Artists quote each other all the time, by way of homage, allusion, reference, rhyme and so forth, and have been doing so forever. But sometimes, especially in more recent times, such quoting gets raised up a notch into something qualitatively different, a fresh gambit (featuring a virtually one-to-one transposition) whose resultant works tend to get grouped together under the rubric “appropriation.”

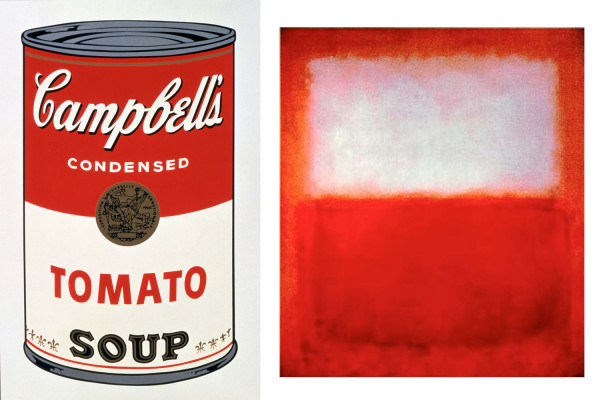

For example, Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup can paintings were just blown up renditions of regular Campbell’s Soup cans—though, granted, they played all sorts of riffs on contemporary artistic practice, for instance offering a sly, straight-faced Pop commentary on the transcendent aspirations claimed for the stacked color clouds of Rothko’s high mid-period, immediately prior. (Dave Hickey recalls how he once asked Warhol just what exactly the difference was between a soup can and a Rothko, to which Andy, typically unfazed, immediately replied, “That’s easy: Mr. Campbell signs his on the front.”)

And as a group, Warhol’s entire series of 32 soup flavors mounted along a gallery wall offered a tongue-in-cheek contribution to the then-recent fad for serial and grid production. Still and all, the disparity in size between can and canvas might undercut the strictly appropriational claims of the exercise, and for those thus bothered, Warhol offered exact size wooden boxes meticulously painted over with the red-white-and-blue Brillo pad insignia.

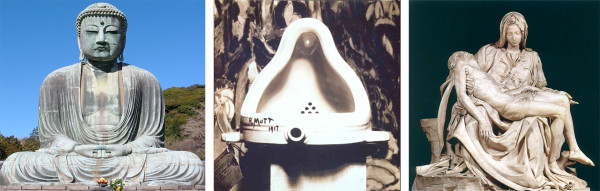

Now of course, in broaching such appropriative gambits, Warhol was himself appropriating one of the core methodologies of the inventor of appropriation, Marcel Duchamp. In 1917, or so the story goes, Duchamp, flanked by his pals Joseph Stella and Walter Arensberg, marched into the J.L. Mott Ironworks on Fifth Avenue in New York City, where he bought a standard Bedforshire model urinal, thereupon lugging the thing back to his studio, where he set the so-called ready-made on its side, signed it “R. Mutt” (“Mott was too close so I altered it to Mutt, after the daily cartoon strip ‘Mutt and Jeff,'” he later said), titled it Fountain, deemed his day’s labor good and declared the object “art.” (There’s an alternative version of the piece’s genesis that has Duchamp himself appropriating both the gesture and the very object itself from a “female friend” who supposedly had sent it to him—speculation centers on the scatalogically inclined Dadaist Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven—but we’ll set such revisionist conjecture to the side for the time being.) At any rate, Duchamp now endeavored to enter the piece into that spring’s follow-on exhibition to the Armory Show of a few years earlier, where his Nude Descending a Staircase had caused such a howling critical ruckus (“an explosion in a shingle factory”). This time, though, the show’s scandalized organizers didn’t even let the piece—after all, simply a urinal set on its side—into the exhibition.

Simply a urinal set on its side, yes, and yet much, much more. “A lovely form has been revealed, freed from its functional purposes,” as Duchamp’s sidekick Arensberg insisted, appealing the board’s decision, “—therefore a man has clearly made an aesthetic contribution.” (An estimation resoundingly reaffirmed, almost a century later, when over 500 international art experts voted it “the most influential modern art work of all time” in a poll as part of the run-up to the 2004 Turner Prize.) But such acclaim was a long way away in 1917. So Arensberg and Duchamp carted the forlorn thing over to Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 Gallery, where Stieglitz photographed it in a glow of profound reverence. Carl Van Vechten subsequently enthused to Gertrude Stein, by letter, how “the photographs make it look like anything from a Madonna to a Buddha.” Or, as I myself always thought, and, interestingly, found myself thinking again recently: a Pietà.

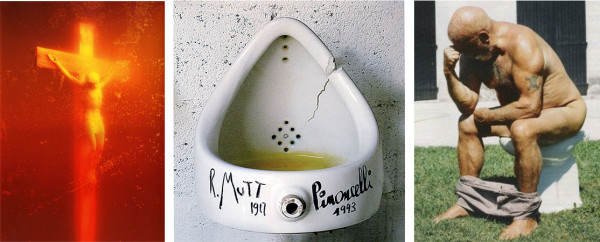

For, a few years back (in January 2006, as followers of my Convergences Contest column on the McSweeneys website may recall), a 77-year-old “art activist pensioner” named Pierre Pinoncelli from Saint-Rémy-de-Provence (site, as it happens, of Van Gogh’s famous asylum) attacked Duchamp’s signature icon Fountain with a hammer, slightly chipping it, as it lay in state as the centerpiece to the Pompidou Center’s massive Dada retrospective in Paris. Many shocked news readers the next morning (I am sure, at any rate, that I was not alone) were put in mind of that infamous moment, back in May 1972, when an Australian geologist named Laszlo Toth, ecstatically keening “I am Jesus Christ!,” took a hammer to Michelangelo’s sublime Pietà in the Vatican, causing considerable damage. While Toth was being almost universally decried as a cultural terrorist, a small band of radicals took to hailing his “gentle hammer” under the distinctly more Dadaist slogan “No more masterpieces!” Toth was eventually committed to an Italian asylum and then expelled from the country, and even though the sculpture was presently repaired, the attack left quite an impression.

(A few months later, the National Lampoon ran a photo of the attack itself, Toth’s hammer-wielding arm raised in ecstasy, under the memorable caption “Oh my God, Pietà? I thought it said Piñata!” And some years after that, perhaps similarly liberated—or, alternatively, deranged—by the incident and its Duchampian precursor, Andres Serrano perpetrated his own Piss Christ, a hauntingly luminous—albeit utterly scandalous—photograph of a plastic crucifix suspended in a glass of the artist’s own urine.)

Delighted at his own good works, Pinoncelli (the Fountain vandal) retired to his St Remy redoubt to await trial, passing the time by posing outside, naked, in a Rodin’s Thinker clench, perched atop a toilet. As things developed at said trial, it turned out that this had not been Pinoncelli’s first attack on Duchamp’s masterpiece. Back in 1993, in what may count as the single most inspired feat of performance art of all time, Pinoncelli had urinated into the sculpture as it lay on display down the road in Nîmes, France. At the time, he defended his action, explaining how he’d simply been trying to “give dignity back to the object, a victim of distortion of its use, even its personality.” This time around, he amplified that exegesis by explaining to reporters how, “having been transformed back into a simple object for pissing into after having been the most famous object in the history of art, its existence was broken, it was going to have a miserable existence… Better to put an end to it with a few blows of the hammer,” he went on modestly, esteeming his own gesture “not at all the act of a vandal, more a charitable act.”

Ah, the Resurrection and the Life of Art!

Which brings us to the most recent iteration of this discourse, for just this morning I got an email from the New York-based Russian exile post-pop post-dadaist master Alex Melamid.

![Alex Melamid [via New York Times]](https://glasstire.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/JPMELAMID1-articleLarge.jpg?x88956)

Alex Melamid [via New York Times]

Art calls for reverence. We, the cultured, venerate art.

We believe unequivocally that art gives us the best in the spiritual domain, soothes souls and opens channels to the unspoken and unspeakable.

Good gracious!

Moreover, it gives a chance to make tons of money, do away with office slavery, and be rewarded with artistic license.

Sounds great!

So every year thousands upon thousands of young men and women flock to art schools in pursuit of a dream and a buck.

God bless them!

But as we all know, most of the dreamers will be awakened at the certain age by the harsh reality of crashed dreams, lost opportunities, moneyless future, and lack of any marketable skills.

Too bad!

With that by way of rationale, he went on to announce that he and Phillip Gulley were therefore launching “The Institute of Responsible Re-education, for fledgling students in New York City,” going on to lay out their intention to teach marketable skills “to the people of relatively low IQ and proclivities for tinkering—the type of individuals from which most artists are recruited.” They intended, he continued, to offer “certification certificates” in such trades as “administrative assisting, appliance repair…child day care…funeral service…gunsmithing…message therapy…pet grooming, plumbing…and travel & tourism.” The students would begin their studies by being subjected to a “Three Steps Art Detoxification Program, or Art Rehab, at our facilities in New York City.”

But—and here’s the point—for their graduation thesis, in order to display their new-won vocational competence, “students will be required to connect a urinal to the sewer of the Art Gallery. By that, Modern Art that originated in the Pissoir of Marcel Duchamp will be re-connected to the sewage system of a great city.

“Good riddance,” opines Magus Melamid, by way of conclusion.

POSTSCRIPT

Wonders never cease: certainly so, at any rate, when it comes to Duchamp’s Fountain. No sooner had I finished this piece than friends (aware of my slight obsession on this subject) sent me two separate dispatches. The first consisted in a Tumblr sighting of what may be the one of the greatest impromptu site-specific pieces of graffiti of all time, to wit:

And the second documented the artist Antonia Marsh’s contribution to the recent Last Brucentennial, in New York City (a group exhibition of work by 600 women artists):

UPDATE 6/2/14: And this just in, the latest from Grand Master Melamid:

Lawrence Weschler is the author of numerous books, including Mr. Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonder and Uncanny Valley: Adventures in the Narrative, as well as Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees, the seminal book about the artist Robert Irwin.

6 comments

Dear Lawrence, thank you for a most stimulating essay about Duchampian shenanigans sans adoration. Duchamp’s ultimate goal was to destroy art as he knew it, and probably as we know it. In the process art exploded in possibilities and did survive nihilism. However, one must point out by the kind of factual description you undertook in the essay, that certain artistic gestures maybe be anecdotal at best, generally trivial, or simply daft.

We met a few years back. Do stay in touch.

Fernando Castro R.

At first I was turned off by the blatant “art talk.” (Why do we do this?) But then, was so delighted by all the many historical extras provided (many laughs) I was glad I continued reading.

This was great fun to read, and full of layers. One thing that comes to mind, when learning about the original purchase (with Joseph Stella and Walter Arensberg at Duchamp’s side), is that the existing Fountains are said to be replicas! Replicas of a readymade…Note this label from the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Label:

Fountain is among the most infamous artworks of the twentieth century. Yet, the original was lost shortly after it was submitted to the Society of Independent Artists’ first exhibition in April 1917 and rejected by the hanging committee. The work became known later as an icon of New York Dada primarily through replicas, which Duchamp created first in miniature for his Box in a Valise (1935–41, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1950-134-934). Then in 1950, for the exhibition Challenge and Defy at the Sidney Janis Gallery, he authorized Janis to purchase this urinal secondhand in Paris and added his original inscription. This was the version of Fountain seen by Cage, Rauschenberg, and many others in exhibitions throughout the 1950s and 1960s.

Thanks for pointing this out – this fact is almost always looked over in Readymade discussions. It is true – the readymades that we see today are almost always not the originals. The largest (by far) batch of readymade replicas was made in 1964 by Arturo Schwarz’s gallery in Milan. They made replicas of 12 different readymades in editions of 8 – all at once! Anyways – here is a link to a show that is up right now at the Gagosian – the replicas are all being shown together. http://www.gagosian.com/exhibitions/marcel-duchamp–june-26-2014

Enjoyed the read, but isn’t that last image an homage to René Magritte?

Of course. I think it fits here to make a connection between Magritte’s philosophy of illusion and the critiques that Duchamp and Warhol were leveling against culture, art and commoditization. “The Treachery of Images” is to remind us that representations are not reality and, in the broader context of Magritte’s work, that our perceptions are not necessarily reality, either. Duchamp and Warhol aimed to dismantle the presumptions of art and remind viewers not to take it too seriously. At least, I consider those ideas corollary.