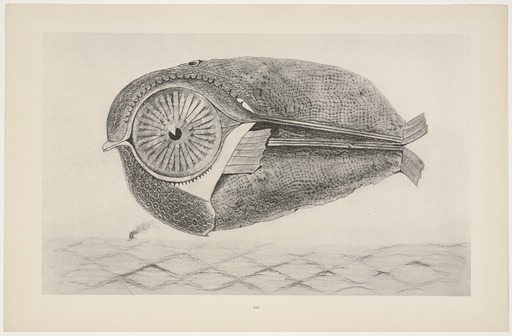

Max Ernst, L’évadé (The Fugitive), 1925. Collotype on paper from a 1925 black crayon frottage, with gouache on paper.

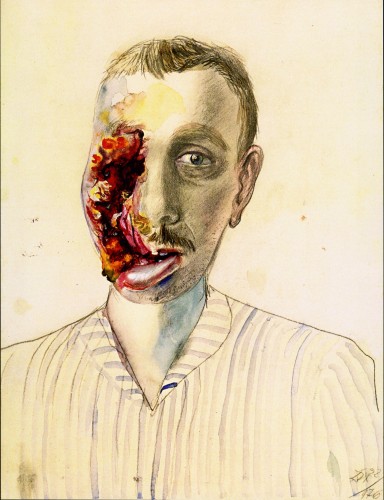

Artists never forget their first loves, the works or artists who first mark them in a permanent way. For me, as an undergraduate painter, it was the work of the German Expressionist painters of the Weimar era—often grouped together under the label New Objectivity—that changed my understanding of the power of art images.

These artists grappled directly with the shock and alienation that rippled across the globe after World War I. The horrific disfigurement of humanity and its fragile morality were depicted in unsparingly graphic, blackly humorous, always seductive imagery. In many ways German Expressionism created the modern horror genre in art, literature and film.

If the German Expressionists like Otto Dix and George Grosz faced this new, brutal objectivity with eyes wide open, their French counterparts such as Andre Breton and Max Ernst threw themselves into a Surrealist world with their eyes tightly shut.

The archaic, idealized world of French Surrealism is a seductive landscape to explore, but like all narcotics, an addiction to it can be deadly. You might never see the real world again. So I’ve been concerned lately, as both my drawings and my writing have begun to exhibit strong signs of Surrealism’s hallmark infatuation with a loose, mostly gentle rendering of the unconscious.

Sometimes I slip into love with ideas and push them to their breaking point. Most artists move through obsessive cycles in which we wrap our thoughts too tightly around an idea and suddenly find ourselves in a place we never intended to go and might not mean to stay.

So I ventured to The Menil in Houston to see Max Ernst’s frottage drawings in the excellent exhibition Apparitions: Frottages and Rubbings from 1860 to Now, curated by Allegra Pesenti. I wanted to get to the bottom of this unexpected shift in my thinking and since drawing is how I understand the world best, I wanted to see what Ernst could tell me about my discomfort with my current mindset through his automatic drawings.

Max Ernst, Le Start du Chataignier (The Start of the Chestnut Tree) 1925. Collotype on paper from a black crayon frottage, with gouache on paper. From Histoire Naturelle, published by Galerie Jeanne Bucher, Paris, 1926.

As I stood in front of the large wall of collotypes of Ernst’s frottages and the smaller wall of original drawings by him, Andre Breton and others, I recognized that as drawings they are subtle and evocative, with a line that shows true refinement and sensitivity. They are, in a word, beautiful.

And it’s easy to stay there in the beauty, exploring the primordial worlds that emerge by gently touching the earth with paper and pencil and then, through the artist’s unconscious, coaxing a hidden, magical world out of those impressions.

But art does not exist outside of its historical context in a living way. To admire Ernst’s drawings as beautiful and mysterious but not to remember that Europe was criss-crossed by barbed wire and trenches full of flesh and bone is to absolve them of their responsibilities as living art. This is easy to do because we are taught that museums are mausoleums.

Every country in the world felt the effects of World War I. It left 17 million people dead in trenches and 20 million more physically and psychologically broken. The human race had experienced its first truly global war.

The Ernst drawings on view open in 1925. The most devastating, mechanized war in human history had gone into hibernation seven years earlier and in that same year Adolph Hitler published Mein Kampf. Two years before, Otto Dix painted his horrifying picture The Trench.

The world I saw in the Ernst frottages at The Menil is a mystical world. Any uneasiness in it seems like a primal fatality. They are a Histoire Naturelle world of little tables, docile lime trees and Rivers of Love.

I left the exhibition understanding again why I have distrusted Surrealism from the beginning of my interest in art history. It has always felt too much like the religious retreat from pain and hardship to an idealized reality of my childhood.

The human impulse that brought French Surrealist art into the world was not, contrary to what Breton claims in the Surrealist Manifesto, one of “complete nonconformism.” Surrealism was a retreat into the mystical shelter of idealization and dreams. Breton says as much in the final line of the Manifesto when he writes, “Existence is elsewhere.”

Otto Dix, Triptychon Der Krieg (War Triptych), 1929-32. Tempera on wood. Gemäldegalerie Neue Meister, Dresden.

In their dogged pursuit of the most brutal truths of modern civilization, the German Expressionists tell us that when we believe existence is elsewhere, we give ourselves free rein to forget, destroy and dehumanize here, now, in the present. If we wish to breathe real life into the art we love and study we have to place it in its time and hold it responsible to the pursuit of freedom within the era in which it was born. So I’m going to leave Max Ernst behind in his delicate landscapes and return to the trenches with Otto Dix.

‘Apparitions: Frottages and Rubbings from 1860 to Now’ through Jan. 3, 2016 at The Menil Collection, Houston.

2 comments

It’s interesting to think that the brutal realism came mostly out of Germany, the invader; and the etherial escapism came mostly out of France, the invaded (thinking forward to WWII)… perhaps French artists had so fully absorbed their own country’s forays into nasty, ill-conceived expansion from a century prior that to acknowledge the ugliness was somehow impossible? I wonder if there has been/will be a similar, century-on effect happening in Germany as we close in on the centennial of WWI and plunge towards that of WWII…

says the one using charcoal