A relative newcomer to the San Antonio art scene, Fernando Andrade is one of five artists who make up the inaugural class of the Guadalupe Cultural Art Center’s Artist Lab program. Now in the second year of its first cycle, the program pairs local artists with internationally known artists and curators who provide mentorship in the areas of artistic and business development. When entering the program, Andrade had already received critical praise for finely executed drawings that use a soft and eloquent voice to call attention to the violent activities of drug cartels along the U.S.-Mexico border. His newer works, which respond in part to his interactions with mentors and the other Artist Lab participants, reveal a broadening of his repertoire of mediums, which now includes drawing, printmaking, sculpture, and installation.

A native of Acuña, Mexico (located six miles south of Del Rio, Texas), Andrade moved to San Antonio with his family in 1994, at the age of seven. A 2008 graduate of the Graphic Design program at San Antonio College, Andrade worked on neighborhood mural projects in 2007-08 and has been exhibiting locally in group shows since 2006. In the past two years, he’s had solo exhibitions at San Antonio’s Hausmann Millworks and Blue Star Contemporary Art Museum.

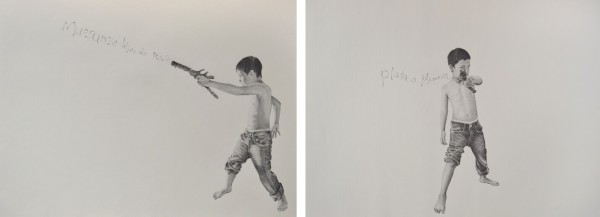

Mueranze Hijos de Puta (Die Sons of Bitches), 2013, graphite on paper, 18 x 24 in;

Plata O Plomo (Silver or Lead)?, 2013, graphite on paper, 18 x 24 in.

In his debut solo exhibition at the Hausmann Millworks, Andrade presented a handsome suite of drawings under the heading “A Jugar la Guerrita (To Play a Little War).” In each drawing, a young Mexican boy is shown amidst a barren background in carefully staged action poses that suggest he is playing a child’s war game, with a tree branch serving as a surrogate gun or a rock acting as a stand-in grenade. Although the imagery seems innocent at first, hand-drawn text spewing from the branches simulates smoke from a rifle and provides references to the underlying meaning of the scenarios. In one example, the boy aims a “gun” that fires the phrase “mueranze hijos de puta,” which in Spanish slang roughly translates as “die sons of bitches,” the typical language of drug cartel members that permeates the air where children play just south of the border. In another, a “gun” pointed at the viewer emits the words “plata o plomo,” which means “silver or lead” and refers to money or bullets, which are commonly demanded by cartel members as they rob their victims or force them to pay for protection of their homes or businesses. So these children are not so naive after all. In contrast to the artist’s more peaceful years earlier in the region, today this violence is prominent.

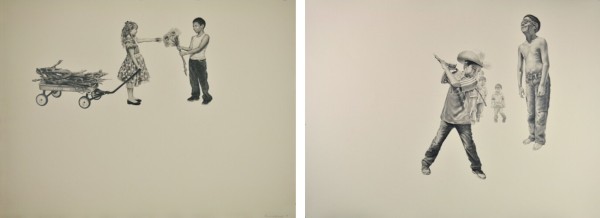

Intercambio (Exchange), 2014, graphite on wheat tone paper, 22 x 30 in.

La Piñata, 2014, graphite on wheat tone paper, 22 x 30 in.

The issue became particularly emotional for the the artist when, in 2012, he learned that a friend went missing, never again to be seen. While grieving over the disappearance of this friend, Andrade took to researching the current state of border violence by seeking out more stories from friends and relatives and studying news reports, books, and online media. As a way of making his findings public, he expanded the scope of his narrative in the drawing series Tierra y Libertad (Land and Liberty), which comprised his solo show at Blue Star Contemporary Art Museum in 2014.

The dramas in this series involve groupings of children who, once again, appear to be playing games. Only this time they’re engaged in a range of activities that mimic the crimes of the drug lords. In Intercambio (Exchange), a young boy offering a floral bouquet to a little girl pulling a wagonload of stacked branches refers to the exchange of guns for drugs. In La Piñata, a traditional Mexican birthday celebration is a symbolic enactment of a beating or a lynching. In another drawing, a boy stirs liquid in a barrel with a human arm draped over its front, a reference to the gruesome practice of body disposal by acid bath. And in another, two boys tug at a filled garbage bag, a symbolic surrogate for a body bag.

The latter scene, in fact, provided the concept for Andrade’s first venture into installation art, which he presented earlier this year as his initial project for the Artist Lab at the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center. The artist’s most emotionally charged work to date, Estudios de un cuerpo humano (Studies of a Human Body) consists of five folded trash bags spread laterally across the softly lit wall of a darkened chamber, with each bag serving as the drawing surface for images of amputated body parts and, on the centrally positioned bag, a pair of shoes. With the white oil pastel of the drawing contrasting starkly with the black of the plastic, the installation is succinct and compelling in its expression of deep tragedy and loss.

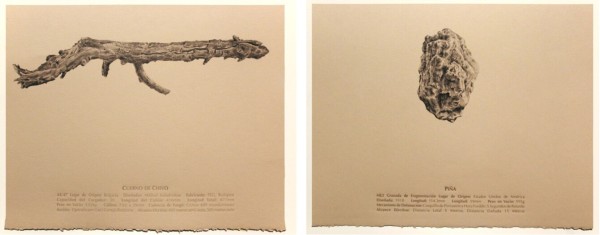

Cuerno de Chivo (Goat’s Horn), 2013, graphite and embossed text on Canson wheat paper, 11 x 14 in. Piña (Pineapple), 2013, graphite and embossed text on Canson wheat paper, 11 x 14 in.

In addition to investigating his subject through figurative narratives, Andrade uses a more conceptual emblematic format in mixed media drawings, prints and sculptures that focus specifically on the topic of guns and grenades. In the series Palos y Piedras (Sticks and Stones), produced in collaboration with Hare & Hound Press and introduced in a recent show at San Antonio’s Cinnabar Gallery, Andrade isolates solitary objects, finely drawn in graphite, in the upper center of a composition such that each image appears to float. Rendered with meticulous hyperrealist detail, the objects seem magnified as if they’re specimens under observation in a laboratory, an effect that’s reinforced by the embossing of statistical text below them. Text and titles are particularly relevant here, because they clue us in to Andrade’s interest in the objects. The title for a drawing of a branch, Cuerno de Chivo (Goat’s Horn), is actually Mexican slang for the curved magazine clip of an AK-47 rifle. Piña (Pineapple), the title for a drawing of a rock, is similarly slang for an MK-2 grenade. In the accompanying texts, Andrade identifies each of the objects as weapons, and offers the kind of statistical information (in Spanish) that one might find in a catalog or on a museum label. Through inviting us to recognize the differences between what each object appears to represent and what printed words tell us it it symbolizes, Andrade encourages us to reflect upon the connection between weapons and acts of violence.

Made in Texas by Texans, 2015, graphite and debossed text on wheat toned paper, 18 x 24 in.

Two Shots Ten Hits, 2015, graphite and debossed text on wheat toned paper, 18 x 24 in.

With open carry laws recently implemented in Texas, Andrade’s newest body of work could not be more timely. An extension of Palos y Piedras, the God Bless America series continues the exploration of branches as surrogates for guns, but is made up of drawings with debossed text and sculptures cast from found branches chosen specifically for their resemblance to the subject. In the drawings, Andrade reveals his background in graphic design, as his research for the project involved combing through gun advertisements in magazines from the 1950s to the present. In each example, a slogan appropriated from a gun ad is printed in faint stamped text, superimposed over a beautifully drawn, crisp and highly textured image of a branch. While the idea for debossing directly over the image was inspired by the way brand logos are imprinted on a gun’s surface, the text in Andrade’s drawings remains partially obscured, which creates a dynamic tension between image and text as both compete for our attention.

M1 Garand Semi Auto Rifle, 2015, plastic, graphite powder, 8 x 24 x 1 1/2 in.

Flintlock Pistol, 2015, plastic, graphite powder, 5 x 16 x 1 1/2 in.

In the new sculptures, Andrade relies more on our purely visceral responses to engage us in thinking about the connections between guns and violence. Although titles still clue us in to the artist’s intended symbolism, it is the ambiguities existent in what the objects seem to represent, along with the aesthetic temperament of their fragile brittle surfaces, that instill metaphoric thinking not only about guns, but about human vulnerability and the preciousness of life itself. Created by plastic casting the branches and then saturating the casts with graphite powder, these objects make maximum impact when seen up close and in person. (Some are on view at the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center through February 16.) With their velvety metallic surfaces, works like M1 Garand Semi Auto Rifle appeal to our idea of touch; we want to pick them up. Flintlock Pistol, on the other hand, is shaped like a limp, prone body. In addition to symbolizing a gun, it’s a haunting metaphor for the gun’s victim.

1 comment

Rubin is always really supportive of young, Latino male artists. Keep it up David!