I attended a new writers’ conference in Minneapolis over the weekend, hosted by the Walker Art Center. It was called “Superscript: Arts Journalism and Criticism in a Digital Age.”

With that title, you can probably guess the range of speakers: an old-school journalist-critic like Christopher Knight (LA Times) to a radical artist-critic like James Bridle, who gave the keynote after the final session, which was titled “Artists as Cultural First Responders.”

The conference was well-attended, and the organizers, who had never organized a conference before, made some interesting programming choices. (Ryan Schreiber, founder of Pitchfork, was one of the speakers.) The Walker was—no surprise—a great venue for it; very relaxed and accommodating. It’s probably my favorite American museum.

Highlights for me included Carolina Miranda (LA Times, and clearly a crowd favorite) who spoke with such common sense on how (as a writer) to value your work and negotiate with publications on pay, and Claudia La Rocco, whose written speech about her relationship to digital media was gorgeous and visceral while being economical and succinct. I’m a fan.

Here’s a link to the rest of the schedule and speakers and programming (and unedited transcripts) if you’re curious about what went on. Video of all of it should be available through that link by the end of this week, I think. Here are my notable takeaways:

(Note: Some of these things may seem incredibly obvious to some of you, and some of them were obvious to me, too, but still striking in how often they were mentioned in one form or another by more than one speaker or panelist. These impressions are in no particular order.)

1. The golden age of commenting is dead; comments have evaporated into the Twitter ether, migrated to Facebook, or are self-limiting as emoji and GIF reactions. The writers and editors of the publications who once loved and loathed the (often protracted and heated) discussions taking place in the comments section of the online publications they work for agree that commenting peaked around 2010. Now that it’s over they miss the dialogue and feedback, even if they hated the trolling. Even though overall readership has gone up for these publications, the comments section is no longer a reliable marker of a publication’s popularity.

2. Online culture, despite allowing disenfranchised and otherwise isolated voices to speak up and find one another—which is revolutionary in its way—is still mostly just an extension of offline culture in terms of power structures, political points of view, racism, sexism, imperialism, et al. This was stated in one way or another by a number of speakers. Following that thought:

3. The platforms we use to get our words and ideas out there (Tumblr, WordPress, etc) are of course corporate and privately owned. By creating content for them, we’re doing their “labor” for free. These platforms also, in the way they’re structured, have a sort of subterranean influence on how publications are structured, tagged, searched, etc., and this underlying structure is ultimately about the platform’s notion of how things should be and not about any writer’s freedom of expression. We are all being mediated.

I don’t yet know how I feel about this particular point, other than: a) coming up with a whole new and independent platform for writing is way beyond my digital know-how, so I am indeed indentured to what’s already out there, and, b) when Ayesha Siddiqi made the point that when she (presciently) moved the publication she was in charge of (The New Inquiry) off its previous platform just before that platform evaporated (or their arrangement with it did), she helped the magazine narrowly escape being wiped out entirely, including its entire published history.

This just serves as a note: Corporations can manipulate and censor anything on their platforms at any time, so fundamentally, your stuff is never safe from censure or erasure. My extrapolation: Obviously, corporations don’t want to scare away customers by being jumpy or fickle, but they each have their own policies about how they deal with government agencies (or others with power) demanding I.P. addresses and other identifying information, and corporations want to do business with governments (and others with power).

4. Visibility is not power. Visibility can be vulnerability. We know this, but as publications and writers strive for visibility, they should appreciate the dangers that come with it. Flip side: invisibility can be powerful, and the people pulling the most strings in our society tend to be, intentionally, far less visible.

5. The handwringing over ownership, copyright, and piracy is overblown. Text and narrative have always been subject to change, depending on who gets their hands on it and what message they want to manipulate and communicate. Wikipedia (I’m also thinking of the Constitution and all religious texts) is a good example of this, but all text is subject to the same treatment. Attempting to lock down ownership and narrative is, over the long term (decades, centuries), futile.

6.. “Embrace your boredom.” Claudia La Rocco said this, and as a writer it stood out to me. This is, for those of us whose brains never turn off, an especially valuable permission to trust your instincts. I’m so ADD and intensely interested in so many different things that, at my age and experience level, when I encounter something and think: This isn’t interesting to me, I should move on. There’s a whole world out there and not a lot of time.

7. Digital-age publishers are obsessed with the idea of community; of building it and/or finding it and/or representing it. There is no such thing as “community,” at least as far as it relates to how people consistently or predictably respond to the things you put in front of them. Therefore, don’t take any “community” for granted. It doesn’t really exist.

8. My sense if that, for those of us who are addicted to words and reading: We aren’t about to become expert visual storyteller/critics (i.e. using images to respond to images). We’ll still use words, but we’re not sure where we’re going with it yet. But it needs to be, in a way, as accessible as the imagery it’s about. Ben Davis’ keynote, delivered at the end of the first day, was called “Post-Descriptive Criticism.” The arc of his talk, by my interpretation, was about how the language we’ve used to write about art over the last century has been both highly descriptive and elitist. Up until the digital age, most people simply didn’t have easy access to images of the art being written about, so heavy description was always necessary, and also, the philosophical and intellectual demands of the work inspired a kind of academic elitism to claim it and lock it down as its own. Now that everyone has easy access to all images all the time, highly academic language has to give way to new ways of responding to art; we are all at square one.

9. Can one assert authority if one only writes positive reviews? The general consensus seemed to be “no.” But not all critics agree on only punching up (i.e. only criticizing those with relative power in the art world, be they artists, institutions, collectors…) when writing negative criticism. This issue did not get ironed out. Not surprising in a room full of opinionated people. Plus of course, several people joked: “Have you ever seen a positive review go viral?” The answer of course is no. Knight made it clear that in this digital age, even as an old-school critic, his real job is to attract readers. This is a numbers game.

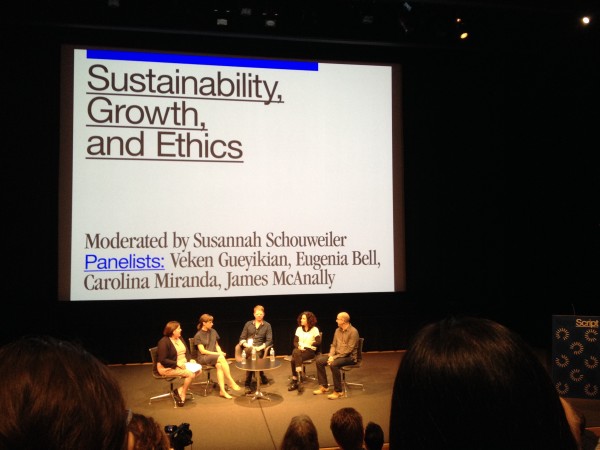

10. It was Carolina Miranda, Susannah Schouweiler (I really like her) and Eugenia Bell who, in a panel, stressed the value of writers turning in clean copy (on time) and how much time it costs editors to have to clean up and rewrite copy, fact check, find images, spell check all names, etc. Miranda says she’ll write for smaller or broke projects but demand just a pinch more in payment than the project would pay a lesser writer (like, $10 more), because she turns in really clean copy and on time. It made incredibly good sense. She was better than most at understanding how abstract and fluid we should be about the value judgements around how much to pay any particular writer.

P.S.: Good news! Art criticism is not dead.

3 comments

Art criticism will never die, but it will always be as fickle/illusive as the art in it’s wake. Adaequatio is required for any true exchange between reader and critic, so build a bridge everyone can cross.

“We think artists are ahead of their time, but actually they express where we are now. We don’t recognize where we are, so their art seems strange.” – Nancy Wilson Ross

“To create is divine, to reproduce is human.” -Man Ray

Art criticism will never die, but it will always be as fickle as the art in its wake. Adaequatio is required for any true exchange between reader and critic, so build a bridge everyone can cross. – Art Shirer on Good news! Art criticism is not dead.

Art in art criticism’s wake?! Only Dallas art trails criticism. The only possible function of art criticism is to document recent history.

Thank you for introducing me to a few new art writers. I’m obsessed,too,and can read this stuff all day (and night) long. The speaker videos are up, too.