The Coming Herd–Morning, undated, pastel on cardboard, 12 3/16 x 24 inches. Image courtesy of the Harry Ransom Center

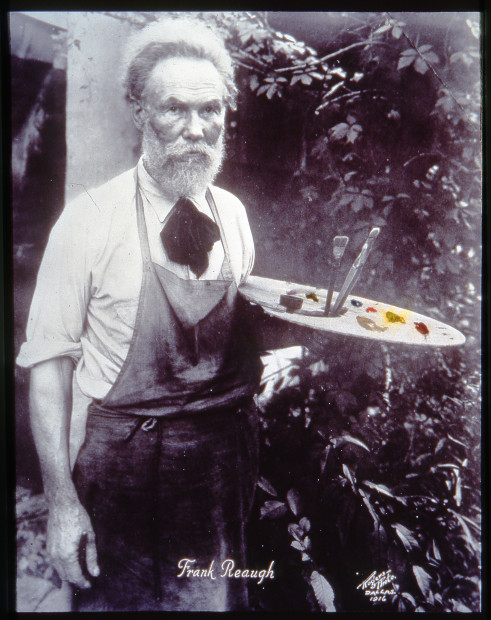

At some point in his long, productive life the artist Frank Reaugh (1860-1945) appraised his youthful self as “the most awkward fellow you ever saw.” A 1924 photograph of Reaugh (pronounced “Ray”) standing with art students beside the open-air Model T that he named the “Cicada” indicates that as a senior artist, he was something of a maverick as well, his stance an oddity of angles as his thick shock of hair and brushy goatee flap and bend in the wind.

Undated photo of Frank Reaugh and students with truck, Cicada. Unknown photographer. Image courtesy of Jerry Bywaters Collection on Art of the Southwest, Bywaters Special Collections, Hamon Arts Library, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas.

The image is one of hundreds of artifacts and artworks in the exhibition Frank Reaugh: Landscapes of Texas and the American West on view through November 29 at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas in Austin. The most comprehensive presentation of the artist’s life and work ever assembled, the show tracks, through titled galleries, Reaugh’s development and career from his early influences and artistic efforts to his own influence on other artists, and his bold and dramatic later years.

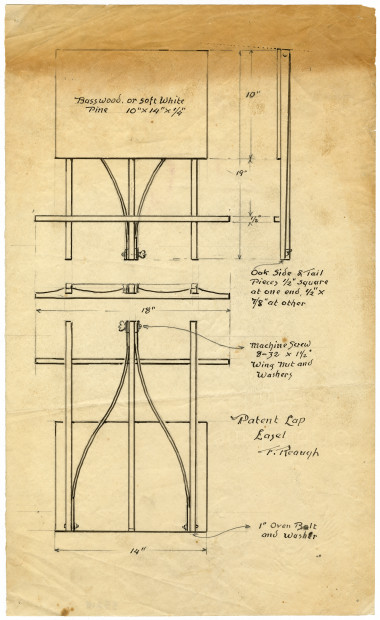

Sometimes referred to as “the Dean of Texas Artists,” Reaugh’s primary legacy involves his combination of European Impressionism with his singular style of en plein air (outdoor) painting. The show highlights his distinctively atmospheric pastels of Western scenes, many featuring the vast open plains, but also reveals that the artist was a remarkable inventor, creating and marketing his own lap easel and secret-ingredients pastel sticks, among other innovations.

Autumn Sun, circa 1883, pastel on paper, 4 3/8 x 9 1/16 inches. Image courtesy of the Harry Ransom Center

Charles Franklin Reaugh moved to Texas from Illinois in 1876, traveling with his family in a covered wagon. They settled first near Terrell, in Kaufman County, where the inquisitive teen began studying the physicality of Longhorns and other cattle breeds. Small monochrome pastels in the exhibition, most dated 1880-1885, exemplify this early period when his artistic reference was limited to engravings and photo reproductions. Arkansas River (undated; pastel on paper) captures a scene of ribboned moonlight that arcs skyward and falls across the water.

Reaugh cited etchings by the Dutch artist Paulus Potter as an influence, and the exhibition includes Potter’s 1650 etching The Bull, from the Series of Various Oxen and Cows. At age 21, Reaugh traveled to St. Louis, Canada, and New York, experiencing original paintings on the trip for the first time in his life. Influences on view also include the 1886 oil painting Indian Canoe by Albert Bierstadt, a romantic scene drenched with oozing, buttery sunlight. Regarding that specific influence, Reaugh seems to have toned down such romanticism in his own work, presenting landscapes that were all the more compelling for their subtlety and restraint.

Before the Reaughs moved to the Oak Cliff neighborhood of Dallas in 1890, Reaugh made the first of his western sketch trips, on a cattle roundup near Wichita Falls; acquired formal art training at the St. Louis School and Museum of Fine Arts; taught art classes in Terrell; attended L’Académie Julian in Paris, where he saw pastels at the Louvre; made a West Texas sketch trip in a Studebaker hack; and began exhibiting his work at the Texas State Fair and Dallas Exposition.

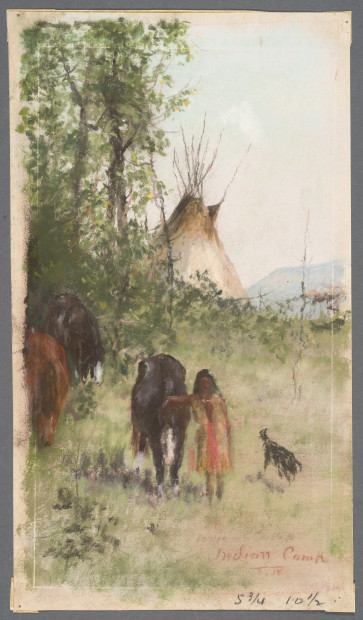

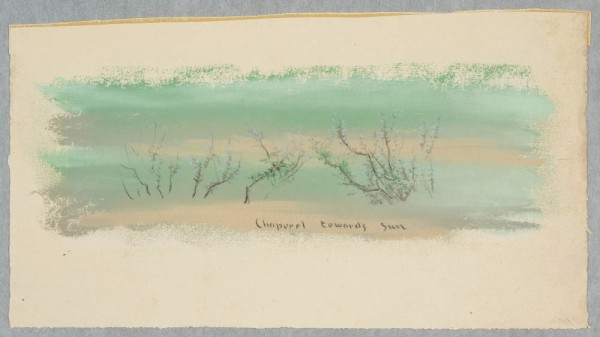

A gallery of small sketches and studies at the Ransom Center contains Reaugh’s captivating miniatures of landscapes, animal studies, Indian camps, and flora. The bluish-green abstract field with spiny brush of the pastel Chaparral towards Sun works against type with its absence of blaring light. “[The use of pastels] makes for speed,” wrote Reaugh, “the great essential in landscape sketching where effects are fleeting.”

Indian Camp, circa 1883, pastel on paper, 11 13/16 x 6 11/16 inches. Image courtesy of the Harry Ransom Center

A large gallery titled MOUNTAINS, CANYONS, LAKES, AND RIVERS contains a rich selection of Reaugh’s larger pastels and oil paintings created during a half-century of sketch trips throughout West Texas and to other western states. Artifacts on display offer details on the trips, which were conducted on horseback and by mule team and covered wagon, buckboard, automobile, and train. Students were allowed to bring 30 pounds of gear, including a blanket, an easel and an umbrella, but “cots and fancy camp arrangements are not recommended.”

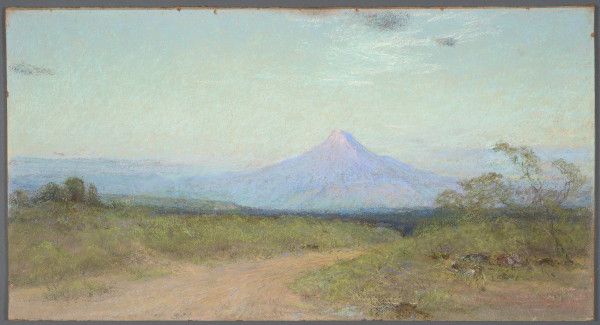

“The Rockies are fine, but I like Texas better,” Reaugh told the Dallas Times Herald after a 1933 trip. “Forms [in Texas] are more interesting, and color is as varied and more harmonious.” The trips could be pretty rugged affairs, and Reaugh’s handwritten accounts indicate that women and girls were often hardier road artists than the men. Insatiably curious about the world around him, Reaugh lectured sketch-trip students on the history, geology, paleontology, and archeology of visited sites.

Prophet’s Ford, undated, pastel on cardboard, 16 15/16 x 31 7/8 inches. Image courtesy of the Harry Ransom Center

Works in the gallery present some of Reaugh’s favorite Texas locations, including Margaret’s Peak (Coke County, named for a girl who was killed and buried on the peak by Indians), McAdams Peak (Palo Pinto County), Tule Canyon (Briscoe County), and the Brazos River. A blue haze shimmers in what Reaugh called the “illimitable distance” of the plains, and rock strata show brilliant yet subtle coloration on cliffs and canyon walls. Longhorns drink from the Brazos in Prophet’s Ford as wispy mesquites seem to cry out for water in territory that appears untouched by man. In Lightning (undated; pastel on paper) the shaft of electric energy is blinding white on the darkened, stormy ranch landscape.

Margaret’s Peak, circa 1933, pastel on Masonite, 16 1/8 x 29 15/16 inches. Image courtesy of the Harry Ransom Center

Letters, tickets, and other artifacts document the exhibition of Reaugh works at Chicago’s 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition and the Louisiana Purchase Exposition held in St. Louis in 1904. And a gallery titled THE DEAN OF TEXAS ARTISTS features work by Alexandre Hogue, Lucretia Donnell Coke, Josephine Oliver Travis, Reveau Mott Bassett, Perry Nichols, and other Reaugh students. Display case ephemera includes the 1925-26 Frank Reaugh Art Club yearbook (the club continues in Dallas today); an undated program for a lecture, exhibition, and concert held at Reaugh’s Oak Cliff studio, which was called El Sibil; and a 1918 Dallas Daily Times Herald article about Reaugh’s Strignian Club, a club for young girls who studied life drawing, took nature walks, and learned about plant and animal identification.

The gallery also includes A Mexican Longhorn by Frederic Remington and several small bronzes by Charles M. Russell, both marquee Western artists of Reaugh’s era. Which doesn’t necessarily mean that the Dallas-based artist was impressed. “Remington knew little about cows,” the man who spent decades examining the body language of Longhorns famously observed, “and was principally interested in the cowboy as a wild man.”

An open space gallery titled REAUGH’S RENAISSANCE shows artifacts and images related to the artist’s studio—including an undated photograph and architectural sketch of Reaugh’s studio, designed in a Spanish colonial revival style—along with patent applications, designs, and other memorabilia related to his Limacon fire pump, his cooling mechanism for explosive engines, and his innovations in picture-frame moldings.

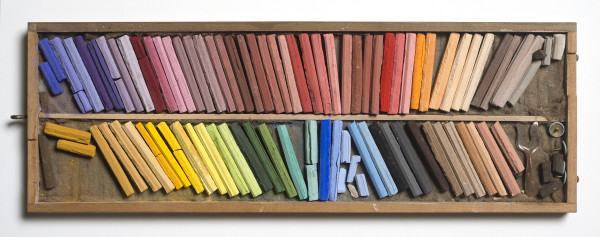

Austin artist Lucretia Donnell Coke, whose artist mother first took her on a Reaugh sketch trip at age six and who is currently a few seasons shy of the century mark, lent the exhibition a Frank Reaugh patented lap easel. A box of Reaugh pastels still retains its original wrapper with the artist’s detailed instructions on opening the box and the admonition to the novice that he or she memorize them.

“Mrs. Coke gave me a Frank Reaugh pastel lesson,” says exhibition curator Peter Mears. “She showed me how they framed what they wanted to paint beforehand. Then they would sketch the scene in pencil and fill it in with the pastels, always working from the top down. She explained that Mr. Reaugh formulated his pastels to be somewhat hard. The paper he created had a silica sand wash—it was like sandpaper, and the silica particles would pick up and hold the pastels. And when he worked with Masonite, he used the coarse side of the board because it would also grab and hold the pastel.”

Frank Reaugh’s box of pastels, with custom pastels color-keyed to native flora. Photo by Pete Smith. Image courtesy of the Harry Ransom Center

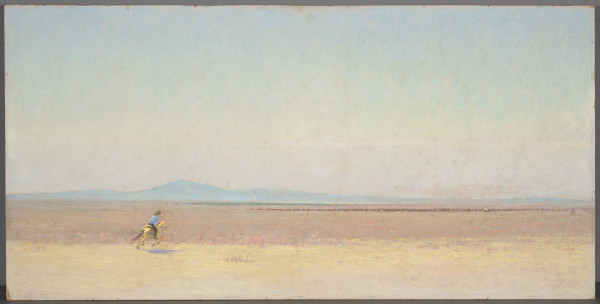

The final gallery of the exhibition, TWENTY-FOUR HOURS WITH THE HERD, holds a series of seven large pastels that Reaugh created late in his career, many of them based on works developed decades earlier. As the title suggests, the seven works follow one day and night in the life of a cattle drive, as the animals are driven, watered, bedded, and guarded. In the fifth work, cattle stampede through a canyon by moonlight. Dawn first begins to break in the sixth, and the herd is somewhat settled. In the concluding image, The Herd Moves On, a tiny line of cattle recedes across the plain, a hazy blue mountain in the distance.

The Herd Moves On, Number 7 from Twenty-four Hours with the Herd, 1932, pastel on Masonite, 24 x 48 1/16 inches. Image courtesy of the Harry Ransom Center

Reaugh presented the works, which served as something of a retrospective, in a public performance of the same name that premiered in the Highland Park section of Dallas in 1933. An early form of Texas performance art, the event featured musical interludes by pianist and composer David Guion, including his own compositions and his arrangements of Western songs like “Home on the Range”—tunes that were still somewhat novel in pop culture as a new breed of performers called singing cowboys introduced them on radio and in “talkie” motion pictures. And, collaborating with Western author Clyde Walton Hill for the performance, Reaugh composed a prose narrative for each artwork, which was read by a narrator after each pastel was placed on an easel by invisible hands reaching from behind a black velvet drape. Memorabilia in the exhibition includes an original 1933 program and Guion’s handwritten “Home on the Range” arrangement. Twenty-four Hours with the Herd was repeated at Baylor University in 1935 and back in Dallas at the Texas Centennial Exposition in 1936. The following year, when Reaugh donated a significant portion of his work to the University of Texas at Austin, the performance was staged in UT’s student union building.*

Undated portrait of Frank Reaugh with palette. Unknown photographer. Image courtesy of the Harry Ransom Center

“I like to sleep under the stars far away on the western prairie,” Reaugh wrote in a small booklet, Biographical, in 1936, “far away from the telephone bell and the railway whistle, far away from man and his civilization… . I like the opalescent color of the plains… . The steer and the cowboy are gone. The range has been fenced and plowed, and the beauty of the early days is but a memory.”

Through November 29 at the Harry Ransom Center, UT Austin.

Note: On October 1, the Harry Ransom Center will host a panel discussion and book signing featuring several of the contributors to the exhibition’s luscious, thick catalog, ‘Windows on the West: The Art of Frank Reaugh,’ edited by Peter F. Mears.

*On November 13, the Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum will present two performances (7:15 and 9:30 p.m.) of Frank Reaugh’s ‘Twenty-four Hours with the Herd,’ featuring music by Graham Reynolds with Redd Volkaert, in the museum’s Texas Spirit Theater, where Reaugh’s pastels will be projected on the theater’s massive screens.

Author’s note: I like to think of Reaugh’s sketching treks as trails blazed for programs like Land Arts of the American West at the University of New Mexico and Texas Tech State University, “a semester long transdisciplinary field program expanding the definition of land art through direct experience with the full range of human interventions in the landscape, from the inscriptions of pictographs and petrogylphs to the construction of roads, dwellings, and monuments, as well as traces of those actions.” See Land Arts of the American West by Bill Gilbert and Chris Taylor (UT Press, 2009) and landarts.org.

1 comment

See the Bryan Museum’s Facebook page for images of some Reaugh artifacts on view there. They lent several things to the Ransom exhibition, as did the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum and other institutions. From the Bryan Museum FB page: Collection Highlight – The Charles Franklin “Frank” Reaugh Collection: Artist Frank Reaugh, one of Mr. Bryan’s favorite artists, is known for his pastel landscapes and “portraits” of the longhorn cattle that once freely roamed Texas. With a group of students, each of whom became well-known artists in their own right, Reaugh took months-long sketch trips into the Texas Hill Country and Big Bend region. The Reaugh Collection includes Reaugh’s business papers, letters, books, sketchbooks, photographs, exhibition catalogs, newspaper articles, and works of art. Reaugh was also an inventor, and we are proud to have the exquisite writing desk he created out of a piano. Open from Friday to Monday – 11AM to 4PM