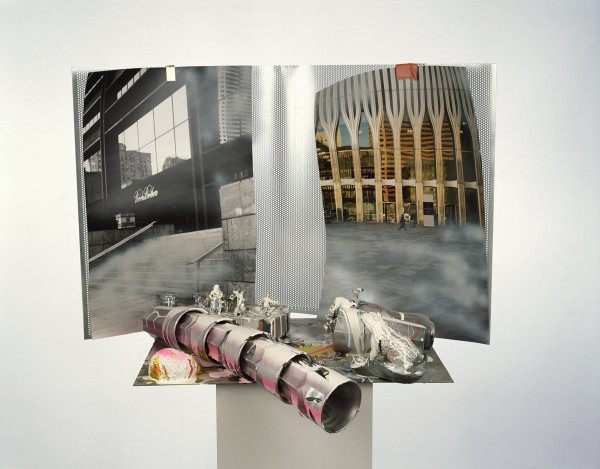

When I edited this week’s Glasstire Top Five video I was happy to hear Rainey Knudson exclaim loudly about Isa Genzken’s big retrospective at the DMA: “What is it that makes some artists be able to make trash art so well, and some artists so badly?” Knudson calls it trash art; I call it abject. Tomayto, tomahto; povera; assemblage, piles of sleazy junk. When it works it’s utterly surprising and Genzken is very good at putting cheap and weird stuff together in the most unlikely combos that somehow allude to historical moments or her personal obsessions with politics and eras, including 9/11, children videotaping a beating of another kid, and an underground gay disco scene in Berlin. We also get to know her fixation on skyscrapers and clothes, drinking and windows.

And in her hands, due to her very special brain wiring, her version of piles of sleazy junk is utterly evocative of the mood she’s going for. Sadness and loss are recurrent themes, as is affection for close friends (fellow German artist Kai Althoff figures heavily in the show), and anger about a vulgar and exploitative political world. Her wit is here, too, slicing through it much of it. Looking at her work of the last fifteen years is like hearing a new, made-up language spoken for the first time and yet understanding every word of it.

And in her hands, due to her very special brain wiring, her version of piles of sleazy junk is utterly evocative of the mood she’s going for. Sadness and loss are recurrent themes, as is affection for close friends (fellow German artist Kai Althoff figures heavily in the show), and anger about a vulgar and exploitative political world. Her wit is here, too, slicing through it much of it. Looking at her work of the last fifteen years is like hearing a new, made-up language spoken for the first time and yet understanding every word of it.

Given her fixation on stereo equipment (and forgive me), Genzken’s antenna is picking up on a fuller spectrum of emotion and her transmitter is putting out a more nuanced range of reaction than most artists are capable of. Ninety-nine percent of newly minted MFAs attempting this type of thing—they often do, and nowadays we’re seeing bad trash art everywhere—will merely mimic its features, focus too politely on composition and making it all look artfully random, and fall far short of it hitting any communicative bullseye. But Genzken isn’t pretending, and she is fearless. She’s driven to locate her own unusual truth and she delivers it with utter conviction; she offers zero apology for how ugly or difficult her constructions are. She knows clearly what she’s communicating here and she’s confident you should and will see it too. And so we do.

Given her fixation on stereo equipment (and forgive me), Genzken’s antenna is picking up on a fuller spectrum of emotion and her transmitter is putting out a more nuanced range of reaction than most artists are capable of. Ninety-nine percent of newly minted MFAs attempting this type of thing—they often do, and nowadays we’re seeing bad trash art everywhere—will merely mimic its features, focus too politely on composition and making it all look artfully random, and fall far short of it hitting any communicative bullseye. But Genzken isn’t pretending, and she is fearless. She’s driven to locate her own unusual truth and she delivers it with utter conviction; she offers zero apology for how ugly or difficult her constructions are. She knows clearly what she’s communicating here and she’s confident you should and will see it too. And so we do.

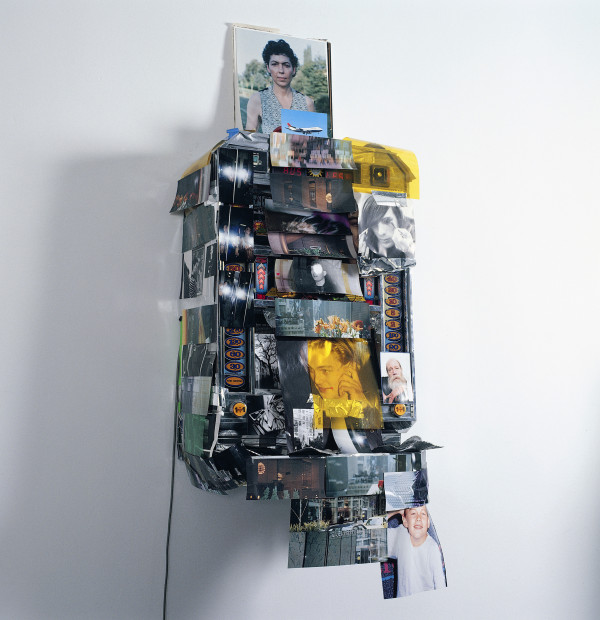

A few miles away off of Lower Greenville is a smart and tiny show (with a closing event tomorrow night) by current CentralTrak resident Jeff Gibbons, a guy raised in Detroit who found his meandering way here and will have a bigger solo show at Conduit in a few months. At Two Bronze Doors, an alternative art-and-music venue set up in the living room of an old house, Gibbons has cleared out all the furniture to show two videos and one photograph, and it’s all very quiet and stripped back. But one of the videos, projected low on a wall near the floor, got to me.

It’s almost a Readymade and the kind of thing most people would happily throw out: an unedited VHS video shot on one Easter Sunday in 1988 by his parents in and around his family’s Detroit house as they documented their stuff (stereo, TV, car) for insurance purposes. But these parents also got drunk and high and had some fun taping the whole family (and some neighbors)—including a six-year-old Gibbons the future artist—hamming it up for the camera. The era and milieu of the scene is so pinpoint specific that it pierces time, expands, and becomes weirdly universal, and the current Gibbons is well aware of this. The family dynamic, particularly between mom and dad, plays out like barely submerged Chekhov to the soundtrack of the Pretenders’ bouncy “Don’t Get Me Wrong.” Dad acts patient but he’s wound tight; mom is laughing but unraveling, determined to blow off steam.

Gibbon’s blue-collar street looks like what Americans have decided mid-America must have always looked like. Aspects of it are as cozy and familiar as “A Christmas Story,” and other undercurrents echo the dark cheapness of Harmony Korine and the mounting dread of John Cassavetes. There is no high drama here, but I became intensely curious about fates of the people on screen. There are shaky passages when the camera tips sideways to show us the brown lawn, jerking shots of the empty street, too-long segments of watching the kids dance around the shaggy living room. We don’t deal in this kind of accidental banality much anymore; iMovie and Vine have seen to that. But we can sense that those boring, unshowy moments are where the truth is, and it’s often unsettling.

Gibbons didn’t even officially transfer the VHS format to digital; he simply filmed the video with a newer camera as it played on a TV screen, and we’re seeing the footage once removed. This gives the whole an even more grainy and distant look and sound. The decisions he made around this piece—how it’s produced and displayed, its intentional lack of editing and how that leaves in all the uncomfortable minutes of randomness and boredom, and the understanding that his family and childhood home come off as happy and sad and unexceptional as everyone else’s—are, I believe (and based on my experience of his other work) the products of Gibbons’ good instincts. And while these same instincts seem to be urging him to move away from Dallas in the next year, we should look forward to what he else he can show us before he leaves.

4 comments

Great pairing of Gibbons with the Genzken retrospect. I also was drawn in by Jeff’s home video. It was so epoch and personal. But in my visit I wasn’t aware of his process. Fantastic showing. Can’t wait for the show at Conduit.

It’s true: in Genzken’s case “trash” is less accurate than “plastic crap from Canal Street.”

” And while these same instincts seem to be urging him to move away from Dallas in the next year, ”

Details ??? 🙁 🙁 🙁

“Ninety-nine percent of newly minted MFAs attempting this type of thing—they often do, and nowadays we’re seeing bad trash art everywhere—will merely mimic its features, focus too politely on composition and making it all look artfully random, and fall far short of it hitting any communicative bullseye.”

so true, so true……