Passengers

Mariano Dal Verme’s current exhibition at Sicardi gallery investigates the limits of drawing, playing with and often bypassing any colloquial definition of the form. Combining drawings in the traditional representational, mark-on-paper technique with sculptural works that surpass the limitations of the two-dimensional medium, Dal Verme combines graphite and paper in impossibly intricate works that seem to both defy and encompass the very essence of marking on paper.

Before one even enters the main room, Passengers, hung on the outside wall of the gallery space, presents drawings in a strikingly new way. An antique bus ticket dispenser is mounted on the wall, a tarnished silver object with jagged edges. Instead of printed tickets run through the machinery, there are rolls of paper with ink drawings of people’s faces on them. About an inch tall and slightly cartoonish, these drawings wouldn’t be remarkable on their own; what I liked best was seeing a standardized, machine-printed ticket replaced by hundreds of original, hand-drawn faces. Visitors are encouraged to rip a face off of the dispenser as if it were a ticket, giving the work a transient quality and making it less about the particular drawings you see, and more about the act of removing them. The machine pushes new drawings forward as if it is producing them, separating the casually drawn representational figures from the artist and making the source of the image ambiguous.

Stepping into the main gallery is almost like stepping into a completely different artist’s show. Apart from The Book of Love, a notebook that features more traditional ink drawings of couples’ faces, the rest of the works are abstract and, up close, completely abandon any semblance of two-dimensional drawing.

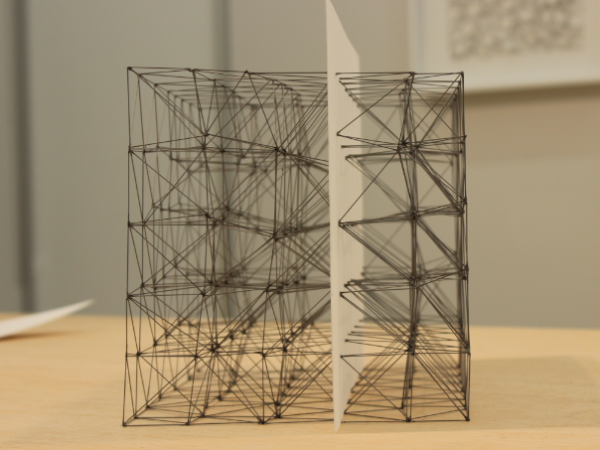

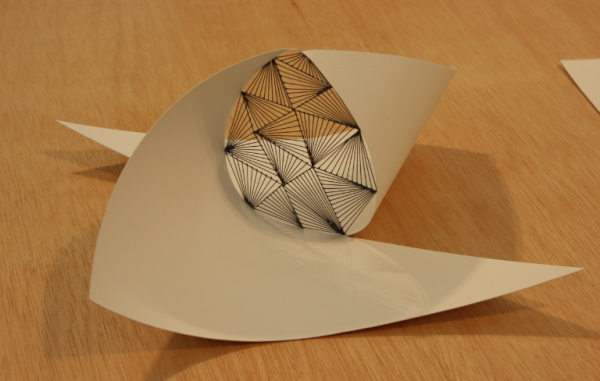

Most works are constructions of graphite sticks and paper — sometimes even graphite on paper — but built up in an architectural way or laid flat to create texture. Many of these works can stand unaided on a wooden table or shelf, incorporating sculptural elements with Dal Verme’s deconstructive concept of drawing. In Untitled (2013) towers of millimeter-wide graphite sticks are glued together into detailed geometric forms, working as a scaffolding to sandwich a square of watercolor paper. In another untitled work, triangular rays are suspended in the circular center of a loop of paper, evoking what could be the world’s most delicate roller coaster.

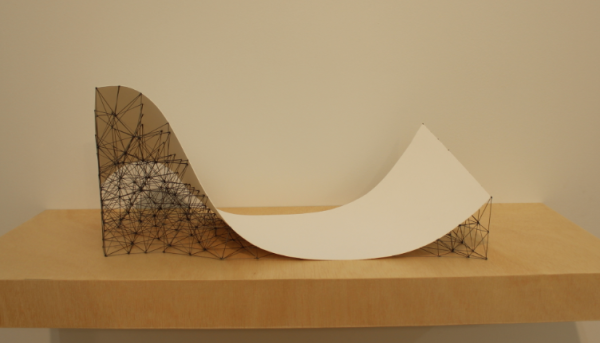

In yet another Untitled (2013) work located in the back of the room, a strangely spidery lattice of graphite supports a heavy drape of paper, beautifully juxtaposing the creamy paper’s smooth undulation with the graphite’s awkward angularity. The position of each material is reversed: the graphite, so brittle and flimsy (in stick form), bears the mass of thick paper, rather than being applied to it.

In yet another Untitled (2013) work located in the back of the room, a strangely spidery lattice of graphite supports a heavy drape of paper, beautifully juxtaposing the creamy paper’s smooth undulation with the graphite’s awkward angularity. The position of each material is reversed: the graphite, so brittle and flimsy (in stick form), bears the mass of thick paper, rather than being applied to it.

There is something whimsical and decidedly imaginative about these works, despite their clearly calculated geometry. The combination of the delicate materials with industrial, angular forms is compelling, as well as their scale. It’s difficult not to think of these works as architectural models for impossible buildings or über-modern dollhouses; the miniature scale and striking detail of each work feels consciously playful.

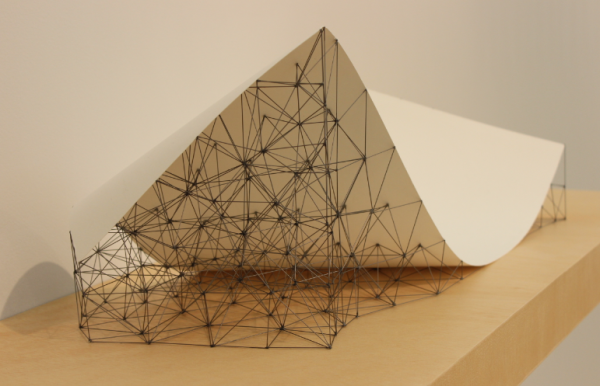

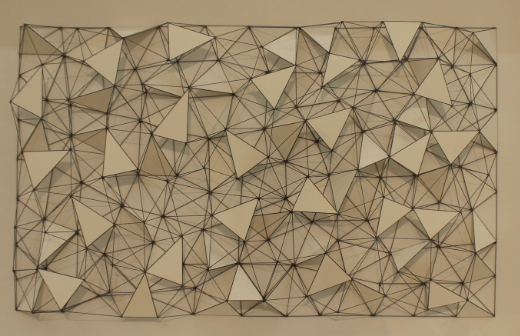

In one of my favorite pieces, the graphite forms a complex web of interlocking triangles, some empty and some filled with perfectly fitted wedges of paper. This work in particular plays with issues of dimensionality and space, with the graphite emerging from a paper base and smaller cuts of paper assimilated into the angular network of graphite sticks. From far away, the viewer’s eye can barely register the piece’s depth, but as you approach the work, you can tell that line and paper are discrete objects that work together to create an image, instead of relying on one another. The piece rethinks the interaction between paper and graphite, how the two can build off of one another, instead of one being on top of, or smudged into, or dragged across the other. The hierarchy of drawing breaks down in this meticulously constructed piece.

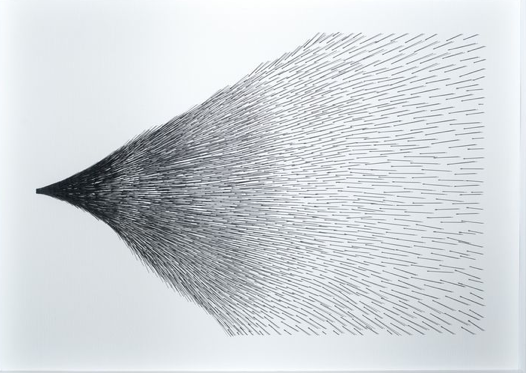

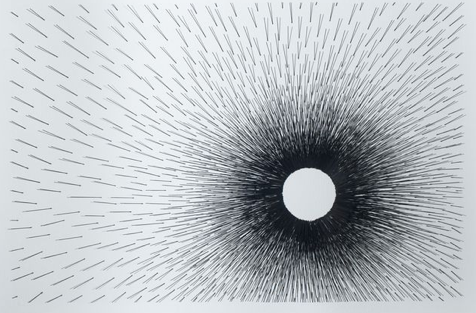

Two framed pieces are flatter, while still addressing issues of drawing. In these works, hundreds of graphite sticks sweep out from a locus, or out from a circle, respectively. Moving from a compact to a more expansive arrangement, the graphite’s overall effect is similar to shading or smudging a pencil. Looking closely, the sticks resemble a porcupine’s quills, or a close-up of rigid hair. Again, Dal Verme seems to be playing with our conceptions of what drawing is and should be, referencing the conventions of drawing using a bizarre textural quirk.

In this show, Dal Verme contrasts the restrictions and the possibilities of drawing as it has been defined by history. By including works that both uphold and flout these limitations, Dal Verme deconstructs the medium and forces you to acknowledge the fragility of paper and pencil while considering the possibility of a more monumental way to combine them. Fragility seems like a key word for the show; perhaps the term “drawing” is fragile, easily shattered by enterprising artists. His work has a rare liveliness that isn’t necessarily bound to his theory, the show ends up feeling less like a rebellion and more like an experiment, an opportunity for Dal Verme to humor his imagination and showcase a true reinterpretation of the craft.

Mariano Dal Verme: On Drawing will be on view at Sicardi Gallery in Houston through August 31.