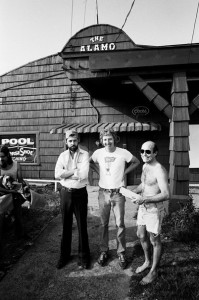

SXSW screens a newly restored indie movie shot in a Houston dive bar in 1982.

By all accounts, filmmaker Eagle Pennell was a real Texas character, in both the best and worst ways. His tenacity made him a pioneering force in the region’s independent filmmaking scene, while his ego and excesses cut short his collaborations, career breakthroughs, and eventually, his life. His double edge is the primary reason that, despite their influence locally and nationally, his films are largely unknown today. It’s hard to imagine now, but in the 1970s and early ’80s there were very few examples of movies being made outside of the established industry and away from New York or Los Angeles, and even fewer resources and outlets for independently produced, authentically regional films. Pennel’s proving that it could be done here in Texas on a shoestring budget could be considered nearly as important in establishing the homegrown flavor and independent spirit of the state’s creative communities as Willie Nelson choosing Austin over Nashville.

Born Glenn Pinnell, he changed his name in his early 20s to Eagle Pennell (the first, a nickname referencing his beak nose, and the slight spelling change of his last name referencing a character in a John Ford movie.) He attended the University of Texas in Austin but dropped out in his junior year to do film work. He made short films (the documentary Rodeo Cowboys and the narrative short A Hell of a Note), helped organize Austin’s first film festival in the mid-’70s, and in 1977 made his first feature film, The Whole Shootin’ Match. Shot on 16mm film with a local cast and way less money than would be considered a “low budget,” the lovable, low-key tragicomedy gained him attention at festivals including Dallas’ USA Film Festival and the New Directors/New Films Festival in New York. National critics Vincent Canby and Roger Ebert took note, and it had a big impact on Robert Redford, who has cited the film as a major inspiration for his starting the Sundance Institute and later the Sundance Film Festival to support regional, low-budget, independent movies.

Born Glenn Pinnell, he changed his name in his early 20s to Eagle Pennell (the first, a nickname referencing his beak nose, and the slight spelling change of his last name referencing a character in a John Ford movie.) He attended the University of Texas in Austin but dropped out in his junior year to do film work. He made short films (the documentary Rodeo Cowboys and the narrative short A Hell of a Note), helped organize Austin’s first film festival in the mid-’70s, and in 1977 made his first feature film, The Whole Shootin’ Match. Shot on 16mm film with a local cast and way less money than would be considered a “low budget,” the lovable, low-key tragicomedy gained him attention at festivals including Dallas’ USA Film Festival and the New Directors/New Films Festival in New York. National critics Vincent Canby and Roger Ebert took note, and it had a big impact on Robert Redford, who has cited the film as a major inspiration for his starting the Sundance Institute and later the Sundance Film Festival to support regional, low-budget, independent movies.

Pennell moved to Houston in the early 1980s, and with the help of a modest NEA grant and in-kind support from Southwest Alternate Media Project (SWAMP), he directed his second feature film. A collaboration with writer Kim Henkel (who’d written The Texas Chainsaw Massacre), Last Night at the Alamo was filmed in the summer of 1982 and completed in ’83. The film was well received, winning a Special Jury Prize at Sundance (in its inaugural year) and called an “all-American classic” by New York Times critic Canby, who drew comparisons to the work of Sam Shepard, David Mamet, and Eugene O’Neill. The film opened some doors for Pennell to work in Hollywood, though those opportunities were apparently squandered quickly by his spiraling alcoholism. Despite having a leg up on the coming explosion of “independent film” (the first efforts of Jim Jarmusch and the Coen Brothers would be seen the following year, and those of younger Texas filmmakers Linklater, Rodriguez, and Anderson nearly a decade later), Pennell never built upon the promise of his first two movies and so remained a tangential, early catalyst rather than a leading figure.

Pennell moved to Houston in the early 1980s, and with the help of a modest NEA grant and in-kind support from Southwest Alternate Media Project (SWAMP), he directed his second feature film. A collaboration with writer Kim Henkel (who’d written The Texas Chainsaw Massacre), Last Night at the Alamo was filmed in the summer of 1982 and completed in ’83. The film was well received, winning a Special Jury Prize at Sundance (in its inaugural year) and called an “all-American classic” by New York Times critic Canby, who drew comparisons to the work of Sam Shepard, David Mamet, and Eugene O’Neill. The film opened some doors for Pennell to work in Hollywood, though those opportunities were apparently squandered quickly by his spiraling alcoholism. Despite having a leg up on the coming explosion of “independent film” (the first efforts of Jim Jarmusch and the Coen Brothers would be seen the following year, and those of younger Texas filmmakers Linklater, Rodriguez, and Anderson nearly a decade later), Pennell never built upon the promise of his first two movies and so remained a tangential, early catalyst rather than a leading figure.

Over the past decade, Louis Black (co-founder of SXSW and the Austin Chronicle) and Mark Rance (Watchmaker Films) have been working together to restore and reintroduce a number of Texas-made films that have gone unseen for too long. Among the unique, lost treasures unearthed by their efforts is Tobe Hopper’s first feature Eggshells, Brian Hansen’s Speed Of Light, and David Boone’s Invasion of the Aluminum People. The first of their restoration projects in 2006 was Eagle Pennell’s debut feature, The Whole Shootin’ Match. Their most recent project, which will premiere at the upcoming SXSW fest, is a restoration of Pennell’s second feature, Last Night at the Alamo. These special screenings are great opportunities to revisit the local rarity at its best (in crisp black-and-white on the big screen) and in the presence of some folks involved in the original production (including writer Kim Henkel, actor Sonny Carl Davis, cinematographer Brian Huberman, musician and Eagle’s brother Chuck Pinnell). The film will go on to special screenings in Houston, Los Angeles and elsewhere in the coming months, and be an eventual video release through the University of Texas Press.

It’s interesting to see Last Night at the Alamo now—its authentic regionality given the added temporal region of 33 years ago. Aside from a brief opening montage of city buildings, traffic, and street signs (which will be of particular interest to Houstonians), the film takes place entirely in and around a dive bar called the Alamo on the eve of its demolition. Regulars have gathered there for one last night of 50-cent Lone Stars, lazy pool games, bitching, bragging, and brawling before their dingy refuge closes its doors for good and disappears. Unmistakably Texan accents and colloquialisms—including near constant ornamental profanity—are so rarely heard in movies that it seems as novel as a bar with no TV screens or cell phones in it. But before one settles too comfortably into nostalgia, the film’s charms blur with beer into bleaker complexities. Overt, near abusive male chauvinism, macho bravado, and juvenile fantasies begin to reveal a mess of issues with these lost manchildren.

It’s interesting to see Last Night at the Alamo now—its authentic regionality given the added temporal region of 33 years ago. Aside from a brief opening montage of city buildings, traffic, and street signs (which will be of particular interest to Houstonians), the film takes place entirely in and around a dive bar called the Alamo on the eve of its demolition. Regulars have gathered there for one last night of 50-cent Lone Stars, lazy pool games, bitching, bragging, and brawling before their dingy refuge closes its doors for good and disappears. Unmistakably Texan accents and colloquialisms—including near constant ornamental profanity—are so rarely heard in movies that it seems as novel as a bar with no TV screens or cell phones in it. But before one settles too comfortably into nostalgia, the film’s charms blur with beer into bleaker complexities. Overt, near abusive male chauvinism, macho bravado, and juvenile fantasies begin to reveal a mess of issues with these lost manchildren.

Couched inside a hybrid of Texas metaphors for defeat (the battle of the Alamo/the unstoppable force of urban commercial development), the film seems to me to be a sort of wake for the “good ol’ boy,” simultaneously celebrating, condemning, and shrugging at male dysfunction and alcoholism. The fact that it does this with a sense of humor and a resignation to having no real epiphanies is perhaps its real authenticity, beyond simply reflecting its time and place. There’s a psychological suspension here that is completely unique to this particular cinematic blues. By subtle turns light and heavy, funny and ugly, exciting and boring, the unsentimental Last Night at the Alamo keeps us inside this little world til last call. Or til the whole thing gets paved over—whichever comes first.

Couched inside a hybrid of Texas metaphors for defeat (the battle of the Alamo/the unstoppable force of urban commercial development), the film seems to me to be a sort of wake for the “good ol’ boy,” simultaneously celebrating, condemning, and shrugging at male dysfunction and alcoholism. The fact that it does this with a sense of humor and a resignation to having no real epiphanies is perhaps its real authenticity, beyond simply reflecting its time and place. There’s a psychological suspension here that is completely unique to this particular cinematic blues. By subtle turns light and heavy, funny and ugly, exciting and boring, the unsentimental Last Night at the Alamo keeps us inside this little world til last call. Or til the whole thing gets paved over—whichever comes first.

The newly restored Last Night of the Alamo (1983) screens as part of SXSW on Monday, March 14, Wednesday, March 16, and Friday, March 18. More info HERE.

1 comment

http://www.brianhuberman.com/2016/04/09/notes-alamo-survivor/