There’s a long tradition of artists’ correspondence. Two minds of great intensity come together to reveal thoughts about work, life, and friendship; think about the famed letters between Sol Lewitt and Eva Hesse, where the fodder of creative endurance has inspired countless other artists. The exhibition currently on view at Pump Project is a product of slightly different kind of correspondence between artists Jessica Mathews and Kyle Evans.

Kyle Evans and Jessica Mathews’ friendship and collaboration was manufactured by a third party, curator Rebecca Marino. Marino introduced the two with a two-person exhibition in mind; the result however was a dynamic collaboration that produced the works in 000000. Mathews was on residency in Iceland and Evans remained in Austin for the duration of the exhibition’s development. The back-and-forth emails and exchange of files of information over 4,000 miles of separation forced a creative constraint that was serendipitous for both artists. Mathews’ work is based in her exploration of digital representations and the marriage of color and light in relation to computer code. Painted pixels and text pieces of hand-written hexcode make up her most well-known projects. Evans, a sound designer and electronic instrument maker, creates work that investigates the relationship between the analog and digital world; he makes installations of circuit boards, old TV monitors, and wiring, which results in a poetic mess of electric discard.

The exhibition is their productive interaction. Hexadecimal black (000000) was the starting point for both artists—it’s black the color and the computer-code language of black. Evans first created a video loop of the blackness on two monitors, filmed them and then spliced that together onto another older television screen; it’s called The Voltage Potential of Nothing. He sent the footage to Mathews, who extracted one pixel from each of the 500 frames and painted each one onto a grid, #000000: 1 Pixel: 500 Frames 1-8. Most of the pixels are black, but some are surprisingly colored, and the beauty of these digital extractions is re-interpreted with a painterly hand of thick impasto. She then took her painted pixels and shot them all for a looping video in #000000: 1 Pixel: 500 Frames 1-8: 00:01:23. It results in a strange black background with the center-oriented pixels flashing quickly on an ancient TV screen.

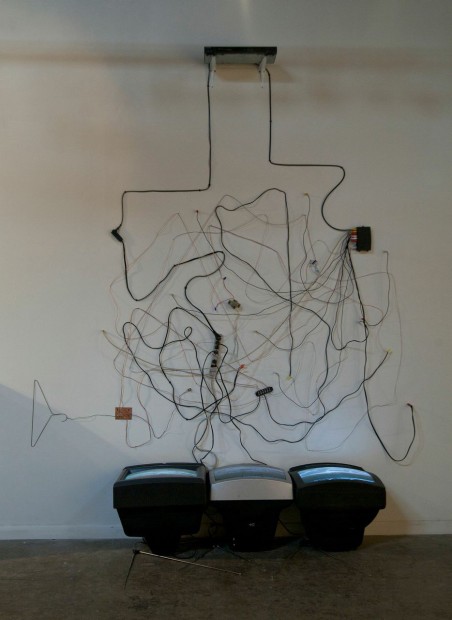

The exchange continues from here. The humanization of that digital scribble by Mathews, via her painted application of blackness pulsing through tangled technology, is pushed back into the digital interpretation by Evans in Digital to Analog Conversion. It’s an imposing installation of wires and screens and a wire clothes hangers, along with a transistor that serves to wind the painted pixels around a spaghetti-bowl of dusty junk technology. It spits out a hypnotic video of choreographed feedback that changes its dance with every twitch of the antennae or detected presence of a body.

Mathews’ response is two of her dense and exhaustive hand-written hexcode sequences, Hexadecimal Sequence (I) and Hexadecimal Sequence (II). She writes out the coding for one frame from Evans’ digital jumble, and these works speak to the correspondence aspect most poignantly: two humans communicating via computers, dependent on the massively complex internal systems of coding. It’s the way in which their human language, the symbology of sounds and characters, is reinterpreted by artificial intelligence and put into a far more precise language for a vast network of computers, which speak to each other as translators for humans. Mathews’ process creates a simulacrum of the glimmer of humanity within the machines we created. Her ritualistic practice of transcribing the hexcode, the computer language of color in JPEG format, is a performative and tributary action of deep reverence for her language and a shared language, and its place within the universal language of computer systems.

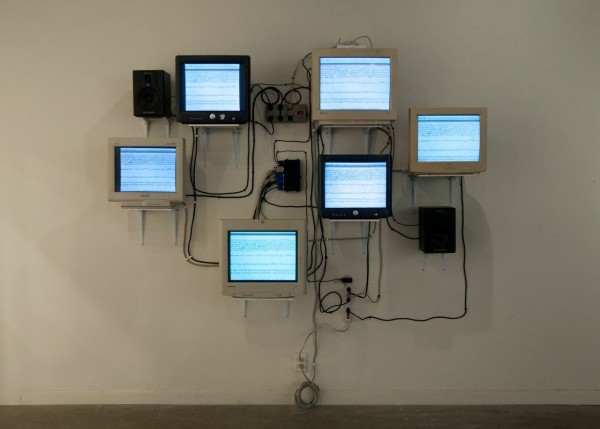

Evans’s follow-up, Hexidecimal Distortions, is an eerie installation. He put code through a program that forced the computer the take the JPEG compression and spit out interpretive sound (I don’t fully understand the process). Six 30-year-old computer monitors play videos of the written hexcode sequences, and wonderfully strange sounds slither out like vapors from two speakers. The show’s curator, Marino, told me that the raw sound that comes from the interpretation is unlistenable noise, but that Evans trained the beast not to scream but rather to sing by tweaking his program, thus transforming the cry into a meditative background song that swirls around the entire exhibition.

Lastly is an entirely collaborative video work, L#000000p. This quiet piece shows a strip of video in the middle of flat black screen; the stripe of little rectangles of colored light seem stagnant at first but on closer inspection are slowly morphing and individually fading into blackness. So black is an opener to this exhibition, which culminates as a slow fade back into the blackness.

The success of the show is that its cold technological matter renders the intimate quality of playful conversation. Mathews and Evans’ individual visions are not compromised by the collaboration but instead enhanced by this artistic symbiosis. This show is sharply curated by Marino and richly composed by the artists; it’s a playground by two individuals grasping for meaning as they wander the maze of their own relationships to technology and meet up in the middle of it.

Jessica Mathews and Kyle Evans: 000000 at Pump Project, Austin, through April 4.