Lifelike, the summer exhibition at the Blanton Museum of Art, probes reality and its attendant subjective interpretations, making ordinary things seem otherworldly and special. The work in the show, spanning from the late 1960s to the present, creates moment after moment of “aha.” As in “Oh, wow, you mean that trash bag is made of marble?” In fact the trash bag, Jud Nelson’s Hefty 2-Ply (1979-1981), was carved out of Carrara marble, the same material Michelangelo and Bernini used to create their masterpieces. The artist uses a historically significant material to make a very close resemblance to a bag of trash. This sleight of hand occurs throughout the exhibition, making the viewer second guess his or her preconceived notions about what is and isn’t real.

The exhibition originated at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and contains a significant number of works from their permanent collection. The unstable nature of reality is a straightforward enough concept, which makes Lifelike the perfect summer museum show. Breezy and uncomplicated, nary a whiff of the political (save for a tiny and easily overlooked Ai Wei Wei jar of sunflower seeds), the show displays strong artistic skill (“how did they do that?”) and a lot of fun trickery of the eye. Take for instance, Maurizio Cattelan’s Untitled (2001), a set of miniature elevator doors that open and close, blink and light up just like real elevators only tiny. Or Thomas Demand’s video Rain/Regen (2008), a stop-motion animation that looks like rain hitting a surface. Read the label and you’ll find that the droplets of “rain” are actually candy wrappers that have been photographed through panes of glass. The soft pitter patter (a glorious sound to any Texans’ ears), is not the actual sound of rain at all, but instead, is the crackle and pop of eggs frying. The next day I made a fried egg and listened closely, “Huh, it does sound like rain.” And really this is when the exhibition is most effective—that it might push the viewer to re-examine the overlooked items of our everyday life.

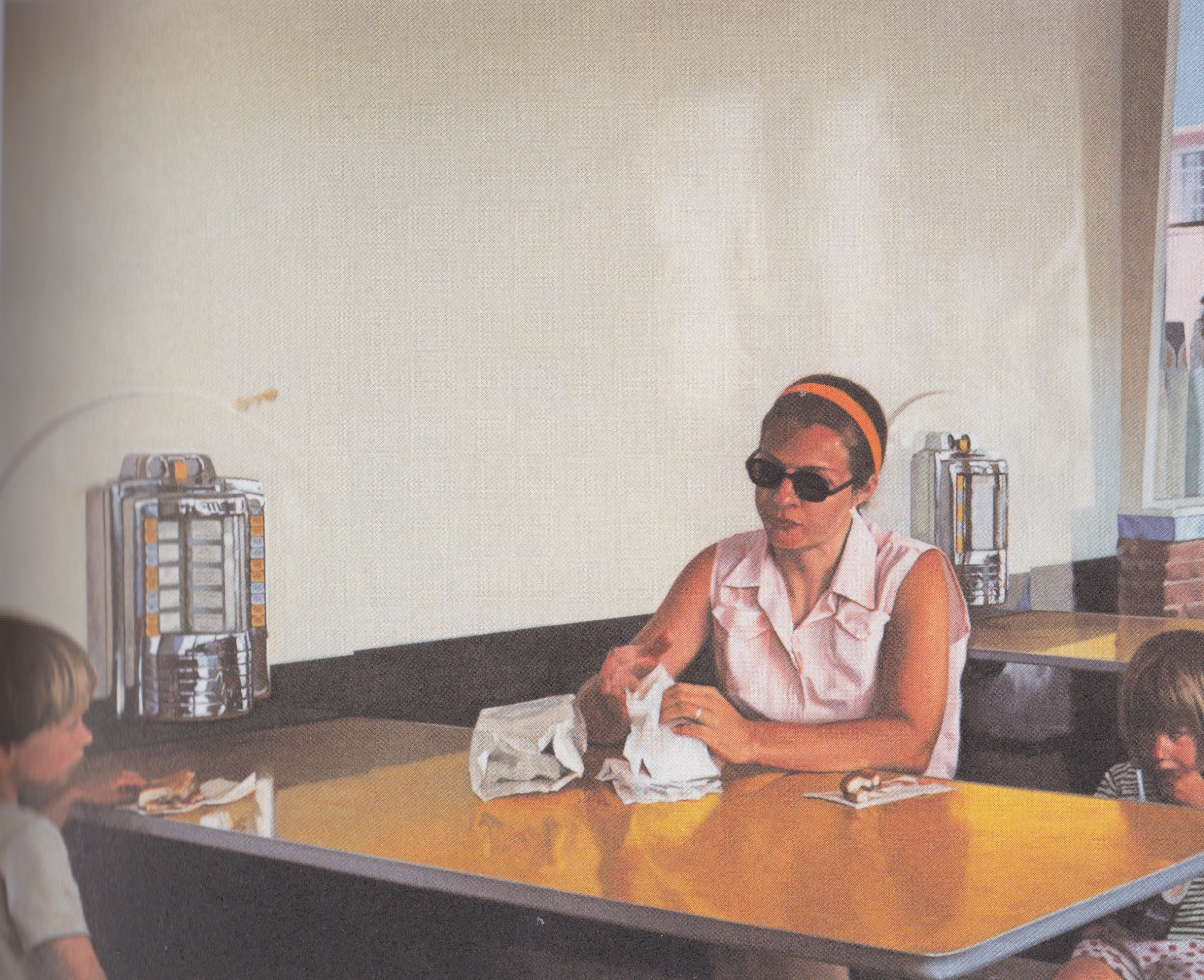

The artists in the exhibition take the ordinary and seek to make it other through skillful manipulation of materials. The show is most successful in its concentration on the return of realism in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Turning away from the emotionalism and heroism of Abstract Expressionism, these artists brought back figuration through the form of the photograph. The elision of photography and painting as displayed in works by Chuck Close, Robert Bechtle, Sylvia Mangold and Gerhard Richter give the show a necessary historical throughline. The New Realists, as art historian Linda Nochlin calls this group of artists in her 1968 essay Realism Now, allowed a return to figurative representation without having to maintain the history of the avant-garde in painting. New Realism remained cool and banal like the Pop artists, yet, unlike Pop, it looked to the photographs of our everyday lives and not the commercial world. The divide between pop and the New Realists is evident when looking at a work in the Blanton show by Robert Bechtle. His painting Fosters Freeze does not celebrate the form of the ice cream cone, but rather, is a photo-realist rendering of his wife and children idly eating at a diner; an incidental passing moment worthy of Manet.

Nochlin relates the banality inherent to the New Realists to the nineteenth-century realists such as Manet: “And, as in the case with the nineteenth century realists, one feels with their twentieth century counterparts that the ordinariness of the artistic statement, or even its ugliness, is precisely the result of trying to get at how things actually are in a specific time and place, rather than how they might be or should be.”[1] To “get at how things actually are” meant describing the basic things in our world, which include cars, store windows, marquee signs, and hardwood floors. All of these things are rendered through the flattening of the photographic lens. The New Realists played with the banality inherent to the ubiquity and disposability of the photographic image in their reinvention of representational painting.

The ordinary extends to sculptures as made clear through the inclusion of several everyday objects in the gallery such as Vija Celmins’ fabulous oversized pink eraser, slightly worn down at the edges. Or Alex Hay’s 1968 larger-than-life Paper Bag, brown and crinkled from use. In the essay “The Ersatz Object,” Kim Levin discusses the return to realism or nature in the guise of the ordinary object. She suggests that by 1969, while most artists were preoccupied with physical presence existing through raw materials or, simply, ideas, form was covertly returning to nature. She states: “And although this may well have meant the disintegration of modern art, art at the same time was reemerging from the ashes in the protective guise of life.”[2] Nature, the real, is being created in such a way that the artifice of mimesis becomes an integral part of the artistic experience.

Kaz Oshiro, “Zero Case Spinner (Gun Metal-torn FRAGILE stickers), 2011, acrylic, Bondo on stretched canvas, caster wheels

The big reveal, fakery, is what compels some of the best work in Lifelike. From the front side, Kaz Oshiro’s sculpture Zero Case Spinner (Gun Metal-torn FRAGILE stickers) (2011) looks like a beat up suitcase. Go around the sculpture and the backside reveals the support and the canvas. Oshiro highlights and makes clear that, despite the initial appearance, the work is very much a painting. Current trends in realism, as well as the New Realists of the 1960s and 70s, undercut traditional modes of representation by referring to its artifice. These artists constantly destabilize any notion of the referent or origin by reveling in the fake. Levin explains: “It conceals its own reality by mocking another, arousing dread, confusion, and the shock of recognition. . .The degree of its lifelikeness corresponds perversely to the awareness of its deceit.”[3] The artists in Lifelike successfully take from the natural world and make of it, largely, an unnatural rendering. In the process of examining these works of art, the viewer experiences the ordinary as something else, as something, perhaps, even extraordinary.