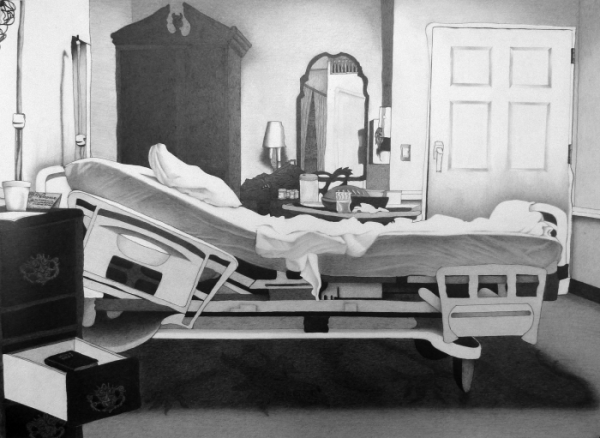

Michael Bise, Empty Room, 2012, graphite on paper, 24 1/2 x 33 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Moody Gallery.

Illness is the night side of life, a more onerous citizenship. Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick. Although we all prefer to use the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place.

– Susan Sontag from Illness as Metaphor

Michael Bise’s most recent autobiographical drawings focus on the artist’s survival of a heart transplant two years ago. Each graphite drawing is like a scaled up panel from a graphic novel showing a different scene from his harrowing experience: an empty hospital bed, the hospital corridor, his unconscious body hooked up to tubes and wires, his doctors, his nurses, and the waiting room. The emotional acuity of each scene and the directness of Bise’s simple process—pencil to paper—give the drawings tremendous presence as momentary windows into the “kingdom of the sick,” Susan Sontag’s phrase from which the exhibition borrows its title.

Michael Bise, Stained Wall, 2013, graphite on paper, 49 1/2 x 59 1/4 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Moody Gallery.

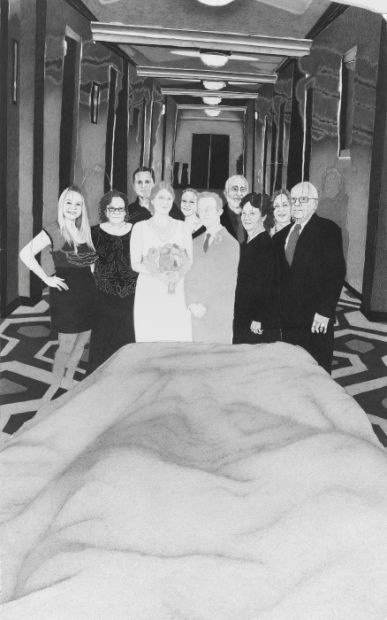

With Bise’s drawings, living in the soft overlays of graphite that make up a crumpled pillow or bed sheet or the opaque marks of pitch-black shadows is an emotional resonance. Yet this resonance owes as much to Bise’s meticulous technique as it does to how thoughtfully he frames and constructs the scenes. In each drawing, a specific kind of space within it gives a different psychological charge. In Empty Room, a smaller drawing at 24 ½” x 33” compared to the larger works, an intimate view of an empty hospital bed with domestic furniture surrounding it is shown in a straightforward yet poignant way. Is this the moment after someone has passed and only their body’s imprint remains? The askew angle of a nightstand with a drawer open to expose a bible and a disorienting reflection in the room’s mirror of a shadowy figure provide clues that there is more to this placid scene. In contrast, more liberty is taken with spatial distortion in the largest drawing in the exhibition. At over six feet high by four feet wide, Elevator at the End of the Hall is human scaled to put the viewer in Bise’s vantage point as he presumably rolls down a foreboding, off-kilter hallway to be taken to surgery. Fluorescent lights leave hallucinatory vibrations on the walls and at the foot of the bed is a transposed familial portrait that appears to be taken from the artist’s wedding. Eerily rendered, “real” figures are mixed with ghost-like outlines of deceased family members and a pale white bride and groom.

Michael Bise, Elevator at the End of the Hall, 2013, graphite on paper, 81 x 50 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Moody Gallery.

This powerful image, “Elevator at the End of Hall,” is the keystone of the exhibition where many of the threads running throughout Bise’s experience are expressed in one drawing. Bise gave a candid and moving artist talk seated next to this drawing as he explained how the heart transplant had changed his life as a person and in turn, an artist. A self-reliant atheist, Bise believed that no matter what he could be fine alone, and he firmly rejected his Pentecostal family’s belief in anything beyond the concrete facts of existence. These two beliefs were momentarily shaken by hallucinations Bise experienced as a result of anesthesia, and more importantly, a 60% loss in vision he suffered four months after his transplant. The heart surgery did not kill him, but the loss in vision left him suicidal and uncertain whether he could continue as an artist as he feared the possibility of complete blindness. His normal means of philosophically and psychologically coping with such trauma failed him, and he leaned on his family as he accepted the form of love they could give him regardless of its spiritual inflection. He still did not agree with their religious views, and he did not expect a miracle healing or supernatural occurrence, yet he accepted their prayers over the phone as an essential form of support to relieve his psychological pain. His gallerist Betty Moody also saved him by giving him the deadline of six months to make a new show. Working again became an act of survival as Bise was forced back into the studio and had to figure out how to draw again despite his vision loss.

Michael Bise, Sleeping Man, 2012, graphite on paper, 14 1/2 x 19 1/4 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Moody Gallery.

Of course he needed much more than six months, but he slowly allowed something outside of concrete experience to make its way into these drawings. Previously his rule was that everything had to have a link to the physical world and that scenes or scenarios could not be invented if they did not actually occur, a kind of autobiographical rigor of sorts. Bise began breaking his own rules and, instead of documenting actual occurrences, he began depicting psychological conditions. For example, in the drawing Sleeping Man, Bise is ensnared in the tentacles of tubes and wires plugged into his head. The hospital bed improbably floats above a black abyss of a background rather than grounded in an actual space. The image has a sci-fi feel of a dystopia where it is unclear whether the helpless character is being kept alive or having the life siphoned from him. The suspended bed is a metaphor for a kind of purgatory between life and death. One of the exhibition’s most powerful drawings, The Waiting Room shows a different kind of limbo where not the patient, but the patient’s loved one (Bise’s wife) has to sit with the uncertainty of whether her husband will survive. To show the precarious state, Bise tilts a menacing display case of animal figurines, so that it looks as if it might topple over onto her. Also, alluding to the artist’s own gaps of vision are inexplicable circles of distortion (imagine viewing this scene through a window with water droplets that bend, twist, and ripple the lines.)

Michael Bise, Waiting Room, 2013, graphite on paper, 37 1/4 x 50 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Moody Gallery.

A drawing like The Waiting Room is so complex and evocative because of these new possibilities that Bise has allowed himself as an artist. Hearing Bise tell his story at his artist talk made me think about Norman E. Rosenthal, a professor of psychiatry, who recently released a book called The Gift of Adversity. Intrigued by people who experience terrible things and later describe them as being “for the best,” Rosenthal explores through stories, including his own of being nearly stabbed to death, adversity’s ability to help an individual achieve a new understanding of the world. Rosenthal’s perspective made me think of how Bise’s adversity has produced a suite of drawings that offer us an alternative and unblinking view of the experience of death, illness, and our medical system. Our culture largely denies death, aging, and illness, and it is not surprising that Sontag conceptualizes illness as a separate world, full of different citizens. Bise’s drawings show a citizen willing to tell the story of crossing between these worlds. I imagine that Bise is just beginning to reflect on his experience and will revisit this story many times. Luckily for us, he is brave and skillful enough to share it.

Michael Bise’s Love in the Kingdom of the Sick is on view at Houston’s Moody Gallery through October 12.

Michael Bise: Life and Death is also on view at the Galveston Arts Center until September 29.

2 comments

Thanks very much for your thoughtful review Josh.

Thank you Michael for making this courageous and visceral work!