Last night at the Holocaust Museum Houston, Alfredo Jaar delivered an hour and a half lecture about his work. The Chilean-born artist was 17 years old when Pinochet took power in his bloody coup; he spent three weeks in Rwanda during the genocide there in 1994; and recently he made an installation about the tsunami/Fukushima disaster in Japan. In short, he’s seen his fair share of horrors, and he makes somber, likeable art about the horrible things people do to each other. It’s a hot market: of the 10-15 requests for pieces he gets every year, Jaar accepts only one.

During the Q&A afterwards, audience members representing four different nationalities asked questions. A fellow Chilean asked Jaar why he chose ultimately to live in New York? To which he replied, New York is a true amalgamation of the world. He cited the six Korean newspapers and two Greek newspapers that are published there every day.

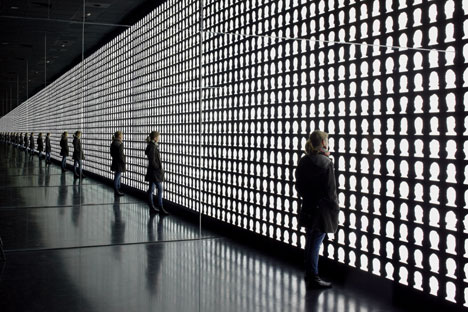

Alfedo Jaar, The Geometry of Conscience, 2010

Then a Norwegian asked for Jaar’s ideas on how to solve the problem of immigration, in the context of the Oslo shootings by a right-wing nutjob in 2011. To paraphrase Jane Lynch’s character in “Wreck it Ralph,” at this point the talk got interesting. For rather than pointing to the melting pot of his adopted city or his own experience as an immigrant, Jaar shrugged his shoulders and said that he didn’t have the answers for the knotty problem of immigration. Fair enough, but then he went on: “This guy [in Norway] was a disturbed individual who had been affected by dangerous ideas. We have to control the dissemination of dangerous ideas.”

Control the dissemination of dangerous ideas? I’d have been less surprised if Jaar had suggested we control the dissemination of dangerous nutjobs (by reinstating homes for the criminally insane, for instance). That said, maybe once you’ve witnessed a real massacre, free speech loses its righteous, First Amendment urgency—although I think there’s a problem with that kind of thinking (or lack thereof) from someone who has chosen to live as an expat in New York City. Jaar also said that preventing another Rwanda-type genocide where the world sits by and does nothing will require an independent panel of intellectuals at the UN who are not beholden to any one country. Which is about as likely as New York suddenly becoming a homogeneous city where only one language is spoken.

Jaar would probably argue that it’s not his job to solve the world’s problems, just focus our attention on them. But it seems the answer to these urgent problems might not lie in yet another elegant, feel-bad-to-feel-good art installation. I’m not saying art is not the answer, or at least an answer. But the answer certainly isn’t fuzzy thinking about restricting free speech and fantasy panels of politburo intellectuals who aren’t beholden to the messy forces of democratic will.

Instead, look at the most cosmopolitan, polyglot cities human beings have congregated in over the millennia, like the one Jaar has made his home. When you let a bunch of people in and let them do pretty much what they want (and say what they want, even when you don’t agree with it), it often seems to work out. Things can run off the rails, and brutal dictators can wrest control, and against that we must be eternally vigilant. But I’m not sure that Jaar’s brand of grand, earnest art that makes us feel bad-good is the path to vigilance. I think it’s just the path to tidy, elegant bows wrapped around horrors that have nothing to do with tidiness or elegance.

Alfredo Jaar, Music (Everything I know I learned the day my son was born), 2013

In Jaar’s defense, not all of his work is gloomy (although the best of it is). Texans wanting to see an example in the flesh need look no further than the Nasher Sculpture Center, which just opened Music (Everything I know I learned the day my son was born), a temporary installation by Jaar as part of the NASHER XCHANGE 10-year anniversary program. A large outdoor room situated in the sculpture garden, with translucent green walls, the space is meant to be refreshing and contemplative. Jaar has worked with three hospitals in fringey Dallas neighborhoods to capture the cries of newborns born during the time of the installation. Those cries are piped into the temporary space at the time of their birth, and every day thereafter at that same time, creating a growing chorus of primordial human sound. The babies themselves will all receive lifetime memberships to the Nasher, which Jaar described as an effort to expand its audience beyond the traditional core of insular art lovers. Overall, the piece is not mind-blowing, and it’s not going to prevent a genocide, but just maybe one of those babies will grow up and actually use their lifetime membership, and be changed for the better because of it.

Rainey Knudson is the founder and publisher of Glasstire.

1 comment

Artists are great at fuzzy thinking. Don’t take that away from us.