House Plant 1

The name is the show: eight big, glossy potted houseplants, photographed against blank white backgrounds. Ostentatiously unremarkable, Michael Mazurek‘s smart plant portraits at Conduit Gallery in Dallas are like houseplants themselves: designed to disappear.

Authorship, in photographs, isn’t self-evident; the brain behind the camera can be hidden from the viewer behind layers of technology, and Mazurek is in full stealth mode. Each choice, whether of subject, lighting, background, or framing, is as near the default as possible. Eliot Porter, he’s not: Mazurek’s photos eschew dramatic techniques that could make his plants more vivid than real life. As-is, they’re healthy, but not perfect. Big, but not too big. Pleasant, but not ravishing.

Mazurek effaces himself from his images, leaving them so purposefully generic they simulate the effect of houseplants better than actual plants would: a show of real plants, as art, would have been too exciting: more sensually pleasing and more confrontational, and Mazurek wants neither.

House Plant 2

Why? Many artists, externalizing their discomfort with the reality of art’s end-use as decor, have produced intentionally bland, pleasant objects with greater or lesser admixtures of irony; Mazurek’s plant pictures are mid-range: the plants are presented without bitter sarcasm, but their clinical objectivity prevents them from being entirely cozy. The plants are shown in a variety of plain plastic sales pots- corrugated black, terra cotta, green and white, as if Mazurek went to a garden center and chose a cartload of models for his project. They’re emphatically not beloved family members, and their isolation echoes the familiar blend of cheeriness and alienation we experience in schools and businesses every day. The plants look a little lonely in all that whiteness.

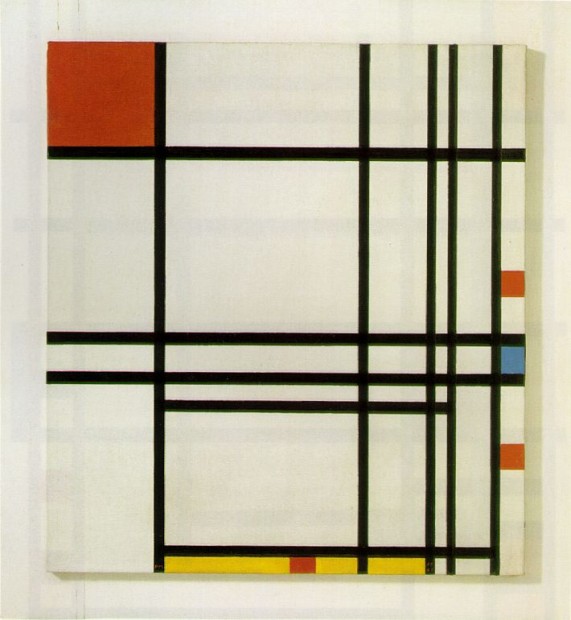

Piet Mondrian, Composition Number 8

As companions, houseplants rank just below goldfish in terms of their demands for care and their return of love. Mazurek’s photographs are one rung lower. Fusspots with a strong emotional conviction that art must be expressive, or personal, or tell a good story might find Mazurek’s House Plants upsetting, but the same can be said of Mondrian. Plants are nice. Squares are nice. Mazurek’s plants reiterate the oft-heard critique of abstract art: it is complicit, by aloofness, in whatever cultural skullduggery is afoot. These vegetables protest their innocence too strongly: obviously, they’re hiding something.

House Plant 4

Superficially, Mazurek’s plants recall the work of San Antonio artist Chuck Ramirez, who also used digital imaging skills drawn from commercial photography to present commonplace objects. Ramirez’s series on discarded hospital flowers, opened suitcases and bags of trash all used deadpan documentary to present ordinary things emphatically, so that their implications were forced into the viewer’s consciousness. Ramirez’s studies showed that, despite their interesting particulars, in experiences like discarding trash, packing a suitcase, and even dying, we are more alike than different. Mazurek, a social critic, is less interested in people than in issues.

Chuck Ramirez, Trash Bag Series: Vegan

Six of the photos are of unique plants, each a different species, but in House Plants 5 and 3 the same plant is photographed from different angles, in different pots, and printed in two different sizes, but isn’t fooling anyone. It’s the same plant. Anyone who looks can see it.

House Plant 3 and House Plant 5

But who’s going to look? Everybody, because there’s nothing else to look at. The duplicate plant turns the exhibition into a bizarre exercise in forensic plant identification. Comparing telltale nicks on leaves, I looked at Mazurek’s photographs much more carefully than I would have looked at real plants. The photographs are larger, they’re well lit and mounted at eye level and, in a gallery, you’re supposed to look at the art. Only as I turned away to type this article did I notice the real-life orchid on the reception desk, next to my computer.

Michael Mazurek: House Plants will be on view at Conduit Gallery in Dallas through February 15, 2014.

5 comments

Nice but a bit boring to my taste. Centering each shot and having pots make these pics look like they were shot for mail order catalog.

Another possible perspective might be that these are pictures that are deeply conservative, typical of the sort that inevitably claim space on the walls of the middle-guard Texas spaces. The assertion that these are stealth gestures is false, rather they are wholly recuperated strategies and therefore, at the very least, suspect. The exhibition, overall, is competent (yay) but the claims here are overreaching. The writer picks up on the legible cues and attempts to fake-mystify the images and then match them to some of the weaker positions that continue to occupy his mind as editor. There’s so much challenging new work to decipher and thoughtful, provocative art writing all over the web. GT becomes even more frustrating this year, as it insists on addressing work and presenting critical perspectives that often simply re-pose questions otherwise resolved many decades ago. Why.

From a fusspot’s perspective it seems the distance is what makes these interesting in the author’s mind. Why bother going to the exhibition? The context can be fairly imagined. It’s also evident that it isn’t the artist’s product discomfort on display – as usual – but that of the patron. A proudly worn itch never dared scratched or an off-kilter yet serviceable cog. Moreover, the comparison with Mondrian is stretching the limit, if only for reasons of medium. There are pared-down vocabularies and then those that begin and end with nothing. How long and how many times will it be interesting and laudable? You fought hard (too hard?)but I don’t buy it. This is just another example of how much privilege it takes to enjoy poverty. Artists will never get away from the fact that sensation is the only socially relevant tool they wield – as much as they might want to be philosophers.

You’re totally right about not having to see it, but until I went, I wondered if there wasn’t something I was missing. I went to the exhibition so you don’t have to!

I don’t think it takes too much privilege to enjoy these- one of the nice things about the show is that these photos would be about as unexciting and innoculusly pleasant anywhere, for almost any audience. Putting them in a gallery and dissecting them as cultural critique doesn’t make much difference.

I think the Mondrian comparison is apt- when I used to take students to museums, Mondrian was always a hard sell, mainly because his paintings lacked things the kids expected in art. Mazurek’s plants do this, too. Except they’re not visually pared-down, they’re conceptually pared-down. It’s a big one-liner, on purpose.

I don’t know when your critical rope-a-dope begins and ends. I take it I can visit a dentist’s waiting room and have a similar experience … innocuous, but not pleasant. I would reserve pleasant for the experiential. But I’m not adverse to the pleasant.

No matter the poverty (and they are as well formally impoverished) It does take a unique amount of intellectual largess, if not acrobatics, to consider such skinflint givings so seriously. Wasting good prose on a ‘huh.’ But thanks for the response.