Michael Mazurek is a conceptual artist who juxtaposes familiar images and objects to raise them into symbols. For his new, self-titled show, he examines themes of masculinity, and what he calls “the fetishization of the desirable and identity.” The principal image is obvious: Cocks.

The rooster is a loner. There is something prehistoric in the thoughtless eyes, weird musculature and baseness in its drives: fertilize; eat; defend. It looks violent and funny at the same time. It’s feathers are motley and its crow is an alarm. The bird is sometimes portrayed as a harbinger or trickster—an odd, aggressive thing that factors into a change of fortune.

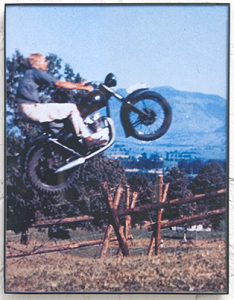

Another key image in the show is the late actor Steve McQueen. He portrayed a more subtle form of aggression—tense, not fancy. McQueen’s most famous roles present him as a trickster, the outsider who possesses a wily intelligence.

Another key image in the show is the late actor Steve McQueen. He portrayed a more subtle form of aggression—tense, not fancy. McQueen’s most famous roles present him as a trickster, the outsider who possesses a wily intelligence.

Mazurek’s painting of Steve McQueen has a giggly way of undercutting the actor’s tense demeanor. This is bronze paint right out of the tube. The bronze body and shining head make a funny, heavy-handed rhyme with the bronze-age hero, Odysseus—another wily thinker, outsider, and adventurer.

Homeric heroes are fascinating in a present-day study of masculinity. They embody the violence of their world and a sort of forgiveness for it. McQueen’s characters are a bit Homeric, but a cool, loner attitude and need for speed is as far as the actor’s contribution goes to the culture. As the film historian David Thomson observes, “his characters were more interested in machines, or a boyish, incommunicable honor, than in other people.”

One doesn’t look to the McQueen sense of cool for how to navigate domestic life. Fittingly, the pictures in Mazurek’s exhibition show the actor alone. The cocks, too, stand (or strut or crow) alone. These rooster photographs have been cropped so that scarcely any background is visible; showing neither the cock’s environment nor its situation with hens. Stagnation is implied. Zero opportunity for fecundity. In this sense, the cocks look like figures in a cosmic joke. All that preening, strutting and crowing, signifying nothing.

Robust displays of productive potential that ultimately come to nothing are a recurrent theme in Mazurek’s work. Suplex Version 1, from a previous exhibition, describes a rough phase in the construction of a commercial shopping center and, alas, the unmaking of it, when the center fails. I’ve seen such failure all too often near my home over the last year: A Borders store and an apartment complex reduced to nothing; Blockbuster cleared out; a Tom Thumb Grocery gone. Suplex Version 1 is like an afterimage of commercial failure.

The opening images of the show, Steve McQueen and roosters, poke fun of the male stereotype with images that are part of that stereotype. This way of poking fun is also a comment on an annoying trend in postmodern art: trying to critique a society reliant upon commercial spectacle by using the tools of commercial spectacle. McQueen and the roosters act, in part, as a send up of what Mazurek calls in his statement “politicized and/or critique oriented work.” Fighting spectacle with spectacle proves to be a game of futility. Want to make a statement about large-scale marketing strategies that infantilize the culture? Then build a giant balloon dog out of polished steel (a la Jeff Koons). Want to protest a media-reliant scheme of Christianity that overlooks the body of the poor? Win publicity by dropping a crucifix into a glass of urine (a la Andres Serrano). Want to observe the loss of the memento mori reality to a reality of credit card debt ridiculously lengthened beyond mortal limits? Encrust a human skull with thick, twinkling diamonds (a la Damien Hirst).

The game of fighting spectacle with spectacle is neither illuminating nor transformative. It is only a surface response and lacks for subversive ideas that might upset the status quo and present alternative points of view. The famous pieces I described were never about being subversive, but rather they were built as commodities that traded on sarcasm—the fuss they raised somehow only heightened their favor in the status quo of the commercial market. Mazurek’s images of roosters and Steve McQueen in his self-titled show about masculinity make a layered and funny response to art that trades on distortions of scale rather than reflect on the artist’s state of mind.

A truly subversive work explores the status quo from underneath, seeking out some oddity for leverage, not to overturn the status quo, just upset it a little, to reveal alternative perspectives and make way for transformation. The difference between a subversive act and a revolutionary act is as different as the modes of C.G. Jung and Che Guevera. And a subversive work is not something you would think of as a commodity.

Although Mazurek’s critique of stereotypes and commercial spectacle at the beginning of the exhibition threatens to overmatch his other ideas, he saves the show with a modest but deeply personal set piece at the end. The show’s back chamber recasts the cock and McQueen images that came before.

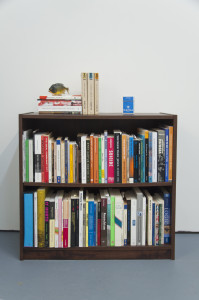

Mazurek has arranged the final room in the show with a desk, a bookshelf, and a board that describes his workout regimen. The vibe in the room suggests more a classical Greek gymnasium, where men gathered for exercise and relevant conversation, than it does your bro’s man cave.

The desk is cruddy, but clear: no photographs or nostalgic trinkets; no unfinished ideas stacked up. The books show signs of handling. Their subjects are social sciences, logic, and aesthetic studies. The workout regimen is impressive, but something a person can do alone, without a gym membership. Written lightly in pencil it’s a simple tally of personal achievement, not a graphic monument. This is an ascetic space for figuring things out.

Hints of classicism are all over Mazurek’s show. He is abstractly literary in that the symbolic elements (the crowing cock, the loner-hero, the authority of the desk) serve a fundamental narrative. The exhibition is a psychological mirror: a middle-aged man (Mazurek has just entered his forties) looks inward for a way to convert the preening, selfish courage of the past into a relevant, healthy, and thoughtful future that preserves the rebel and trickster aspects in a maturity marked by rigorous and prolific critical thinking.

The exhibition has oversights. The artist has designed a show about masculinity that doesn’t feature images of sex, domestic partnership, camaraderie, or generation. Another hurdle is Mazurek’s almost iconoclastic pursuit of a stripped-down documentary sort of purity. Visually decorative elements are, to him, unwanted distractions.

Mazurek has chosen to portray isolation over fecundity. The exhibition suggests his transformation into middle age is like a lone walk in the wilderness. In the event, he has reshaped a familiar psychological narrative, an individual’s journey into a vast and open landscape, leaving structure behind in a search for selfhood, but taking it out of its cosmic context and centering it instead in the mind of the artist.

I wish that Mazurek would press his anarchistic tendencies, his self-reliance, and worry less about stereotypes and follies in the art market. These concerns distract from an otherwise enviable drive to create meaningful symbols from the depths of everyday situations that also stand as subversive art.

Michael Mazurek runs through January 11, 2014 at Oliver Francis Gallery. Contact 1-817-879-8231 or [email protected] for an appointment.