I’m fine with being late to a party if I need to get a fix on the full range of my feelings about it, and in the case of a clever marketing stunt pulled by Helly Nahmad Gallery last fall in London, I’ve run through every one of Kübler-Ross’ stages of grief and beyond to land here at mild disgust.

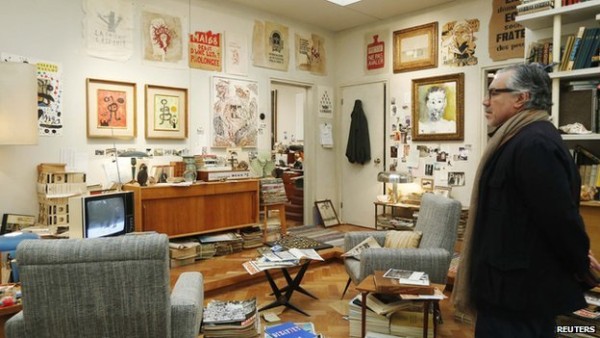

At Frieze Masters (sister of the original Frieze Art Fair), which specializes in works made before 2000, Helly Nahmad Gallery presented, instead of the standard white-cube booth, a fully realized bohemian “apartment” belonging to a fictional character referred to as “The Collector.” Designed to look like a Parisian flat in 1968, the time-capsule interior was a Wes-Anderson worthy imagining of the digs of a veteran writer-philosopher who fully inhabited his era. The set was a shabby-louche paradise of back-issue periodicals, early and mid-century furniture, first editions, new-wave cinema memorabilia, overflowing ashtrays, piped-in Miles Davis, dirty dishes in the kitchen sink, and a salon-style hang of actual artworks (for sale of course) by such luminaries as Picasso, Miró, Fontana, and Magritte.

I didn’t see it, but it was well documented, and an artist-writer friend of mine did see it and bring it up on social media as a discussion topic. The gallery of course hired a set designer to pull off “The Collector” and according to gallery representatives and reports at the time, it was a major attraction at the fair, to the degree that as some people (I assume older viewers) walked through it they wept. I also assume this response was from an overwhelming nostalgia for a lost time and sensibility—for a time in their lives when they were entirely engaged with the culture around them, and able to invest sincere energy on it. Younger viewers oohed and aahed at it, though I imagine that was more of a Selby-esque appreciation, and they could pick up some tips to take back to their own Apartment Therapy-ed, carefully aestheticized lairs.

Looking at photos and video of the booth, I see a place that looks not terribly unlike—at least in part—the houses and apartments of people I know and love, and of my own historically cluttered walls and bookshelves (minus the high-dollar art), but of course the gallery is just trying to bottle and sell the idea of intellectual curiosity to the new collectors who come through, and to push a heightened sense of context for the work itself. As a tactic and a fair experience, it is indeed a very nifty idea. It is cynical. Patronizing, insulting. It is effectively rendered nostalgia as a trojan horse for art sales. I might have wept, too, though at that moment I might not have understood why.

Western pop culture’s nostalgia obsession has reached an absurd level, and every decade since the beginning of the last century is getting the romance treatment to a startling degree. What this means for the art world in the long run, I’m not sure, though it’s caught up in it too, and I believe the market will use nostalgia more and more to (re)contextualize and sell work. And why not, since every other industry is using it as a marketing tool.

So, advertising, yes, but nostalgia has increasingly infiltrated narrative television and movies, magazines and newspaper trend pieces, music, design, fashion (of course). This is our world’s desperate grasp for a pre-digital existence, when everything (we believe) was slower, deeper, calmer, more thoughtful—more substantive and worthy. In 2011, the writer Simon Reynolds in his book Retromania proposed that the cycles of nostalgia have been accelerating since 1964, but as the internet’s bottomless universe of information expands exponentially by the day, I wonder if even he could have fully predicted just how addicted we would be to nostalgia only four years later. It’s all just so available to us now.

I’m not immune to it, and I think references are fine; we all need them to understand where things come from and to get a sense of where we might be heading. Context context context. Working artists and anyone in creative fields have long understood this. But if the art world starts to depend too heavily on making new art stars out of dead or nearly dead artists and scrambling to revise and revere art history at the expense of mid-career and younger artists making work now, I fear our understanding of the whole reason art gets made at all is completely undermined. There is an endless of supply of forgotten artists from recent previous decades. This trend could go on indefinitely. If today’s best 45-year-old artists watch this pattern expand, they can perhaps assume some level of appreciation about 20 years after their deaths, once the culture-mongers of 2074 decide that 2015 was really pretty fascinating. Though maybe the superficiality of our current digital era will never seem as nostalgia-worthy as, say, 1968.

I understand there’s too much new art out there and not enough of it stands out (perhaps because so much of it is either a pastiche or mashup of earlier art), and I understand our attention spans are the shortest they can be without shorting out entirely. But this reliance on the (long) test of time to reassure us of something’s value—and in the art world collectors and curators seem especially guilty of this right now—runs opposite to simply being alive and present in the world that exists and is revolving right now. And living artists have mostly, since the middle of the 1800s, been concerned with responding to their current world and making new things in new ways. The digital industry and its innovators have taken up that baton, while the rest of our culture seems obsessed with mining the past, and it’s getting worse by the day.

9 comments

1) Often artists in the recent past didn’t get their due as young artists for dumb reasons (for example, because they lived in the wrong city, they lived in the wrong country, they were women, they were black, they died too young, they had bad luck, etc.). I think the rediscovery of these artists isn’t about nostalgia but about finding and revealing good art regardless of vintage.

2) When I looked at the photos of the Helly Nahmad Gallery’s life-size art diorama, I wasn’t filled with nostalgia but recognition. That’s what my apartment looks like–crammed with art and books, messy, and yes, dishes in the sink. The only real difference is the technology on display–no typewriters or tube TVs in my apartment. It’s something I’ve recently become interested in–the difference between people’s cluttered personal art environments (John Berger wrote about this) and the “white cubes” of galleries and museums. I’m not saying one is better or worse, just that art lives very differently in each place. Helly Nahmad Gallery created this environment to sell some art art an art fair–so what? In a way it feels like truth in advertising–if you buy art, it’s probably going to look like this. Not like a gleaming white cube and not like a photo spread in Architectural Digest.

I agree- if the Internet had existed at midcentury, a lot more artists would be in the canon now. We’re just repairing our cultural oversights, and the process will be mostly over in 10-15 years, and the artist-rehabilitation craze will slow down.

There are two things that make “undiscovered” or “rediscovered” older art so appealing to the establishment/collectors these days, and keeps them at the task of unearthing more of it all the time: 1) the age of it gives it that psychological patina of gravitas (the nostalgia factor) with which it’s easy to dupe the public opinion into believing it’s great, and 2) (and much more importantly) it is waaaay cheaper to buy the overlooked old stuff than work by the major art stars of ours or any era, and collectors can therefore create and control the market for it. Creating context = money magic!

I don’t know how soon that will end. 10-15 years seems optimistic to me, but perhaps.

I just read this in my studio – and although my wife and I are, unsurprisingly, married and we therefore talk about art a lot, we’d never discussed this particular subject. However, I well remember Helly Nahmad opening in Cork St in the late 1990s, and the peculiar stir it caused at the time. C’s article reminded me again of that moment.

When Helly Nemad Gallery opened in London – it moved in next door to Leslie Waddington in 1998 and apparently came out of nowhere. They were fantastically monied, and so arrived on day one with an inventory of serious Picasso, Magritte and so on. They were one of the first galleries in London to mount shows that looked like they’d boxed up a job lot from a museum. It was bizarre at the time, if you knew how the rest of the commercial art world worked – it was overnight super-blue-chip secondary dealing, and all done in very much the white cube.

Later, to gain kudos as I remember, Matt Collings and Emma Biggs were asked to do a catalogue and/or come in and lecture(?) on what can only be said to be a spectacular show of small late Picasso paintings and drawings. And then Adrian Searle was asked to give a talk (this is all from memory and about ten years ago).

The quality of the work or the speakers wasn’t in doubt, but the manner in which a superwealthy new gallery could muscle their way so quickly into the market place left a strange taste to some.

No surprise then, that years later, the gallery devise an “ideal” viewing space for these virtually unobtainable art works which seems to imply that the true meaning and provenance of the work is actually free from the immense multi-million wranglings of those that have and will put them on the wall. These works will of course end up in some white cube/bank vault or whatever, and will unlikely ever see such “fantasy apartments” where art can pretend to be only art and not investment.

Which collector out there is so stupid as to be convinced by such a comedy “authenticity” gambit. The idea of course, is that this grimy ‘real’ faux context is meant to restore to the work its original cultural intent and therefore meaning – spiked with a dose of 1968-ish edgy politics – that has since been essentially steam-cleaned from the work through decades of speculation and investment. It’s like an optional extra on a car – Performance Pack, Vision Pack, Extra Meaning Pack, etc, etc.

Picasso’s own house would have looked far grander, by the way.

It’s the art world uber-dealer/collector equivalent of “Derelicte” in the seminal Zoolander. What next, Larry Gagosian on his own stand sitting in a Citroen 2CV – and if so, an original patina first production version with a roll-back canvas roof?

And to Robert Boyd above – no, if you buy the art in that booth, I very much doubt it will end up in an apartment like that; it will very much be in a gleaming apartment and in a photo spread of Architectural Digest – supposing that is, the lawyers and insurance company of the owners allow it – and/or there’s time to get it out of the vault in Zurich and have it shipped temporarily to an unused apartment for the duration of the photo shoot.

It’s a question of taste, and lack of truth, not truth in advertising. Gagosian’s booth in Frieze NY when I was last there was truer, using about 2000sq ft of floor space then hanging a dozen Ed Ruscha’s in a line on one wall, and not using the rest of the walls at all. It was a statement about art fair real estate as much as anything. At the edge of the booth were a pair of Pierre Jeanerette 1955 armchairs – the ultra expensive ones that you rarely see on the market, and a Charlotte Perriande coffee table. If you know your stuff, you’d know these actual chairs would have recently re-sold at Sotheby’s for six figure sums. Chances are, they were also for sale at the booth – which is why they were there. As Mr. Gagosian likes to say, “everything is always for sale”. Even the notional semblance of fake authenticity.

The applique grime around the door handles in the Helly Nahmad stage set is like ‘the gazillion dollar club’ playing at being Joe Orton or John Osbourne. And now what – the new collector gets the work home, and hires a designer to make a fake 1968 ‘Prick Up Your Ears’ collector room at the Aspen mega house? And a Francis Bacon studio for the London School stuff, and then start brushing their teeth with Ajax, rubbing theatrical rouge on their cheeks… and all that other Bacon-y stuff….

Ne travaillez jamais! Sous le pavés, la plage! http://41.media.tumblr.com/tumblr_lsnf9upvCz1qced37o1_1280.jpg

Or some damned thing like that from 1968 (MLK & RFK assassinations, Andy Warhol’s shooting, Tet offensive in Vietnam, Chicago police riot at the Democratic convention, etc.)

In this world today while we’re living some folks say the worst of us they can

But when we are dead and in our caskets they always slip some lilies in your hand

Won’t you give me my flowers while I’m living and let me enjoy them while I can

Please don’t wait till I’m ready to be buried and then slip some lilies in my hand

Foggy Mountain Boys

I liked it! In pictures, at least, the booth suggests that in the good old days great art was not inconsistent with a middle class lifestyle. It still isn’t, just not with that particular art, which has been boosted (stolen!) out of that context into the blue-chip stratosphere.

You said what I was trying to say much better than I did.

I’d stick and stay with “denial”!