At the Holocaust Museum Houston, there’s an exhibition called The Art of Gaman: Arts and Crafts from the Japanese American Internment Camps 1942-1946, on view until mid-September. Originating at the Smithsonian and curated by Delphine Hirasuna, the daughter of Japanese American farmers interned at one of the camps, the exhibition contains 120 artifacts made by detainees during the four years of their confinement. It’s fascinating and heartbreaking.

First a bit of background information, as many of us supposedly educated folk know little about or can’t remember the two sentences in our high school history books that referenced the forcible detention of Japanese Americans (as well as Italian and German immigrants) in American-based concentration, P.O.W., and work camps during World War II. On February 19, 1942, two months after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, and under pressure from the military, the public, and the federal government, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which ordered that every Japanese immigrant and Japanese American living in the Western United States report immediately to assembly centers established and governed by the military in California, Oregon, Washington, and Arizona. (In Texas, Japanese Americans were detained with people of German and Italian descent, at the Crystal City Internment Camp.) This affected 120,000 people, who were given one week to sell their homes, close their businesses, and do whatever else it is you do when you are suddenly forced to move.

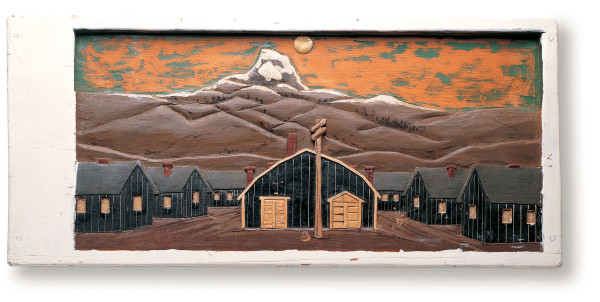

From the assembly centers, which were located at racetracks and fairgrounds, people were sent to one of ten detention centers, with some community leaders hauled off to P.O.W. or work camps. Eight of these centers were in the desert, and two located in swamps. The “concentration camps” as Roosevelt himself called them, were surrounded with barbed wire, where above in guard houses, sentries with guns watched the detainees’ every move.

From the assembly centers, which were located at racetracks and fairgrounds, people were sent to one of ten detention centers, with some community leaders hauled off to P.O.W. or work camps. Eight of these centers were in the desert, and two located in swamps. The “concentration camps” as Roosevelt himself called them, were surrounded with barbed wire, where above in guard houses, sentries with guns watched the detainees’ every move.

Those detainees arriving at the centers found construction of the barracks incomplete, with holes in the floors and walls. Rather than glass, paper covered the windows. An ink drawing on brown paper by Chiuri Obata, a University of California professor who put together art classes for the internees at the Tanforan Assembly Center in Topaz, Utah where he was confined, shows a woman struggling to seal back down the paper covering her windows, as the outside wind pushes sand into her room through the cracks. Another woman makes a futile attempt at protecting the bed with a layer of newspapers that you know will blow off as soon as she lays them down. It was said of these tiny 10-foot square areas, which served as living quarters for entire families, that the only place that stayed clean of dust was the spot on the pillows where people laid their sweaty heads at night.

When they arrived, they also found no furniture: nowhere to sit, nowhere to lay their head or hang their clothes. They had to build everything from scratch, and in most instances had to cobble together the tools to do so before making anything else. In the exhibition, there’s a humble chair made of scraps of 2 x 4s, a chest of drawers veneered in cut-up manzanita branches, a table constructed out packing crates. Because detainees were only allowed to bring what they could carry, if they didn’t bring eating utensils or needed scissors or a knife, they had to make their own, and if they just wanted to feel like a civilized person again, they had to construct their own wallet or cigarette case. Examples of these are on view as well.

Although I initially dismissed it, possibly one of the most potent pieces in the show is a Butsudan created from wood and metal scraps with a bit of paint, by Kichitaro Kawase, an intern at Amache, Colorado. A Butsudan is a Japanese Buddhist shrine meant to hold the Buddha or a religious icon, and was and is an essential part of many people’s homes. It’s symmetrically constructed, and standing in the front of the open Butsudan are two birds, possibly herons or cranes. Above them hang two baskets, filled with carved and painted little white flowers. In the place of honor there’s no Buddha; perhaps there never was. Instead, in the center is a gold scroll with writings on it, perched atop a stand. Making this Butsudan was an act of defiance on Kawase’s part, as it was forbidden to practice Buddhism (as well as Shintoism) in the camps. Even the writing he painted on the scroll was forbidden, as people weren’t allowed to speak or write Japanese. This was particularly hard on the elderly and the Issei (first-generation immigrants) who in many cases knew little or no English. The rebel Kawase, a former poultry farmer and the crafter of the Butsudan, never made it out of Amache and died of a heart attack three weeks before he was released.

Another essential part of the Japanese home was the tea set. A resourceful man who wanted to attend art school when he immigrated to the United States, Homei Iseyama, gathered pieces of slate he found around the grounds of the Topaz War Relocation Center in Utah, and turned it into teapots, cups, bowls, inkwells—you name it—by chipping, carving, sanding and polishing the rocks into rough but beautiful utilitarian works of art. On one teapot, a rose and its stem and leaves curl around the side; a rose hip sits atop the lid, and a gnarly branch acts as the handle. Another teapot, this one more square, has an oak tree motif, with two hearty acorns planted on its top.

For the children arriving at the centers, there was no playground or anything to play with. Nearly half the people in the camps were children, with many of these orphans or children previously living with foster families. The youngest child was three months old, an infant saboteur. Their parents—for those lucky enough to have them—made toys out of whatever they could get their hands on: geisha dolls for the girls made out of wood and crepe paper, and dressed in scraps of kimonos; samurai swords for the boys made from scraps of wood.

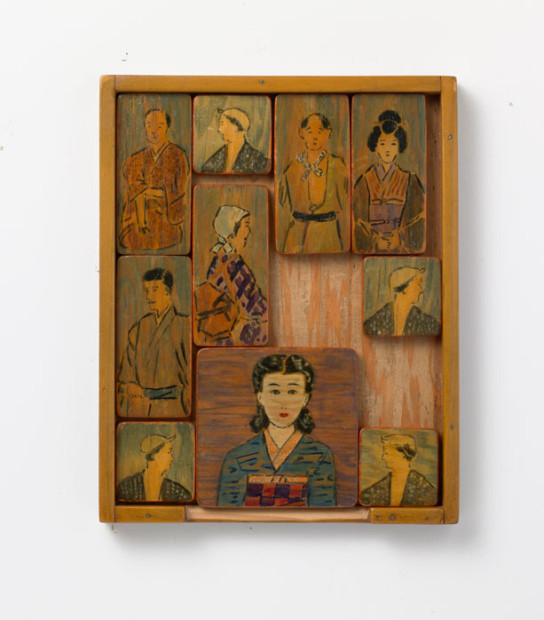

Among the toys, and almost as subversive as Kawase’s Butsudan (at least to me), is a little carved and painted game. Made for his children by Kametaro Matsumoto, a detainee at the camp in Minidoka, Idaho, you played it by sliding little panels of wood around a large Maiden, who you attempt to free from the custody of her parents and servants, a.k.a. the U.S. Government and Camp Administrators. The maiden is ultimately released from her bondage when she is surrounded by four tiny, yet eager suitors (or as I like to think of them: four tiny, yet eager attorneys).

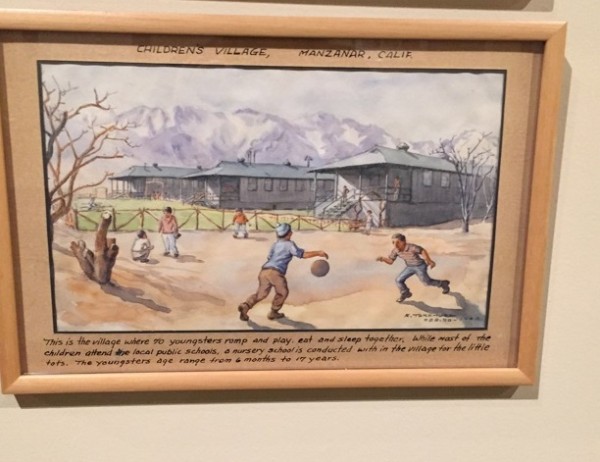

A group of foster children and orphans were sent to live in Manzanar, California, where they were held, within the camp, inside a separate barbed-wire enclosure known as “The Children’s Village.” The majority of these kids were under seven years old. Included in the show is a painting of the Village by a former RKO studio photo retoucher by the name of Kango Takamura. In Takamura’s painting, the mountains and three barracks are in the background, while in the foreground, kids play as kids do, seemingly unaffected by the circumstances they live in. Even the caption seems innocuous, relating that the older kids go to the public school in town, while the little ones stay on site to attend nursery school. If you can call anyone in the internment centers lucky or fortunate, this was in some ways the case of those little ones living at the Village, who perhaps for the first time in their lives were able to experience an uninterrupted period of continuity and a sense of family during their four years there. Most were not so lucky. Sometimes family members were separated. Men who had previously been leaders in their community were relegated to manual labor, and women who had once made all their family’s meals now waited in line to eat someone else’s food in the mess hall. The term “gaman” is a Japanese concept relating to enduring, with patience and dignity, the seemingly unbearable. Nearly every person interviewed who had been interned said that the only way they could bear their time of detention was by being creative. Art and craft classes, such as the one Chiuri Obata established at Topaz, helped in some ways to fill the endless days, and served as a distraction from the despair.

Most were not so lucky. Sometimes family members were separated. Men who had previously been leaders in their community were relegated to manual labor, and women who had once made all their family’s meals now waited in line to eat someone else’s food in the mess hall. The term “gaman” is a Japanese concept relating to enduring, with patience and dignity, the seemingly unbearable. Nearly every person interviewed who had been interned said that the only way they could bear their time of detention was by being creative. Art and craft classes, such as the one Chiuri Obata established at Topaz, helped in some ways to fill the endless days, and served as a distraction from the despair.

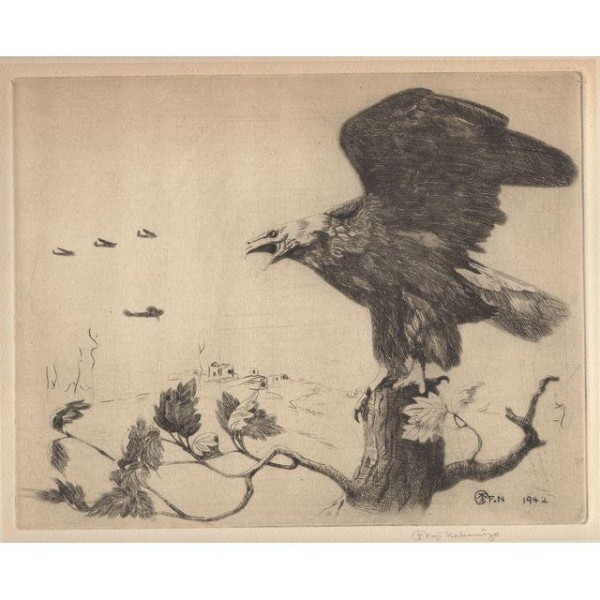

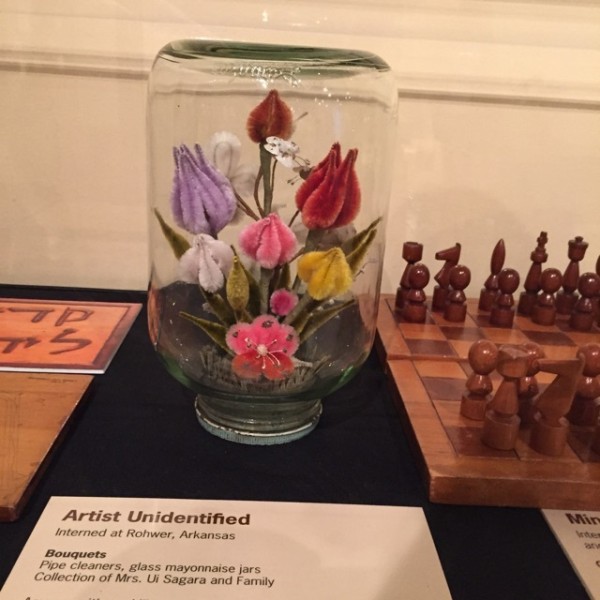

Unlike those enslaved in German concentration camps, the Japanese American detainees at least had the freedom to openly make art, as long as it stayed within its constricted parameters. True, there were some art supplies, though limited, and any other materials you needed you’d have to scavenge on the grounds. Detainees were very clever in using what under ordinary circumstances would have been thrown out or burned on the rubbish heap. In the exhibit, there are perfectly woven baskets made of wire, crepe paper and shellac; a model barracks made of wood scraps and toothpicks; a miniature samurai made of shells; a ring carved from a peach pit; a branch rescued from a fire and carved into a lion, a snake, and a bird of prey. (There are even a couple of proto-Dario Robletos: flowers made from pipe cleaners encased in giant mayonnaise jars.)

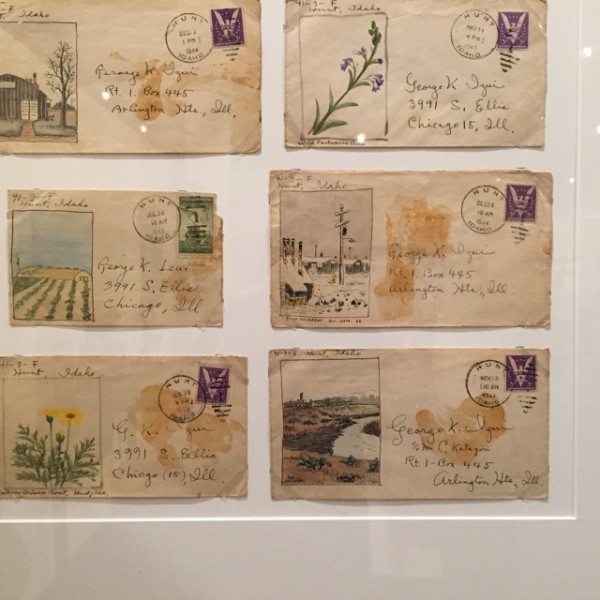

Of those detained in the camps, 3600 enrolled in the armed forces to prove their loyalty to the United States. Victor Izui joined the 442 Regimental Combat Team, which consisted almost entirely of Nisei, second-generation Japanese Americans, who enlisted despite the indignities their families faced. Izui’s father, Mikisaburo Izui, spent time in a P.O.W. camp in the swamps of Louisiana, while the rest of the family was sent to Minidoka, Idaho. His crime? He was a pharmacist, which was considered a leadership role. (Eventually the elder Izui was given permission to move back to Minidoka to join his family.) His contribution to the exhibit are on envelopes addressed to his other son, George, who was given leave to attend college in another state. Regardless of what he endured, Mikisaburo Izui had the grace, like many of the other detainees, to still see the imperfect beauty—the wabi-sabi—of his circumstances, as each envelope is painted, on its front left side, with an exquisite little scene from the camp and its surroundings.

I read an interview by the curator of The Art of Gaman, where she spoke about the purpose of the exhibit:

Raising consciousness of the internment camps of World War II in a non-accusatory manner is a way to bring this sad episode in American history out into the open and to understand how it happened. As well, it helps insure that it never happens again.

Oh, if only that were true.

The Art of Gaman: Arts and Crafts from the Japanese American Internment Camps 1942-1946, on view at the Holocaust Museum Houston through Sept. 20.

3 comments

Beautiful article and art. Thanks Beth.

Insightful piece and the background information on Executive Order 9066 sounds like a Twilight Zone episode. I saw this exhibit in June and was moved by the beauty, resourcefulness and utility of the objects. 21st century Americans need to know that we imprisoned our own citizens because we demonized everyone of Japanese descent.

The other is feared in society even if the other is just like us with different skin color, religion or beliefs.

Very informative article. Thanks for the real backstory on internment.