As for luck, I don’t consider myself a believer. I have claimed being lucky and I have certainly told others “good luck.” But when it comes down to it, I feel like luck has nothing to do with it. Though, a quick assessment of my behavior forces me to recognize that there are things I do that are on par with a batter’s cleat tapping or a gambler’s slot-machine routine. My keys, phone, wallet, and cigarettes have their respective pockets without fail. I have no idea why, but if I put my phone or wallet in the wrong pocket I can’t even walk right. It seems most of us do something along these lines, and Mark Menjivar, an artist based in San Antonio, wants to know about it.

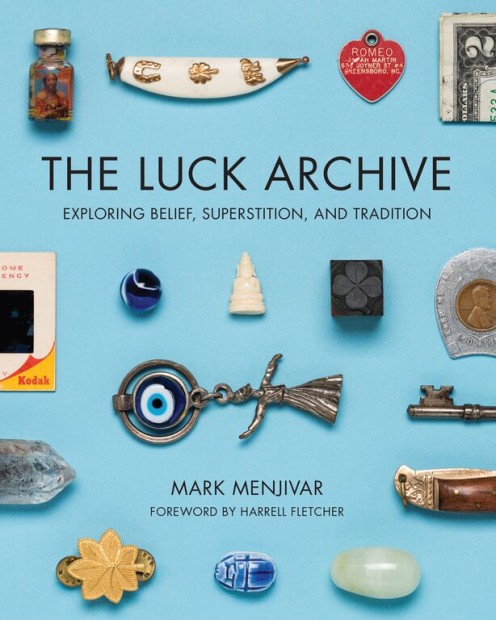

Mark Menjivar’s ongoing project titled The Luck Archive has taken several forms and gone through several iterations since he conceived it a few years ago. The Luck Archive is a collection of photographs, artifacts, and statements about luck, and Menjivar’s idea of luck includes superstitions, traditions, and certain rituals. Selections of the archive have been presented in exhibitions of objects and text (a portion is accessible online) and now more than 100 hundred pieces of the 400-plus item archive have been collected into a book published by Trinity University Press. Here, the collected objects mingle, and the stories behind the objects create patterns, and the collection taken as a whole sends out the impression of luckiness in book form, with the sense that these interpersonal experiences, turned into image and text, are designed as an extension of luck to the reader.

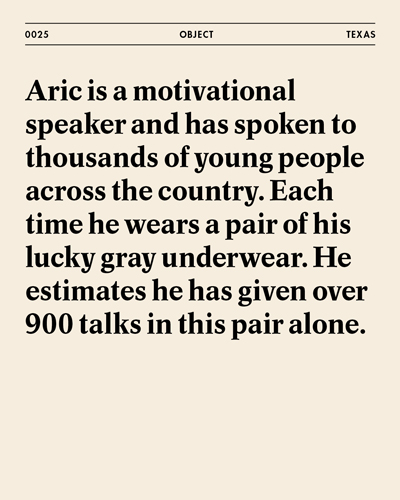

But Menjivar’s printed collection is more than documentary photography of other people’s lucky trinkets. Most of the book’s entries take the form of a crisp photograph of an item accompanied by a short text from its contributor explaining the significance of that object’s luckiness, or their personal experience with the concept of luck. The contributors’ stories are essential to the connections formed among the disparate items; the text and images are co-dependant. The images stripped of the text are striking, but also ordinary; the text is kept to a minimum, often quoted, and without the visual would not be enough to emphasize personal significance. In an especially succinct example, a quality photograph of a pack of Camel cigarettes with the lid partially open reveals two cigarettes flipped upside down in the pack, and is complimented by the text:“Alysha turns around two cigarettes as her ‘luckies’ whenever she buys a pack.”

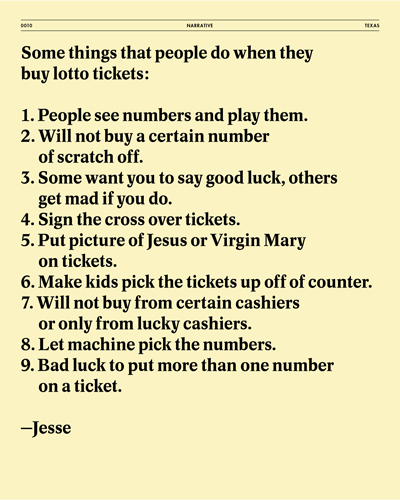

But many more entries are weightier, including statements of belief and luck based on familial religious upbringing, or objects people cherish as having saved them from death. Many border on OCD-like behaviors around lottery tickets and baseball. Luck is present as a commodity, too, via Menjivar’s surveys of specialty stores: think waving cats, votive candles, and sports team fan wear. And luck isn’t harmless; a fair amount of bad luck is included in Menjivar’s archive. Though, interestingly, Menjivar’s luck archiving began when he found four four-leaf clovers pressed inside a book.

Fortunately, Menjivar’s collection is more than the research fodder of an art-ethnographer. Menjivar emphasizes the social aspect of his work regardless of presented medium; he comes from the School of Art and Social Practice as a student of artist and professor Harrel Fletcher. Fletcher’s own work, dealing with the social potential of collaborative work, has spearheaded the Portland State University program dedicated to fostering artists who channel dialogue and collaboration as a medium. As I see it, Menjivar has avoided the art-ethnographic trap of using culture in a didactic way; his approach seems to follow the spirit of Fluxus instructions or Situationists stunts rather than the pronouncements of that charlatan Joseph Beuys.

It’s significant, in an art context, that our sense of luck resides in objects. In art we crave some sort of essence, significance, or cult value in the object, text, or experience. We talk about the magic in art things and seek out other people and their art experiences.

It’s significant, in an art context, that our sense of luck resides in objects. In art we crave some sort of essence, significance, or cult value in the object, text, or experience. We talk about the magic in art things and seek out other people and their art experiences.

But what does a belief in luck say about our structure of beliefs? Superstition lost much of its credibility centuries ago, first through church doctrine and the then by the expansion of scientific understanding. So why do these notions about, say, the foot of a rabbit persist? So many other popular ideas about the mysteries of the universe have fallen out of fashion, like lunacy and fear of tomatoes, so why hasn’t luck?

Maybe because the idea of luck is fun, and communal, and looking at luck as a facet of belief creates an opening into belief and ritual that warrants reconsideration. Menjivar’s project opens up the possibility, if only for a moment, to reflect on our own beliefs and traditions. And more importantly, it opens the potential to connect, through a tangible object, to the ethereal ideas that tie us and these symbols together. “Luck” is probably more-or-less universal; we know beliefs and rituals certainly are. So we see through Menjuvar that these individual events, pointed out and collected by the him, are singularities of universal phenomena. The particular events coalesce in the artist’s archive as a representation of the universal concept of believing.

The Luck Archive by Mark Menjivar is available here.

(All images: Mark Menjivar)

1 comment

Mark enjoyed your article in san Antonio neighborhood

for some reason I acquired a belief that eating birthday cake is good luck and have to have a piece or even a crumb if it is all gone have you heard this one before