Otis Jones and Bret Slater are no strangers to one other. Theirs is a strong personal relationship with a shared admiration for a particular kind of art making. Their work is related, but different. Both artists approach painting as though they are making models of painting, and their models churn out paintings that are, respectively, anti-illusionistic and personifications of paintings.

Otis Jones, Two Lines One Moved, 2014. Acrylic on canvas 24 x 24 x 3½

This is the first time I’ve seen Jones’ work face-to-face, and it is impressive how he plays with the idea of space. Tactile and inviting, the work is calculated to be a smack in the face of formalist dogma. A pancake stack of glued plywood, gouged furrows, discs of thickly applied color, and lots of distressed surfaces replace the pure opticality of high modernist painting. What you see is what you get, just in case you thought painting should depict a field of illusions. Instead of wanting to virtually inhabit them, we want to use them like furniture. Jones’ “paintings” — they are more like relief constructions that refer to an idea of painting — serve up a buffet of high modernist art theoretical demagoguery turned on its head. They exude resolve in the way Hercules might have expressed it as he approached the task of cleaning the Augean Stables: this is going to be a messy job, and I might be some time.

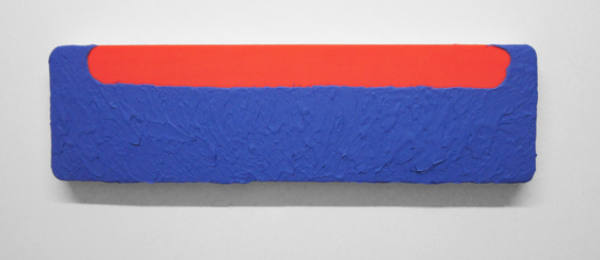

Bret Slater, Driggs, 2014. Acrylic on canvas, 22.8 x 76.8 cm.

Slater’s work is equally removed from being an earnest illustration of anything remotely like high modernist principles of taste and decorum. These small works speak to us, too, but in a different register, a more churlish, impish, and contrary tone. They’re like a plate of steaming sarcasm—but the plate is really nice. Here’s everything that a modernist painting is supposed to have, as well: a surface with no illusion of depth to speak of and just enough figure-ground action to stop short of being a pure monochrome. The pours are good, because they make us think about the heroes of painting like Jackson Pollock, or the heroes of process art, like Linda Benglis.

But wait, something’s not right. It all looks a little too staged, like a neat emblem of improvisation and unruliness. Slater’s paintings appear cool, breezy almost, without a hint of anxiety, whereas we can taste the effort in Jones’ works, however much they may look like they were slapped together.

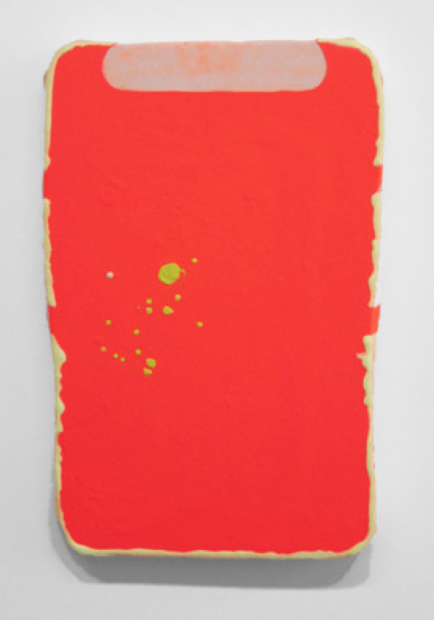

Bret Slater, Bad Moon rising, 2014. Acrylic on canvas, 59.6 x 38.7 x 2 cm

Jones and Slater both make paintings that seem to be a bit messed up. But Jones came first, so we can’t see Slater without also seeing Jones. And Jones and Slater talk to each other, so I wonder what they say. Imagine a conversation between their artworks, what a lot of attitude. Jones’ work says painting can be about anything made with the materials of painting, stripped down and going through its paces as stuff. It doesn’t have to look pretty or conform to any person’s idea of the destiny of art; it just has to be true to itself. What you see is what you see. Slater’s works say that too, but with a lighter approach. There’s a kind of freedom in both artists’ works, but Slater’s seem happier. His are nattering amulets, little painting-characters who want to tell us something. What are they whispering? I know: “We are from the future and we have come back to eat your copy of ‘Art and Culture.’”

Otis Jones, Black with 4 Circles, 2013. (Detail)

Jones’ paintings are objects, but there is nothing “specific” about them. They wear their history on their sleeve; I can see how they were made. And when I recall what came before them in the history of painting — slick, corporate, aloof, pristine painting — I can guess why they were made. Slater’s works, on the other hand, betoken a more peaceful setting. They slide in and out of my consciousness, flowing like the viscous pours that some of them are made of. I like both sensations: the hard, scruffy honesty of Jones and the intense, giddy menace of Slater. This is an exhibition of intimate entanglement; each affect would be poorer without the other. Just like the work of Jones and Slater, only more so.

Otis Jones + Bret Slater is on view at Holly Johnson Gallery in Dallas through July 28, 2014

7 comments

It’s nice to know there’s something in the work for the unwashed adrift in their “field of illusions.”

This is a nice looking show, very decorative.

I loved this review, Michael – it was written like you were one of the old phone operators at the exchange – to continue your theme – listening in on a conversation between two sets of paintings. I’m imagining a painting wearing a pair of tinted glasses and a set of headphones. “Go ahead, caller….” etc, etc Very nice to read such a well articulated review!

I like both Bret Slater’s work and Michael Corris’ writing, but it should have been noted that Corris is Chair of the Division of Art at SMU, where Slater received his M.F.A. in 2011. Isn’t that kind of thing supposed to be disclosed? Or is that just me?

It doesn’t really matter; it’s cheerleading, but that’s okay here and ultimately just irrelevant. More to the point though, the ‘conversation’ is depressing and so is the PR. It’s just boring style and their loop of influence strategy is too weak to go very far. That’s okay too. As you point out, close friends with some clout will play along for a bit and then even that support will erode. It happens a lot.

Stuckism is the quest for authenticity. By removing the mask of cleverness and admitting where we are, the Stuckist allows him/herself uncensored expression.

Painting is the medium of self-discovery. It engages the person fully with a process of action, emotion, thought and vision, revealing all of these with intimate and unforgiving breadth and detail.

Stuckism proposes a model of art which is holistic. It is a meeting of the conscious and unconscious, thought and emotion, spiritual and material, private and public. Modernism is a school of fragmentation — one aspect of art is isolated and exaggerated to detriment of the whole. This is a fundamental distortion of the human experience and perpetrates an egocentric lie.

Artists who don’t paint aren’t artists.

Art that has to be in a gallery to be art isn’t art.

The Stuckist paints pictures because painting pictures is what matters.

The Stuckist is not mesmerised by the glittering prizes, but is wholeheartedly engaged in the process of painting. Success to the Stuckist is to get out of bed in the morning and paint.

It is the Stuckist’s duty to explore his/her neurosis and innocence through the making of paintings and displaying them in public, thereby enriching society by giving shared form to individual experience and an individual form to shared experience.

The Stuckist is not a career artist but rather an amateur (amare, Latin, to love) who takes risks on the canvas rather than hiding behind ready-made objects (e.g. a dead sheep). The amateur, far from being second to the professional, is at the forefront of experimentation, unencumbered by the need to be seen as infallible. Leaps of human endeavour are made by the intrepid individual, because he/she does not have to protect their status. Unlike the professional, the Stuckist is not afraid to fail.

Painting is mysterious. It creates worlds within worlds, giving access to the unseen psychological realities that we inhabit. The results are radically different from the materials employed. An existing object (e.g. a dead sheep) blocks access to the inner world and can only remain part of the physical world it inhabits, be it moorland or gallery. Ready-made art is a polemic of materialism.

Post Modernism, in its adolescent attempt to ape the clever and witty in modern art, has shown itself to be lost in a cul-de-sac of idiocy. What was once a searching and provocative process (as Dadaism) has given way to trite cleverness for commercial exploitation. The Stuckist calls for an art that is alive with all aspects of human experience; dares to communicate its ideas in primeval pigment; and possibly experiences itself as not at all clever!

Against the jingoism of Brit Art and the ego-artist. Stuckism is an international non-movement.

Stuckism is anti ‘ism’. Stuckism doesn’t become an ‘ism’ because Stuckism is not Stuckism, it is stuck!

Brit Art, in being sponsored by Saachis, main stream conservatism and the Labour government, makes a mockery of its claim to be subversive or avant-garde.

The ego-artist’s constant striving for public recognition results in a constant fear of failure. The Stuckist risks failure wilfully and mindfully by daring to transmute his/her ideas through the realms of painting. Whereas the ego-artist’s fear of failure inevitably brings about an underlying self-loathing, the failures that the Stuckist encounters engage him/her in a deepening process which leads to the understanding of the futility of all striving. The Stuckist doesn’t strive — which is to avoid who and where you are — the Stuckist engages with the moment.

The Stuckist gives up the laborious task of playing games of novelty, shock and gimmick. The Stuckist neither looks backwards nor forwards but is engaged with the study of the human condition. The Stuckists champion process over cleverness, realism over abstraction, content over void, humour over wittiness and painting over smugness.

If it is the conceptualist’s wish to always be clever, then it is the Stuckist’s duty to always be wrong.

The Stuckist is opposed to the sterility of the white wall gallery system and calls for exhibitions to be held in homes and musty museums, with access to sofas, tables, chairs and cups of tea. The surroundings in which art is experienced (rather than viewed) should not be artificial and vacuous.

Crimes of education: instead of promoting the advancement of personal expression through appropriate art processes and thereby enriching society, the art school system has become a slick bureaucracy, whose primary motivation is financial. The Stuckists call for an open policy of admission to all art schools based on the individual’s work regardless of his/her academic record, or so-called lack of it.

We further call for the policy of entrapping rich and untalented students from at home and abroad to be halted forthwith.

We also demand that all college buildings be available for adult education and recreational use of the indigenous population of the respective catchment area. If a school or college is unable to offer benefits to the community it is guesting in, then it has no right to be tolerated.

Stuckism embraces all that it denounces. We only denounce that which stops at the starting point — Stuckism starts at the stopping point!

This is The Stuckist Manifesto, by Billy Childish and Charles Thomson, 1999.