While working on a “serious” review of the current Magritte exhibition at the Menil, I fell into an Internet wormhole. Via Google images I had stumbled onto a site called dhgate.com selling wholesale mascot costumes out of China. Before I knew it, I had 50 tabs open and no idea what led to what. The site is full of smiling mascots standing on a scraps of cardboard and welcoming you to a cluttered desolate office or a bleak warehouse. The images are sad clown tragic/funny.

It was a moment of accidental surrealism, an encounter with the “”mystery of the ordinary,” to steal the Menil exhibition’s title. The Internet had collapsed the distance between me and a far off place, providing a completely disjunctive experience. The mascot images also have hallmark “surreal” characteristics: their cartoon subject matter is juxtaposed against their bleak surroundings, and they contain something hidden/unknowable because of the mascot’s disguise. They are also unintentionally overlaid with text and often in confined spaces (offices, etc.), a superficial similarity to some of Magritte’s work.

Granted, these images are not made with the same self-conscious psychological and philosophical considerations as a Magritte, but they make me wonder where and how Magritte lingers in the world today. In her excellent talk at the Menil, scholar Sarah Whitfield, (who would probably be horrified by my mascot/Magritte association) talked about the sources of Magritte’s imagery in his personal experiences. Looming large was his recollection of an encounter with a painter in a cemetery; his paintings are full of funerary objects and references. His mother’s suicide in a river put Magritte’s desolate seascapes and rivers in a new context. Whitfield related his brother Paul’s confinement when his mother was locked inside their home (because of her previous suicide attempts) to Magritte’s interior spaces where objects of exaggerated scale may feel trapped. Whitfield explained how Magritte made small stage sets out of paper as a child and how his images mimicked these constructions, full of silent drama and Magritte’s personal anxieties and preoccupations surrounding death.

René Magritte, L’assassin menacé (The Menaced Assassin), 1927, Museum of Modern Art, New York. Kay Sage Tanguy Fund. © Charly Herscovici – ADAGP – ARS, 2014

The Mystery of the Ordinary: 1926-1938 looks at his early work to show how Magritte develops his brand of surrealism. There is plenty of iconic Magritte—clouds, bowler hats, and the famous “not-a-pipe”—but there is also a darker, violent strain that runs throughout his earliest work. The exhibition opens with a theatrical murder scene. In The Menaced Assassin, 1927. a nude woman’s dead body lies with blood seeping from her mouth. The painting hints at many of Magritte’s forthcoming preoccupations: the act of looking, framing, and an image’s representational link to reality or truth.

The Menaced Assassin is like many of the early Magrittes on view, ominous yet also slightly cartoonish. It shows a 28-year-old Magritte in his early stages where he is definitely not a virtuoso painter. His figures are flat, slightly clunky with fairly simple modeling. His paint handling becomes more refined in later works done in 1954-1967, also on view at the Menil, but praising or criticizing Magritte for his level of technical skill misses the point. Despite the surreal label, his images are not supposed to have a realistic presence, but simply a representative function.

In the early, more sinister images, Magritte deals with issues like sexuality and violence. Entracte, 1927, is full of arms and legs fused together in sinewy shapes set on a minimal stage like a grotesque play. In The Meaning of Night (pictured below), an anonymous man in a bowler hat stands on a beach with his eyes closed. His face is masklike and his body is mirrored to show his back or to suggest his double. A floating, gloved hand pulls at an abstract suggestion of a woman’s lacy undergarments and stocking covered legs. It could be presumed that this fantasy landscape with this lewd scene is alluding to the bowler-hatted man’s internal psyche or his dreams when he closes his eyes.

Near The Menaced Assassin and The Meaning of Night is a vitrine displaying advertisements Magritte did at the time for an art studio, a jeweler, and a fashion designer, among other clients –ephemera such as this are mixed in throughout the exhibition with photographs, surrealist journals, etc. These illustrations reinforce that Magritte was not as much a painter as an image-maker, who I imagine would have felt at ease with whatever technological means of representation most interested him at the time. Magritte asked Andre Breton to correct Max Ernst’s characterization of his paintings as “collages entirely painted by hand,” but the statement feels fairly apt.

In her talk, Sarah Whitfield quoted Magritte’s basic intention to make paintings with a “disturbing poetic effect.” But if Magritte achieves his goal to disturb and discomfort the viewer, why is he so immensely popular? Other artists of equal and more profound poetic effect do not necessarily extend into popular culture so easily, and in the art world you are informally taught a kind of surrealist hierarchy that often corresponds to each artist’s mass appeal: Max Ernst, good; Magritte, OK; Dali, bad. Magritte’s images do translate well in reproductions, and his techniques of collaged juxtapositions and shifts of scale seem made for our Photoshop age where image editing is so easy.

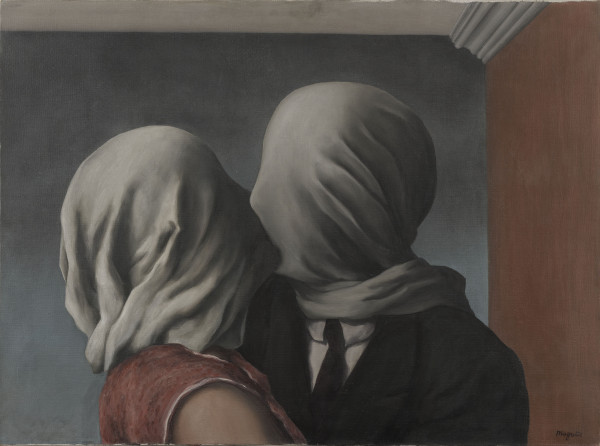

Magritte’s own images have been “remixed,” parodied, and appropriated as they have cemented themselves as icons in contemporary visual culture. While procrastinating on my “serious” review, I have gotten lost in Google images of Magritte halloween costumes and the hundreds of images with a #magritte on Tumblr. Even Beyoncé quoted The Lovers painting in a recent video.

René Magritte, Les amants (The Lovers), 1928, Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard S. Zeisler. © Charly Herscovici -– ADAGP – ARS, 2014

A still from Beyonce’s “Mine“

Via tumblr

Super-Magritte. More examples here

These images show the fandom surrounding Magritte, and high art investigations have been done to show how Magritte has influenced contemporary artists like Richard Artschwager, John Baldessari, Vija Celmins, Robert Gober, Jasper Johns, Jeff Koons, Ed Ruscha, and Andy Warhol. The Menil exhibition has work by Celmins and Warhol just outside the galleries to show this connection. Magritte’s influence on artists and popular culture is undeniable, but also makes his imagery much less shocking. His strategies are well-worn at this point. Elements of his earlier work surprised me, but I am still searching for the answer as to why his lasting power and imagery is so pervasive. For me, the mystery is how Magritte became so ordinary.