For her latest exhibition, I was really gonna be something at the age of twenty-three, at Microscope Gallery in Brooklyn, Houston native Eileen Maxson materializes iconic moments from the 1994 cult classic “Reality Bites” in objects, video and installation. For example, for the video “I know it when I see it (Define Irony),” Maxson asked young women in the creative sector she connected with through social media to “define irony,” re-enacting the moment in the film when Winona Ryder’s character, Lelaina, struggles to articulate the definition in a job interview. Here, Maxson talks with Risa Puleo about making work about work; watching the film as a teenager and again twenty years later; emails from Nigerian princes requesting money; Crystal Pepsi, and whale-saving.

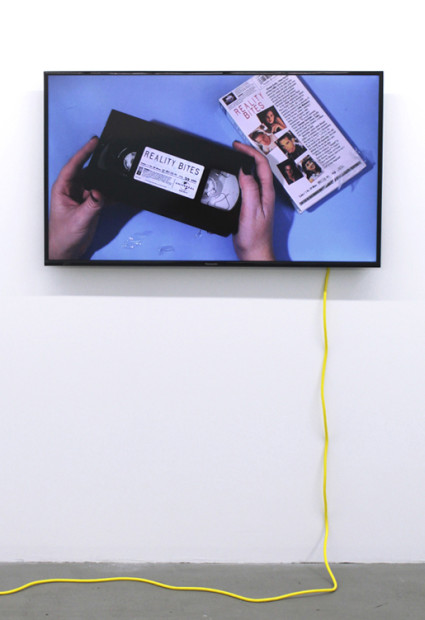

Risa Puleo: Your exhibition includes an installation, “New Releases,” that depicts the ghost of a Blockbuster movie store. In one of your new videos, “Unwrapping Reality Bites on VHS,” you unwrap a sealed VHS copy of Reality Bites while summarizing it: an absurdist way to “show” us the film. On one level, the exhibition seems to be an exploration of the physical spaces and materials of image media: the video store, the movie theatre, the VHS cassette tape, etc.

Eileen Maxson: One thing I’ve thought about is how using the material of tape correlates to the transition of the moving image from film to video to DVD to file, and how that corresponds to the social experience of those images: public movie theatre to home video to personal devices.

The compression of the moving image is a subtext of the work and the film Reality Bites. In “I Know It When I See It (Define Irony),” a VHS copy of women’s responses are framed by a film strip on HD video. This treatment was partially inspired by video store decor, where television monitors played behind film strip cut-outs. The awkward juxtaposition of a video playing behind the image of a film strip, and an HD video of a VHS tape based on a film about someone making a documentary on VHS, functions as my own off-the-mark definition of irony. These types of media “jokes” are important, if undercover, to the work.

RP: You grew up in Houston and Reality Bites, which has become a touchstone of sorts for our generation, is set in Houston. What about the film made you reconsider it twenty years after its making?

EM: Most Gen-Xers and older people that I’ve talked to hate the film. For them it seems like a kind of knee-jerk reaction to seeing themselves and the ‘90s reflected apolitically, which I completely understand. I think this movie found and infected my thirteen-year-old heart just in time. A couple of years later I was listening to Bikini Kill, and, at minimum, felt a more direct connection to a counterculture and politics not yet digested by a Hollywood film.

At the time, I also thought this was a glimpse of my future, artist life. “Cool! I’ll see the Houston skyline when I walk out of my house!” and when things get inevitably unstable, the baby boomer’s good fortune will carry you through. The message was “This is America: you can fret, but you can’t fail.” Nevermind that if a sequel were to be made, Lelaina’s dad’s plant would probably be bankrupt by now.

I also think about this work through my family history and connection to manufacturing, labor and advertising. My great-grandfather was a union organizer, and for all of his working life, my grandfather worked at a Canada Dry factory. At 97, he still loyally drinks the ginger ale that nearly took his right arm off. My father worked at the same factory, but went on to college and and then a job at an oil company in marketing and advertising. With complete sincerity, he still “signs off” voicemails to his kids with a marketing slogan from his company: “Remember, YOU make the difference!” It’s a family tradition to sell what you really believe in.

So, here I am, a fourth generation, now hybrid-maker and marketer of an American product. Only instead of an earnest American corporation seeking increased production and accessibility of their product, the art world model is scarcity and exclusivity. In contrast, while the availability of art should be limited, your personality should be free, branded and promoted. “Digest yourself” is, basically, the nugget of professional development for artists.

Of course, I’m all for getting paid to do art, but ideals and doubt complicate matters sometimes. The dilemma that I really attached to in the film is: how can art (and artists) stay true to their ideals once money inevitably enters the equation. For me, the story of Winona Ryder’s character making a choice between Ethan Hawke, the philosopher poet, and Ben Stiller, the faux-MTV exec, is a love triangle between an artist, her ideals, and the market.

More than any answers, this work offers a lot of anxieties.

RP: Let’s talk more about the allegory of the artist represented in the film. The Troy character, played by Ethan Hawke, is a romanticized version of what a poet or artist is, and is also a douche bag. It is Lelaina who is the “true artist” with a particular vision for her films, which get commercialized when she sells them to her other love interest, Michael (Ben Stiller). The love story aspect of the story is also a battle between romanticization and commercialization of one’s work. That Lelaina makes documentary films that speak to her and her friends’ concerns about college debt repayment and getting jobs reinscribes the “reality” in Reality Bites, as an alternative to Troy and Michael’s approaches.

EM: They’re both complete jerks. Michael corrupts Lelaina’s work in order to gain favor higher up the food chain of “In Your Face TV.” Meanwhile, Troy follows up a confession of love to Lelaina with a laugh and “Is that what you want to hear?” How can you choose between two jerks? I read that in Helen Childress’ original screenplay, she opted for no choice.

RP: You’ve taken iconic moments in the film, the clips that would used for the trailer, and turned them into objects. These are all moments that deal with work or money. Let’s talk about work, making work about work, money and how we participate in a labor system that enables capitalism, commercialization and consumerism in a feedback loop that doubles back on itself.

EM: Early on with this work, I fell down the rabbit hole. For instance, the backstory of the “Evian is Naive Spelled Backwards” begins with 419 scams, the emails we all get, from Nigeria mostly, promising to send money with some caveats. As long as there have been people that really fall for these things, there have also been “scambaiters” that respond and engage with scammers. Their mission is in part to occupy the scammers and save would-be victims from harm. As a part of their work, they sometimes ask scammers to prove that they are really real by sending self portraits following peculiar directions. In some cases, I felt like these images became simultaneous self-portraits of both the scammer and the scambaiter. If you remove the context of people being completely manipulative of each other, it becomes some form of proof of actual communication across the web. It’s people saying, “Are you real, I’m real” back and forth across the web.

Meanwhile, “Mechanical Turk” is an above-board, legal labor site (owned by Amazon) that connects requesters, who often pay exploitative wages (one cent, five cents, etc.) to a world-wide pool of anonymous workers. As a requester you’re strictly not allowed to breach the anonymity of the worker’s identity, but there are no rules about their image. So, of course that’s the first thing I wanted to do. I wanted to know who exactly is on the other side of the screen and these transactions.

Like the baiters, to be sure the images were real, I requested an image that couldn’t be Googled. This is where I came to the scene in Reality Bites where Janeane Garofalo’s character realizes that Evian is “naive” spelled backwards. In the end, I asked workers to photograph themselves with both words on a banner. I paid workers $25, which in relation to the site is a lot actually, but of course still an exploitation in relation to the price I’ll in turn sell that work for in a gallery. I did try to be as fair as possible within my own constraints (first-world problems) and production costs.

In response I received a lot of portraits: twenty pairs are in the final work, as well as random pictures of puppies, kittens and Barbara Walters. I think those people were testing the system; maybe they assumed a robot was “checking” their work.

RP: The other half of the exhibition is about how this labor is subverted into paying back into a system that doesn’t support you. These ideas are best exemplified in the work “Buy a Coke, Make a Difference,” a Big Gulp cup cast in rubber with a two-headed, gold-plated JFK half-dollar coin dated 1994. As you mentioned, the hallmark effect of post-Slacker 1994 is the urgency of wanting to make a difference and complete lack of faith in one’s ability to do so, and how being caught between this urgency and doubt, sincerity and irony was then branded and sold back to us as a possibility attainable through expressing our purchasing power. Today, however, if you buy Fiji water, you’re just an asshole.

EM: Should we really feel so good about ourselves for shopping at Whole Foods? A lot of marketing in the ‘90s certainly tried to condition us to think so. I’m thinking of how much the “Right Now” commercial for Crystal Pepsi affected me at the time. It was so emotional! “Right now only wildlife needs preservatives; Right now change is loose on the planet.” I was like: “I know! It’s true! Mom, buy this for me!”

“Make a Difference, Buy a Coke” has a golden, two-faced Kennedy half-dollar, one emblem of America, encased in a jiggly, clear rubber Big Gulp, which is the container of another American ideal: Coca-Cola. The title is from one of the first scenes in the film. Lelaina says about their future contributions to the world: “I would like to make a difference in people’s lives,” and Troy retorts, “And I would like to buy them all a coke.” In the sculpture both sentiments are inextricably linked, but I also think about it as a “sword in the stone.” Technically, the Big Gulp can be destroyed at some point without harming the coin. I like the idea that the coin, and the optimism of always coming up heads, is still accessible. It’s choice that binds them together.

RP: Your sculpture pulls back the curtain to reveal the mechanisms by which the Pepsi commercial works: a sincere appeal that speaks to all the pressing issues of the day… to sell soda, but Crystal Pepsi isn’t going to preserve wildlife. I’m very interested in how the shift in language from our childhood to now, from “Save the Whales” to “sustainability,” succinctly wraps up how the hope of saving anything has passed and now our focus is not on making things better, but on not making things worse. Hope is just too disappointing; it’s better to manage expectations.

EM: Right, my optimism is definitely tempered, but I also don’t necessarily trust the source. Maybe this is just a part of getting older and jaded? Maybe it was 9/11? Or the wars? Or we’re just repeating ourselves anyways. If the next election is Bush verses Clinton I’ll be so depressed. I have the feeling of standing still, which ties in with the palindrome Evian/naive. That scene is unresolvable to me. Vicky manages to name the duplicity of the products surrounding her, but then buys the water anyway, on a free gas card. It’s an endless, inescapable loop, which I’m also caught in.

But that’s also what I connect with in the film. In some ways it’s more honest; it’s this obvious commercialization of a woman’s life—the writer Helen Childress—and the story about her story being commercialized that ends in a further meta-narrative about her story in the film being commercialized. So, the movie ends with this fake, and it’s just an inescapable movie within a movie within a movie that mirrors the world today. How do you package yourself? How do you package the package?

Eileen Maxson: ‘I was really gonna be something by the age of twenty-three’

at Microscope Gallery, Brooklyn, through August 16. Images courtesy Microscope Gallery.