Sitting idle during summer vacation isn’t so bad, especially when Michigan heat is worse than in Texas. And, in a house without AC, the best bet is sitting with feet propped up and fan gently whirring overhead, while reading actual, printed, non-heat-emitting books.

It used to be that almost all the books I read were about art history and art theory. But I’ve broadened a bit, in an attempt to find writing that was relevant but less turgid. Success has been mixed. Here’s a recent trio of titles:

Dutch: Biography of a Language by Roland Willemyns. 2013. Published by Oxford University Press.

Dutch: Biography of a Language by Roland Willemyns. 2013. Published by Oxford University Press.

Why the hell a history of Dutch? Because I want to learn to speak, read and write a language that continues to be important in the place (West Michigan) I live. And my research focuses on Netherlandish painting (15th- through 21st-century). And I thought it might be easy to learn.

Anyway, reading about the cultural history of any language makes it easier to understand why it’s the way it is. Dutch proves this out, even though most of its linguistic references make my brain want to explode. It’s given me greater insight into particular artists and their works—from van der Weyden to Delvoye—that never cease to challenge me. Will it help me to learn the language? It might, if I don’t panic about the “lexical, phonological and morpho-syntactic dynamics in the transitional zone between the colloquial speech and the standard language.” (p 251)

Why Things are Falling Apart: and What We Can Do About It by Charles Hugh Smith. 2013 (revised edition). Published by Oftwominds.com.

Why Things are Falling Apart is a book I bought, then put off reading because, not having done my homework about the author, I feared it was written by some Tea Party wingnut. Actually, Smith seems to fall somewhere between the Tea Party and the Occupy Movement. He’s not a moderate on the conventional political continuum, but an outsider who sees the validity of many points of view.

Smith is particularly unhappy with government’s complicity with immense banks. One point that he repeats frequently is that the Federal Reserve, which Ben Bernanke chairs, is a private bank that is funded by several private banks. I’m with him on this point of concern (if not outrage). But I’m disappointed with his seeming indifference to what will happen to millions of Americans who’ve lost agency—not to mention millions of savvy, generally self-reliant people who still need help with things like medical expenses. Much of what we expect from government is based on interpretation. Smith says the Feds need to maintain “the means to distribute sufficient food and energy to the entire population” (p 103) and protect “the nation’s commons [air, water, soil] from despoliation”. But what does this mean in real terms of funding the FDA or the EPA?

Found Sculpture and Photography from Surrealism to Contemporary Art, edited by Anna Dezeuze and Julia Kelly. 2013. Published by Ashgate.

Then there’s Found Sculpture and Photography, an academic anthology on several topics I love, ranging from the everyday object to anything found to surrealism. Most of the essays are a joy to read: they thoroughly unpack their talking points without grinding issues into fine dust. My favorites are Carrie Lambert-Beatty’s writing about Terry Fox’s Children’s Tapes; and Anna Dezeuze’s essay on Richard Wentworth’s photographs of quotidian objects in banal situations (the proverbial broom propped in a corner, for example).

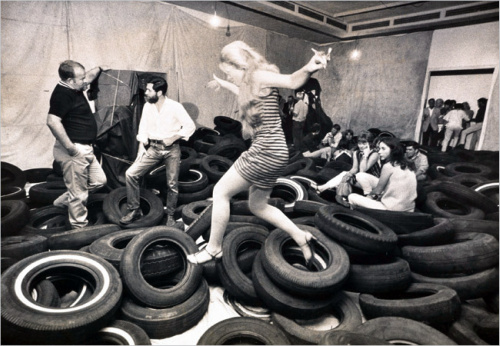

But, where the above writers address subjects in ways that are enjoyable in themselves—and entice me to experience both bodies of work first-hand—Martha Buskirk’s essay on Allan Kaprow illustrates much that is wrong with humanities writing. For example:

“Taking a different tack, the staged photographs used as illustration for his

1975 publication Air Condition, which evoke the intervening conceptual en-

gagement with the snapshot, function as instructions rather than records in

the context of increasingly low-key and often private activities that, once

realised, are known through the fragmentary verbal accounts or ‘gossip’ that

Kaprow turned to in the place of the false transparency of other forms of docu-

mentation.” (p 81)

I won’t even go into the British-born penchant for sub-clauses here. The larger problem is mistaking arid verbosity for the credibility of objective, thoroughly rehearsed information. Writing about art history, literature and other humanities subjects is not the same as writing about science and mathematics. It’s possible to be credible without dessicated dissection. Instead of making those who control the purse take humanities more seriously, this kind of approach only persuades them that humanists are out of touch. People, this is not the kind of message we need to be sending!