Changing Things (detail), 1997. Silk, plastic, and wire, 76 x 148 in.

The first comprehensive survey of Jim Hodges’ art at the Dallas Museum of Art repeats a working paradigm: the artist habitually transforms artificial materials into reimagined visions of nature. The most obvious examples are Hodges’ well-known arrangements of silk and synthetic colored flowers, organized either directly onto walls, strung in sculptural vines from ceilings or anchored together in tapestry scrims implying the pull of gravity, like floral waterfalls. There is a simple elegance found in much of Hodges’ art, even as it veers towards a kind of lyrical sentimentalism—at times beautiful, but dangerously close to cliché. This willingness to approach the whirlpool of easy platitudes dedicates Hodges’ work to a kind of reverie uncommon in contemporary art.

With the Wind, 1997

In With the Wind, 1997, overlapping scarves and thread dangle against the gallery wall with opaque and transparent colors fusing, in a sophisticated reflection of traditional painting, even as they are mementos—many of the scarves are from Hodges’ family. Icons of the AIDS epidemic (hung mock flowers, slack sheer scarves, ink drawings on napkins) are part of this work’s interpretive history, and offer a specific path into the work but, if one stays in front of Hodges’ art, a larger world of possible interpretations slowly pushes past first impressions.

All in the Field, 2003

All in the Field, 2003, for instance, with its embroidered flowers and twigs set against a background of dirty green camouflage, seems merely an undoing of macho aggression—the flower stuck in the barrel of the rifle. But, what at first feels trifling unravels to suggest two versions of nature, both equally manufactured and artificial. The camouflage and the flowers share a refined beauty that is crafted, controlled and abstract.

The title All in the Field references the earnest history of field painting, and brings to mind a literal earthen field where flowers rise and fall in some Nietzsche-like eternal recurrence. The camouflage recalls Andy Warhol’s legacy of detachment. Implications of violence and death also arise as delicately stitched flowers and lonely pine cones take on an elegiac notation for the fallen. The battle might also be internal—a kind of psychology of manhood and the way in which a man obscures or openly presents his identity. Hodges unleashes, in a straightforward format, a whole host of potential meanings; he hides depths in something easily digestible and superficially obvious.

In the artist’s many broken glass works, disco balls, Duchamp and seven years bad luck conspire to take simple gestures and make them more than fractured light. There is a wonderful dance of reflected light that slides across the gallery walls and floors as the hours pass from morning to evening. Admittedly, these attractive mirror shards twinkle and dazzle, yet they equivocate between an unabashed beauty and a gauche operatic decoration. They would look equally at home in a restored train station or a posh Miami penthouse. I’m not sneering at Hodges mirrored constructions; I think this odd shifting of the work broadens it. The mosaic puzzle of mirrors reflects our world, but they also break it into distorted, disharmonious bits for us to patch back together.

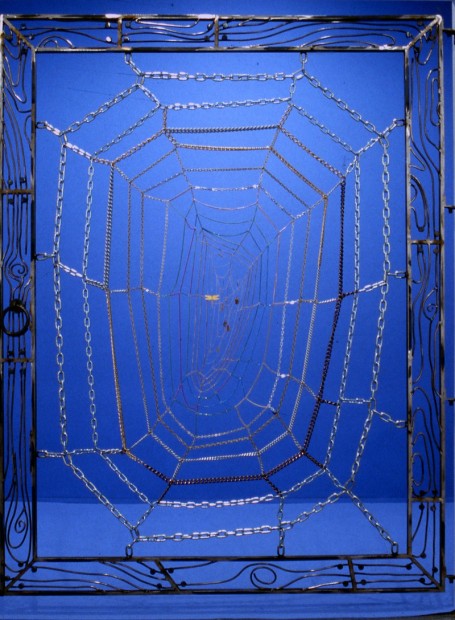

Untitled (Gate), 1991

Hodges regularly strikes a perfect chord when he is at his most unassuming. His white brass-chain spider webs are distilled visual odes. They read as light, delicate webs attached to corners, but as one nears them the chain gives them a weight that is surprising and humorous. Similarly modest, Landscape, 1998, nests a series of button-down shirts within each other like a Russian doll, implying the changing terrain of the body as it ages. Implications of time, memory and death are present in this poignant object.

Untitled (It’s already happened), 2004

In Untitled (It’s already happened), 2004, the artist takes a large-scale photograph of a copse of trees and carefully cuts individual leaves folding them forward and revealing the white of the wall behind the rather dark photo. It is a rudimentary idea that completely transforms the static photo into something animated and alive. The entire surface of the image is activated and made tactile. Hodges makes us look again at an image that we would otherwise only numbly acknowledge. It is a wonderful sleight of hand that Hodges repeats on the reverse side of a different photo in his similarly beguiling Just this (the end), 2010. In this version, Hodges gives us a white-on-white field of cut marks and folded flaps opening to the bare wall. Both these works show Hodges at his most refined, and in some ways, closest to his poetic intentions.

Untitled (one day it all comes true), 2013

His most recent work, Untitled (one day it all comes true), 2013, is a purposefully grand image of fluffy clouds with the light of the sun shining through in radiating lines. One can hardly think of a more mawkish image, as if the hand of God (or Alfred Bierstadt) was about to reach down from above. Hodges subverts this ponderous drama by sewing this wall-sized image of nature as a quilted puzzle of multiple shades of denim. Our most common and ubiquitous clothing material is used to build an image of vast power, giving familiar imagery a second life. Like all of Hodges’ art, this work attempts to address the natural world and refresh the way in which we recognize our place in our environment—however constructed, emotional or burdened by clichés.

Jim Hodges: Give More Than You Take is on view at the Dallas Museum of Art through January 12.