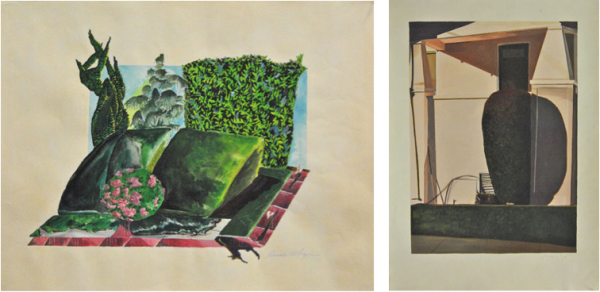

Helen Altman, Cover Your Nut, (detail), 2014

Two exhibitions by established Texas artists that explore the fraught and often funny zone where the natural/unnatural collide closed recently in Houston.

Susan Whyne, Untitled (Entrance #37), 1970-72 and Untitled (Entrance #56), 1974

In 1969, Susan Whyne moved from New York to the San Francisco bay area, and began drawing and painting what felt like a completely different world, which she describes as “singular houses that had yards with ‘nature’ in front to lead you inside.” Whyne’s “lawnscapes” still feel fresh, conjuring David Hockney’s California cool and Edward Hopper’s sense of light and desolation.

Susan Whyne. Untitled (Entrance #56), 1978 and Untitled (Entrance #60), 1975

Her abstracted, sometimes off-kilter perspectives of home façades never include the humans that occupy them. Instead, the focus is on the formal play between architectural and natural flourishes. In Entrance #45, a tiled path winds between totemic hedges; nearby a pile of rocks is stacked like impromptu sculpture. In another, a stone wall becomes an abstract barrier with a green hose coiled in front of it set off by bright red concrete. The paintings range from loose and funky, almost alien-looking collages of lawns and hedges to photorealistic snapshots that capture a particular sunny California day. Installed salon-style in a dense and irregular grid, we can follow Whyne’s roving eye through a visual feast.

§§§§§§§§§§§

Helen Altman, Cover Your Nut at Moody Gallery, installation view

Helen Altman’s Cover Your Nut at Moody Gallery feels like a mini-retrospective. An eclectic mix of recent work ranging from found object sculpture, child-sized lion costumes, and wireframe birds, to incredibly precise paintings of trees, the work feels coded with personal meanings, revolving around how humans use animals to tell our own stories.

Helen Altman, Blackbird2014

A sense of the past and childhood is overwhelmingly present in the work; many sculptures use antique, child-size objects and stuffed animals, perhaps alluding to a moment in life when the human/animal worlds are closer as a child seeks comfort in a stuffed animal. Sleeping Rabbit uses objects worn from age and time: a stuffed rabbit stands in for a child asleep in a small bed. In Hands of God, two plaster hands are mounted on a child’s table, casting the shadow-silhouette of a rabbit on the gallery wall. Does this god-creator-of-animals sense of power exist in even such a banal, playful gesture?

Helen Altman, Sleeping Rabbit, 2015

The exhibition is full of these kinds of questions. The natural world is respected for its complexity and power without being worshipped with clichés. Altman’s laborious paintings of trees show every leaf; each tree’s common name, Latin, scientific name is inscribed underneath, as if torn from an encyclopedia page. Altman casts organic materials like dried hops, dried artichoke, and black sesame, in the shape of human skulls as odes to mortality. The commonplace raw ingredients of our world are reshaped into ephemeral artifacts that playfully allude to our own demise. Altman’s objects are meticulously made and direct, yet conceptually rich and often humorous without easy answers or messages.

Susan Whyne’s Entrances 1969-1977 exhibition of paintings on paper at Art Palace closed March 28, and Helen Altman’s recent work on view at Moody Gallery closed on March 21.