Ricky Yanas’ works in Historical Present, on view at the UT Austin’s John L. Warfield Center for African and African American Studies, re-presents the iconographies of 1960s-1980s resistance movements, mined from university and city archives and speculates about their use in the past, present, and future. I spoke with Ricky about how his project developed and how this imagery resonates today.

Lauren Moya Ford: The images in the exhibition are so pared down and clean they resemble brands. Why?

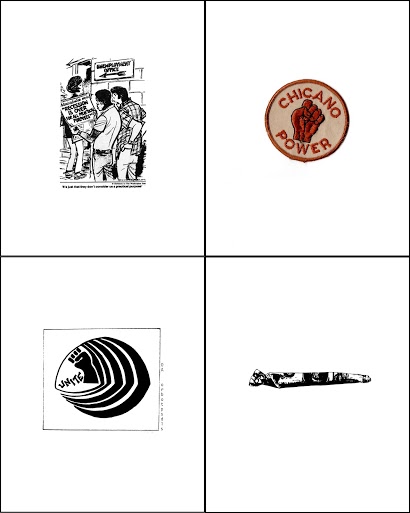

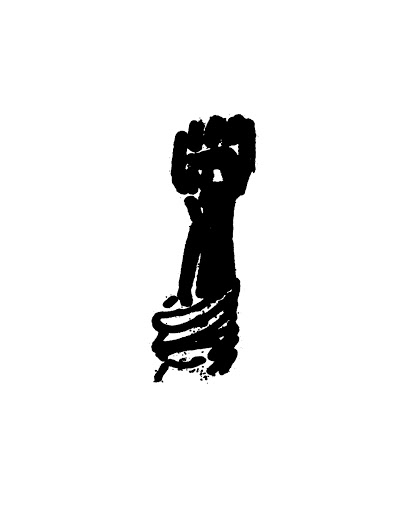

Ricky Yanas: For clarity. I wanted the viewer to be enamored with the historical charge, the nuance of the icons, and pertinent ideologies—not so much my process. I took the scans and digital photographs I shot, boosted the contrast, and eliminated all but the symbol. This turns the image into a direct link to the idea and not necessarily its physical referent.

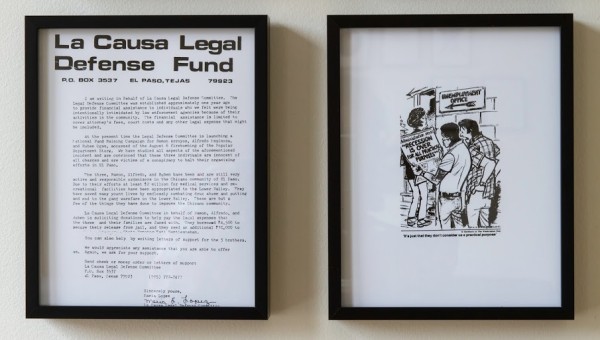

LMF: The photographs of archival documents are legible and printed on a surface that is about the same size as a sheet of paper. They are experienced as texts to be read and as images to be seen at the same time. How do literature and theory inform your project?

RY: New influences are constantly emerging. A plethora of social theorists and artists have played important roles in my current work. Noam Chomsky is a major one. His books and lectures on the American media made me understand that even NPR only reports on symptoms and not the larger contexts of socio-political problems; the format of its programing rarely allows for the in-depth research necessary to understand the subjects it’s reporting on. That the general public never truly receives the historical context of events taking place in the world and here in the US creates a frightened and alienated populous. It also creates cynical artists.

When I began working at Texas State University in San Marcos, the drive back and forth was draining, but I realized I could use the time to learn. I listened to artists speaking about their work; Marcel Duchamp, Adrian Piper, Mike Kelley and Tupac Shakur speak so clearly about their intentions. Eventually I found a talk by Black Panther Aaron Dixon, sharing the history of the organization. This revealed to me how completely wrong the general point of view on the Black Panther party is. Listening to their figureheads speak (Huey Newton, Rap Brown, Bobby Seale, etc.), I came to understand that these people were intellectuals and powerful orators, charged with discontent, speaking against social injustice and against racism, demanding black control of their peoples’ destinies. They were unbelievably brave. Fucking inspiring stuff.

LMF: Where did the idea of working from the archives come from?

LMF: Where did the idea of working from the archives come from?

RY: All this was taking place at a time when Rose [Salseda, the exhibition’s curator] and I were talking about our shared interests in minimalism and American radical movements. Rose offered me the opportunity to show alongside Juan Capistran, whose work incorporates icons and figures of the Black Power Movement and who was scheduled to show at the Warfield Center. So I took the chance to describe similar radical impulses which, at one time, bubbled so fervently in Austin.

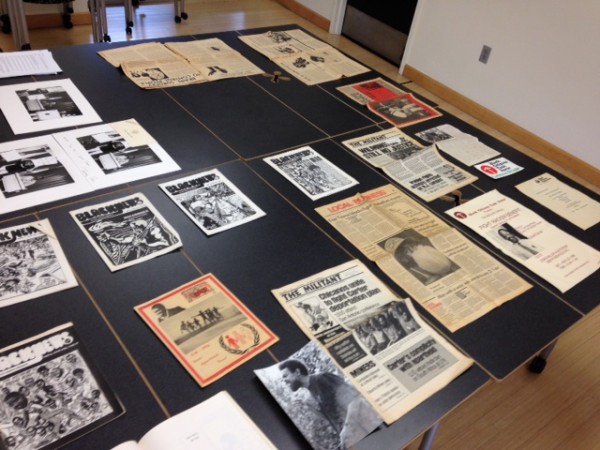

Rose suggested I start with the Warfield Center’s own archive (pictured above) and I began grabbing newspapers and images that resonated with the talks I had been listening to. Many were alternative publications printed throughout the 1970s and 1980s here in Austin including The Militant and The Villager. From there, Rose pointed me in the direction of the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, the Benson Latin American Collection, and the Austin History Center. At one point, Gloria Espitia from the Austin History Center brought me an entire cart of newspapers from this period in Austin! In the end, I think the images I produced resemble a Xerox copy, just enough reproduction to get the info across.

LMF: Recontexualizing and rearranging these archival materials open them up to other meanings. How does the location of the exhibition affect the audience/reception of the work?

RY: The Warfield Center’s focus is to facilitate “research that is dedicated to the intellectual, political, artistic, and social development of people of African descent in the African Diaspora as well as the African continent.” In each arrangement on the walls, I wanted to make relationships between black and brown struggles, between capitalism and racism, between national problems and local action. The installation’s minimalist grid offered a way of working against the utilitarian aesthetics of the space and provides an authoritative structure that not only connects with art history, but also makes the imagery seem fresh and new—“contemporary.” The images do not hang passively on the wall; they pronounce themselves as art and information.

The Warfield Center holds offices, study areas, and class meetings. For me, exhibiting there rang as an opportunity that the traditional gallery setting does not allow. It’s a slower space, where the opening and the art crowd do not create its value. People, not art people, have to live with the work. It is my hope that a frequent visitor to the space or someone who has an office there might investigate the content further, over time.

LMF: So, part of the installation’s success has to do with the viewer spending time with it, taking up elements of the investigation that you initiated. Is this experience something that cannot happen inside a gallery or museum?

RY: It can but rarely ever does. I have experienced artworks where people stay for hours reading and engaged with the content of a work. Italian artist Stefano Arienti’s installation for his 2007 residency at Artpace in San Antonio is a great example. But the typical visitor to a gallery or museum views the works at the opening or in a single visit, spending no more than a couple of minutes with each piece and moving on, never to return. I am no different.

The works in the Warfield operate differently. They are not so much for the customary gallery goers or museum patrons but for the people that use the space daily. They have a captive audience and the ideas that they present are undeniably relevant to the the Warfield’s particular history as well as the charged political field beyond its walls.

LMF: The work evidences a tension between documentation of the past, representation of the images’ current state, and a projection to something contemporary or future. Where does your interest in this play on time come from?

RY: I am very much influenced by the Situationist International, a group of European writers and artists organized in the late 50s and active until 1972. Helmed by writer/filmmaker Guy Debord, the group engaged art and art making with a Marxist/anarchist perspective and was more concerned with individual activity rather than an allegiance to a particular style or manifesto.

Dérive and détournement were their primary modes of action. Dérive is a kind of critical wondering session—a process of active reception—where an individual or group travels through the city assessing how it pushes and pulls a person through space. Détournement was acting on what you have learned—taking artwork and reworking it, negating it, taking the world and playing with it—what we might call appropriation today. What I love so much about the group is that each individual made work in their own way.

Their efforts focused on re-affirming art by rejecting its institutionalization. By remaking or reworking older artworks, they attempted to make them current and use their power to create a dialogue with the now. Their ideas still seem so fresh to me—seeing art as action rather than the fine object which must be preserved. Here is a video:

In a process of détournement, I worked with the Briscoe, Benson, Warfield, and Austin History Center archives, but instead of negation I wanted to reactivate the material. By bringing these images and ideas to the present, the viewer is able to engage with a time when people saw political action as a tangible thing. Like the Situationists, I am using these older icons/symbols towards not purely historical ends; I am trying to pull them out of their archival mausoleums to mobilize them in people’s minds. Since they are sharpened, isolated, and detached from their specific historical contexts, I get people asking me: “When were these made?” This information does not become clear until they see the finding guides (which list the provenance of each item). But it’s that tension, that suspended moment, between the past and the present, the present and the future, that is so exciting to me.

Historical Present is curated by Rose G. Salseda and features works by Ricky Yanas and Juan Capistran. It is on view until May 13th at the ISESE Gallery at the John L. Warfield Center for African and African American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin, 201 East 21st Street, Jester Center A230.

Ricky Yanas (b. 1984, San Antonio, Texas) is an Austin-based artist and photography lecturer at the Texas State University, San Marcos. Since graduating from the MFA program in photography at UT Austin in 2011, Yanas’ work has been featured in exhibitions at Mexic-Arte Museum and Up Collective in Austin. In 2012, he was a co-recipient of the Idea Fund Grant and a guest editor and featured artist in Pastelegram, an Austin/ Los Angeles based print and online art magazine.

1 comment

“I am very much influenced by the Situationist International” – what recently art schooled human isn’t? May as well be “vintage” and “retro” and claim influence from Relational Aesthetics, wear flannel shirts, and listen to Pearl Jam. Now THAT would be so american cool.