Pat O’Neill, Horizontal Boundaries

Large-Scale: Experimental Films on 35mm at Austin’s Alamo Drafthouse Ritz theater featured classic and contemporary cinema. No film acted as a window on the world; each film claimed itself—its space—as a way to engage the state of being alive, a way of living in the world. Productions ranged from 1960 through 2011—that’s 51 years of film art—with the older films rivaling the recent in their impact.

Screenings of artists’ noncommercial cinema in digital form are rare enough. Showings of experimental film on 35mm are veritably unheard of. Not many artists have produced work on this more expensive format in the first place (as compared to 16mm and video) and the logistics of presenting 35mm shorts is daunting. For those in attendance at the Alamo Drafthouse Ritz on June 1, a sunny Saturday afternoon in Austin, Large-Scale was an experience like no other.

Although all the titles were indeed 35mm, they nonetheless had a multitude of aspect ratios: some boxier, some wider. When the shape of the image changed from one title to the next, the projectionist adjusted the red velvet curtains on either side of the screen—moving them closer together for some films and distancing them for others. The movement and the variance of the curtains provided an unexpected layer and rhythm, creating the effect of a show within a show and enhancing the already performative and theatrical nature of the event.

Five of the eleven films were silent. Another unanticipated factor in the experience of the program was the shift back and forth between highly intentional sound coming through speakers and the ambient tones of the theater and audience. While the soundtrack of Jordan’s Our Lady of the Sphere (1969) played an integral role in elucidating the film’s humor, silence enabled the fullest appreciation of optical rhythm in The Dante Quartet (1987) by Stan Brakhage.

Stan Brakhage, The Dante Quartet

The quality of the prints and projection was remarkable, far removed from a distorted image on a computer screen or a phone. With the larger format, there was more definition to the image and a greater intensity of color. This “chroma-hyperabundance” only made the already psychedelic feel of the artists’ own hands on the celluloid all the more transfixing. From Brakhage’s trademark hand-painting through Louise Bourque’s submitting her images to “incubation in menstrual blood for several months” in Jours en Fleurs (2003) to Kerry Laitala’s use of D.I.Y. collage techniques in Conjuror’s Box (2011) including Cinegramming, hand-painting, and the re-animation of magic lantern slides.

Christine Battle, Three Hours Fifteen Minutes Before the Hurricane

Joseph Cornell’s assemblages inspired Christina Battle’s Three Hours, Fifteen Minutes Before the Hurricane (2006), which also referenced early cinema through intertitles of Katrina survivors’ words such as “the lights began to flicker.”

Traveling through family history and merging his story with his grandmother’s brought Jane’s Window (2005) by Chris Kennedy to fruition. The interface between still and moving images, and the technology used to make them, provided the conceptual laboratory out of which Tomonari Nishikawa’s 16-18-4 (2008) emerged. Pat O’Neill was also obsessed with disturbing and displacing any notions of the film frame as representational in his odyssey Horizontal Boundaries (2008).

Peter Tscherkassky, Dream Work (for Man Ray)

The three Austrians on the bill made some of the program’s most commanding films. In his science and art film Realtime (2002), Siegfried Fruhauf sculpted a space of wonder around that most fundamental key to human existence: the sun. Peter Tscherkassky based the handmade approach of Dream Work (for Man Ray) (2001) on Ray’s rayographs of 1923, transferring and compositing found footage onto “unexposed film stock” through a laborious frame-by-frame method. The dream space at once constructed and explored by the work’s cyclone of imagery ignited a desire for a continual return and an incessant grasping at meaning.

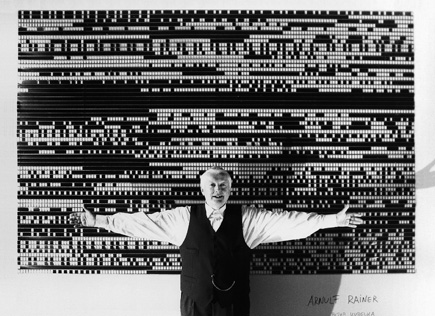

Peter Kubelka, Arnulf Rainier

Peter Kubelka’s Arnulf Rainer (1960), an image-less artwork of white frames intercut with black, called emphatically for a cinema of immediacy. More than the other titles in the program, it directly pointed out the way that these hand-manipulated, large-scale films act as a pilgrimage towards real, lived experience, which seems to be ever-receding. Language’s inadequacy to convey the play of the curtains in the overall sensation of the program is but a prelude to the impossibility of knowing this film by Kubelka (that in theory barely exists) without encountering its living form. What Brakhage said of his friend’s oeuvre, “These films must […] be very truly seen and heard to be believed!” sums up Large-Scale.

Large-Scale: Experimental Films on 35mm was curated by Ekrem Serdar of Experimental Response Cinema, and presented on June 1, 2013 at the Alamo Drafthouse Ritz theater in Austin.