975 I stopped painting for a brief period because it didn’t have the physicality that I wanted. Then, in 1976, I moved to New Mexico and started doing giant collage-like works that suggested wall fragments more than traditional paintings, very much like the painting objects that I make today.

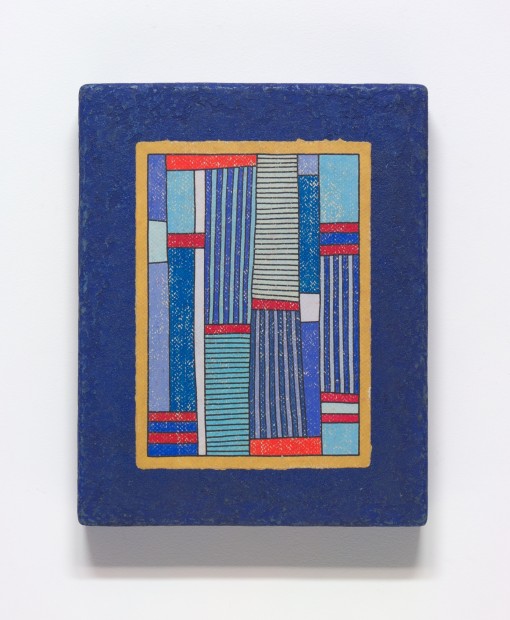

The Rhythm of Expectation – Stolen Memories (2002-15), acrylic and ink on paper, acrylic on plywood, 19″ h. x 15″ w.

Why do you think the art world is obsessed with youth and beauty over experience and maturity?

Because it’s stupid and shortsighted. The art world and art are not the same thing. The art world is the fashion world and it believes it can only sustain itself by proclaiming its newness and freshness, and it propagates the idea that only the young can provide that. It’s a myth, or a lie, but many people play this game. It is, of course, total horse shit.

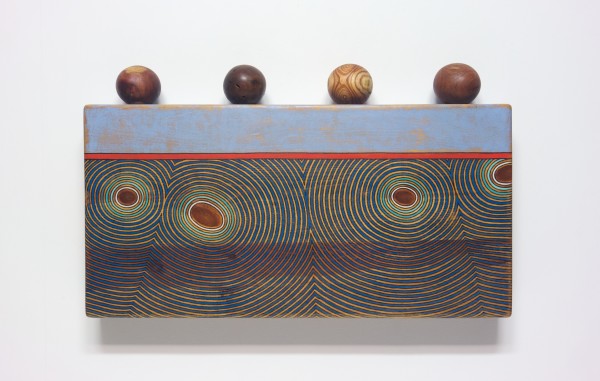

Sympathetic Beliefs – True Assumptions (2012-16) wood, ink and acrylic on wood, 20½” h. x 34″ w. x 4″ d.

In the current body of work at the Rockport Center for the Arts, are you playing with new ideas?

There are new configurations and new presentations of ideas. My work is about an expanding and evolving set of responses and interpretations of human culture. The ideas involved in that are as old as human behavior. However, there are many new works in this show, at least newly completed ones. But my work process is slow and complicated so some of the “new” works have been in process for fifteen or twenty years. New is a concept that doesn’t fit my work very well.

Your palette has changed. What is that doing to your work?

I don’t think my color palette has changed all that much in recent years. I feel it has become a wider circle, perhaps. Just like my slowly expanded range of forms. There has been some reinforcement of my color sense from recent travels in India and Peru, but the sensibility was already in place. I’ve become increasingly interested in painted historical sculpture: Greek, Egyptian, Chinese, Pre-Columbian. The use of color on these historical works is increasingly part of the conversation in contemporary archaeology and is changing some of our art historical prejudices. This information is subtly affecting my sense of how expressive color is part of human history, of human behavior. I can’t quite pin down how or why it’s affecting my work, but it’s something I’ve been looking at a lot lately.

The False Shadow of Transformation (2009-13), stoneware, stone, 78″ h. x 18″ w. x 14″ d. Recently acquired by Rockport Center for the Arts.

Your work is tribal-looking, and mysterious, and oddly comforting. Is that accurate?

Comforting. That’s not a word choice I would make, but I think I understand what you mean. There’s some aggression in them, and there’s lots of sex and death in them. Ritual activities; a lot of sexual iconography. There’s some sexual display, a sense of power, as in animal mating behaviors. It’s about life and death. Things that have had some ritual value that has now shifted. I’m interested in how human beings look at an alien piece of information, and how they interpret it. So, comforting? Sure.

Are you a spiritual person?

(Long pause): I would say… I am. Yes. My work is about the spiritual, conceptual capacity of human beings. All human beings are capable of seeing beyond their current world. I’m a total nonbeliever in the traditional sense of religious belief systems, including the ones I’m fascinated by. I’m probably more of an animist in the most basic sense. I’m fascinated by the fact that human beings have always invented this stuff for themselves.

The Calculated Risk of Incongruity (2008-14), wood, antler, metal, beads, 37″ h. x 15″ w. x 14½” d.

Would you describe your work as playful?

There are playful elements in it; bits of hidden humor, internal elements that have to do with playful relationships and parts. But no, not really. I think many people see it as playful because of the color and they live in a colorless world. But there’s also a lot of deadly serious elements in my work.

Your interests cover a spectrum of disciplines, from music and literature to the culinary arts. It seems like there’s a generation of young people who avoid well-roundedness in favor of specialization. Is that a sign of the times?

I’m not sure I completely agree that everyone is specializing, but I think that specialization has always been part of the way things work. I do feel that the academic system and the cultural concept of the job market is encouraging a narrower field of vision. I think the bigger problem is that many people don’t want to be broadly knowledgeable, that they don’t need to learn about the world around them, that they can get anything they need to know from their cell phone. That they don’t need to know anything about the physicality of the world, how to build or fix something, or where their food comes from. My tendency is to see things in a broad perspective, and my work is very much about the deep, layered history of human activity. I’m also interested in science, which I think is a big part of being generally knowledgeable.

Did you enjoy teaching?

I loved teaching. I loved the conversation in the classroom. However, I have absolutely no respect for the administration and structure of most schools today. I had some great times teaching over the seventeen years that I did it, and when you find some serious students that really care, that’s incredibly gratifying.

What’s the best advice you could give today’s art student?

Get a job. You could be a baggage handler for an airline, for example. You’re not going to make any money in the art world. Ultimately, I would say to be true to your own vision. As long as you have a vision. Otherwise you’re wasting everybody’s time.

Three works acquired by Rockport Center for the Arts, l-r: The False Shadow of Transformation (2009-13); The Inevitable Question (2007-10); The Lure of Simple Inclinations (2008-10)

If you could own any work of art, what would it be?

Stonehenge.

Your work seems to be receiving some much-deserved attention and exposure lately. Can you keep up the pace of demand?

As long as Diana can keep up with the computer crap, I can keep up with making the work. There’s plenty of finished works available. I’ve been productive over the past 40 years. I have, literally, a hundred works in process in the studio right now. And I have ten lifetimes’ worth of wood and other materials, all ready to go.

Danville Chadbourne’s solo exhibition opens at Rockport Center for the Arts on Saturday, May 14, in conjunction with the unveiling and dedication of three sculptures newly acquired by the Center. A gallery talk with the artist and the exhibition opening begin at 4:30 p.m that day. The show runs through June 11.