Thanks to Rice University’s Chao Center for Asian Studies, who Rice Gallery is working with for an upcoming conference in Spring 2014, I was able to travel to China for about two weeks in early June. My trip began in Hong Kong for Art Basel and the rest of my time was spent in Beijing.

Jet lagged and stepping into Art Basel was weirdly dislocating. I was in Asia for the first time, yet walking around the white-walled booths felt like I could’ve been back in Houston at the George R. Brown Convention Center at the Texas Contemporary, granted surrounded by different art.

Like other art fairs I have been to, there was good work, bad work, and plenty of attention-seekers in the overwhelming stew: shiny work, colorful work, optical illusion work that changed when you walked by it, work made of a million little parts, work made of something unexpected, and work not-so-ironically about money.

A definite attention-getter and crowd-pleaser: Damien Hirst’s patterned painting made from insect specimens on canvas. I wikipedia’ed the title, and it refers to the “river of wailing” in the underworld from Greek mythology. The work seemed more embellished and decorative than mournful and hellish, but maybe that’s the point.

Loved the placement and strangeness of this parody of Rodin by Japanese artist Makoto Aida. Aida says, “‘Ongiri Kamen’ is my alter ego character … he embodies my personal qualities: lazy, optimistic, unrefined, lethargic, idle.”

Houston, does this look familiar? I had no idea you could also purchase Jaume Plensa’s Buffalo Bayou sculptures room-sized.

This video was made entirely from images from Google Street View and paired with audio found from YouTube. It was kind of amazing to take a scenic trip through Hong Kong via the stitched together images. The audio felt like random voiceover and was more difficult to place or understand its relationship to the imagery.

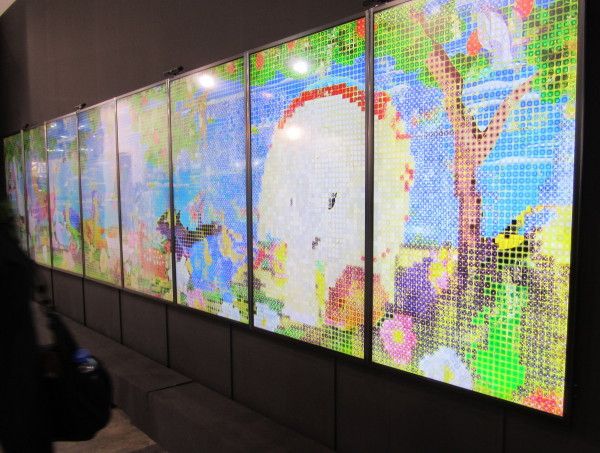

This was a fantastical landscape full of stylized, anime-like animals. When you walked by sensors on top of the screen, your body’s shadow showed up as changing pixels in the display. Despite wishing I could go to that strange little world, the interactive element did not seem completely necessary or convincingly take you there. These guys below still tried though …

The image below shows a totally different kind of art and “interactivity.” Giant sword in your way at an art fair? Step over it.

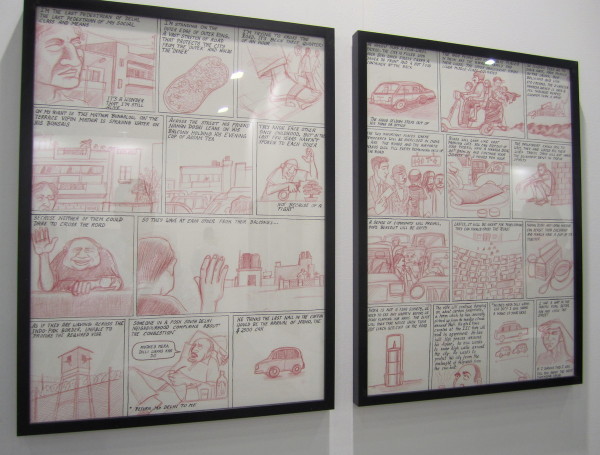

I liked this cartoon strip from graphic novelist Sarnath Banerjee about traffic, cars, and life in India. In the Project 88 gallery booth, I flipped through his newest book The Harappa Files, and I liked some of the illustrations and would like to read it.

Also at the Mumbai Project 88 gallery booth, Pakistani artist Risham Syed’s small, 4×6 inch acrylic paintings show new homes in Pakistan. The houses go up very quickly and the backside is often left unfinished. I loved the scale of this work and the seemingly simple, straightforward views documenting economic change in Pakistan.

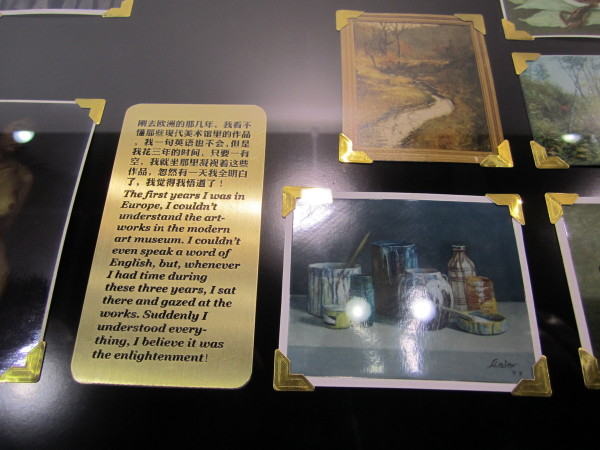

A nice video installation by Li Ran reconciling his own father’s work as an artist. The work pairs a campy, silent video with his father’s actual work and a glass case full of postcard-sized reproductions of works of art and cryptic texts. Ran’s work deals with how Chinese artists have been influenced by Western, modern art.

Unfortunately I cannot find in my notes the name of this artist or gallery, but it was a comment on the Mao Zedong mausoleum where you can view Mao’s preserved body. This was just the first of other examples on my trip of artists playing with Mao’s likeness.

Speaking of creepy things that are inanimate but feel alive, Marnie Weber’s “Log Lady & Dirty Bunny” had shades of Paul McCarthy’s Disney-as-nightmare theme. The pose, size, and eyes of this dirty bunny really made it feel like it was going to turn into a performance piece at any second and jump off the log.

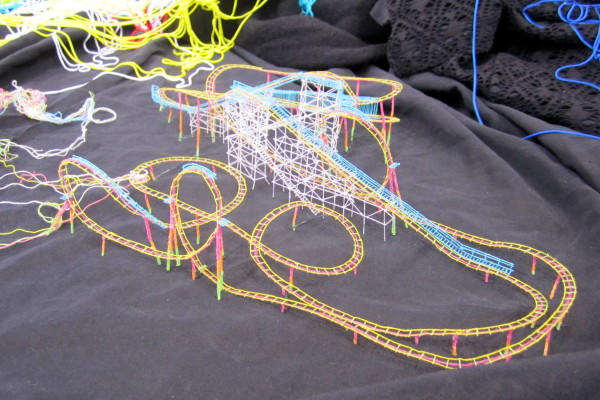

People were clamoring to take pictures of Iwasaki’s intricate cityscape that grew out of common objects: towels, piles of string, sponges, brushes, books, etc. The pieces are incredibly well made, but sort of left me wondering what the idea might be beyond the initial surprise and wonderment.

Finally, you can never escape an art fair without some good people watching. Which one’s art? This person with a soccer ball backpack, boots, and fishnets had a stare down with an equally ornate sculpture.

Now, off to Beijing …

When I arrived in Beijing, I was not sure how I was going to survive for nine days in what felt like an austere, bleak/gray, polluted city with chunky monoliths of glass buildings. Traffic and language barrier aside, it seemed dense beyond belief and impenetrable. Luckily, each day I loved the city a little bit more, but I still feel like I barely scratched the surface.

The first stop was the famous 798 art district. It was kind of like a mix of Chelsea/Soho. The galleries and museums were large spaces converted from old military factories, but parts still felt in a state of disrepair with crumbling sidewalks and dirty alleyways. There were touristy aspects to it with kitschy galleries, souvenir shops, clothing stores, and cafes. I saw several fashion and wedding shoots going on where obviously the art district was being used as a contrasting, “edgy” backdrop.

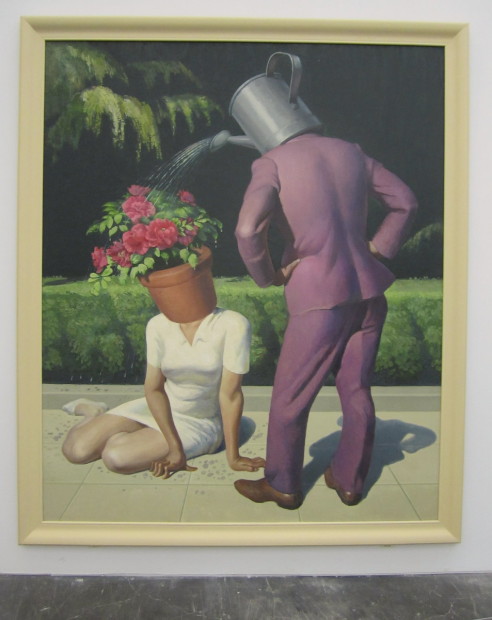

One of the primary museum spaces for contemporary art is the Ullens Center. Filling the massive main exhibition space was a retrospective of paintings by Wang Xingwei. Wang paints in a huge range of styles and subject matter. Some felt opaque and puzzling, as if I couldn’t decode the visual riddle, and others were absurd and funny.

One provocative quote of Xingwei’s: “I am a painter, and I don’t think that painter and artist are exactly the same thing.” I do not know the context of this quote, but I am guessing that it could allude to the job and craft of painting under the communist government. As commissioned propaganda images, painting’s appropriate subject matter and function is clearly defined and controlled. Looking at Xingwei’s work, I thought of Neo Rauch and a kind of surreal assimilation of social realist painting mixed with modern/contemporary influences. Xingwei’s work is very different from Rauch’s and focuses more on portraiture, where often a solitary figure or couple will be depicted in a bizarre landscape or scenario.

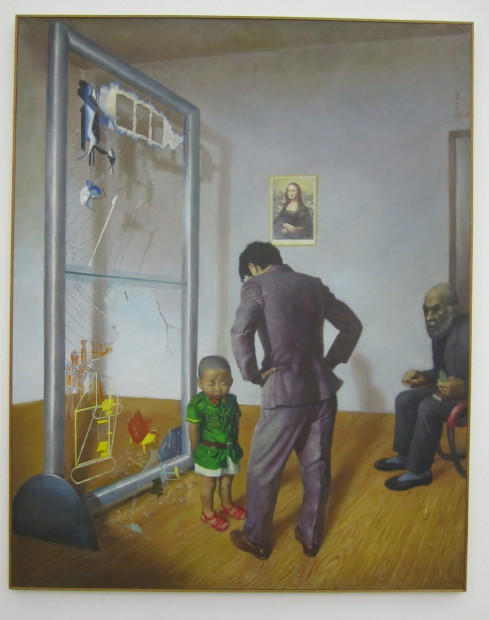

In the above painting, a young child in a military uniform appears to be scolded for breaking Duchamp’s “Large Glass.” Paintings like this and much of the art in China is in a dialogue between East/West and the absorption of modern art history. This dialogue and anxiety over influence is nothing new, but still a point of concern for some Chinese artists we met with as they try to integrate what they think of as Chinese aesthetics with contemporary art. Often, while looking at paintings like Wang Xingwei’s, it was difficult to know what cultural references I was missing as an outsider not as closely engaged with such issues.

Another thread that ran throughout much of the art: Duchamp! He seemed to be everywhere. Near Wang Xingwei’s exhibition was another gallery in the museum devoted to Chinese artists making pieces that owed something to Duchamp. The exhibition contained the first works by Duchamp to be shown in China, including museum posters, notes, sketches, and Duchamp’s mini-museums/collections of his works in boxes and valises. Other works I saw referenced Duchamp, and an artist I met with cited him as an important influence in thinking how art and everyday life can merge.

Now, onto more in the 798 district …

Above is an installation at Long March Space, one of the larger commercial galleries. Xu Zhen and his collective “MadeInCompany” filled the gallery with (literally) tons of sod and plants. The rocky paths mirrored different protest routes from across the world and were broken up with photo cutouts like roadside attractions.

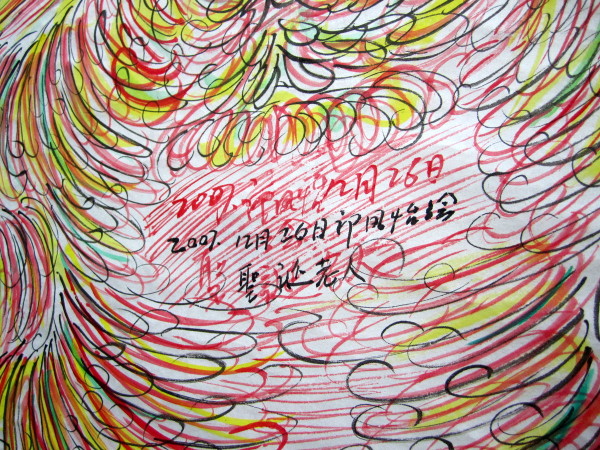

In the backspace of Long March, were drawings by visionary, self-trained artist Guo Fengyi. Using colored ink on rice paper, Guo expresses ancient/folk Chinese ideas about energy and the body in obsessive, curlicue lines. In each of these drawings the mystic figure is mirrored and takes on a totemic presence. If my memory is correct, the figure with the red cap is actually based on Santa Claus. It didn’t surprise me to learn that Guo Fengyi’s obsessive, repetitive work is also included in curator Massimiliano Gioni’s “The Encyclopedic Palace” at the Venice Biennale, an exhibition including many artists devoted obsession, repetition, and accumulation.

Now to the next arts district, Caochangdi …

Newer and more pristine than the 798 is the Caochangdi district on the outskirts of Beijing. Because it is remote and difficult to find, we had to hire a driver for the day who knew the area. Ai Weiwei was the catalyst for the creation of the Caochangdi district when he moved his studio there in early 2000.

He designed a red brick complex of buildings that house galleries and artist studios. The buildings are set on irregular angles that create a maze-like space of narrow alleys that open into plazas. The design seemed to synthesize the austerity of the forbidden city with the density and claustrophobia of the “hutongs” (crowded alleyways tucked away in the cracks of the city in Beijing where people live and many small vendors sell things).

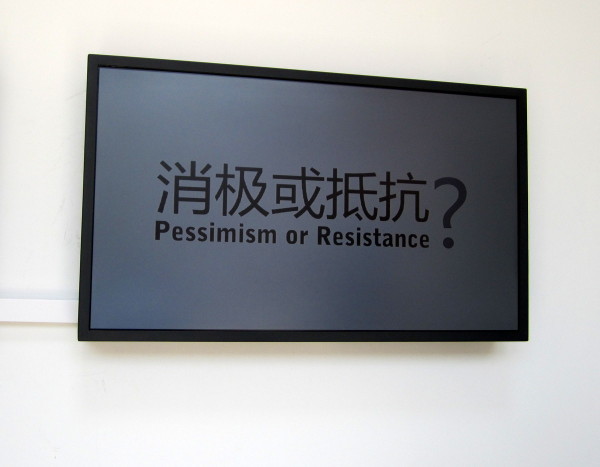

One of my favorite exhibitions was a group show of more political work at Taikang Space. The exhibition was slightly different from the political pop that many associate with Chinese art. Instead, these artists were interested in subtler, quieter political gestures that still played with loaded sites (like Tiananmen Square) and imagery (like Mao).

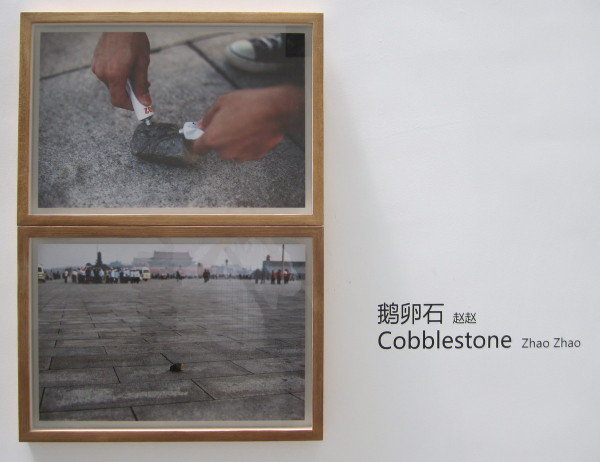

I loved this photographic documentation of an action by Zhao Zhao where he superglued a simple cobblestone to temporarily break the flat, cold austerity of Tiananmen Square. Full of loaded meaning and quiet protest, it was simple and profound.

Another simple yet evocative piece. In this video, three actors stand in as look-alikes for three generations of China’s political leaders. They run slowly in place, grimacing and sweating as if running through quicksand. It made history and politics feel like a cold, hard push forward with no clear finish line.

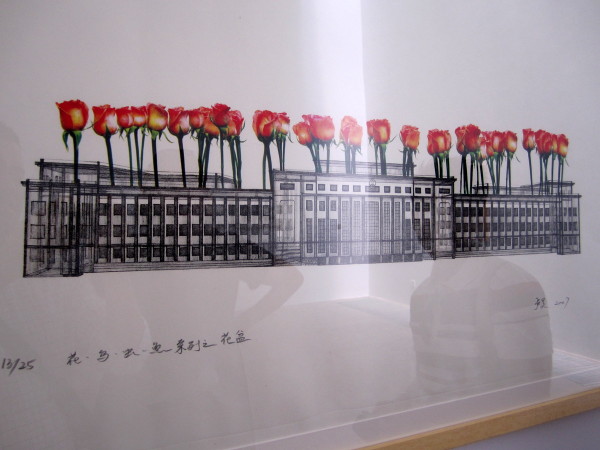

Lu Hao takes an official government building and turns it into a flowerbed. Can hope and beauty spring from repression? Or grow in spite of it? I sense that some of the most interesting art being made in China begs these questions, and deals with when art is or is not a subversive form of self-expression.

These “Stir-fried Tanks” seemed to reference the iconic image of the man in front of the tanks at Tiananmen Square. They were included in the “Rehearsal” section of the exhibition, bringing to mind military processions and public displays of power. I liked how as objects they deflated the violent machinery into clunky, strange gobs, haphazardly arranged instead of in an orderly line.

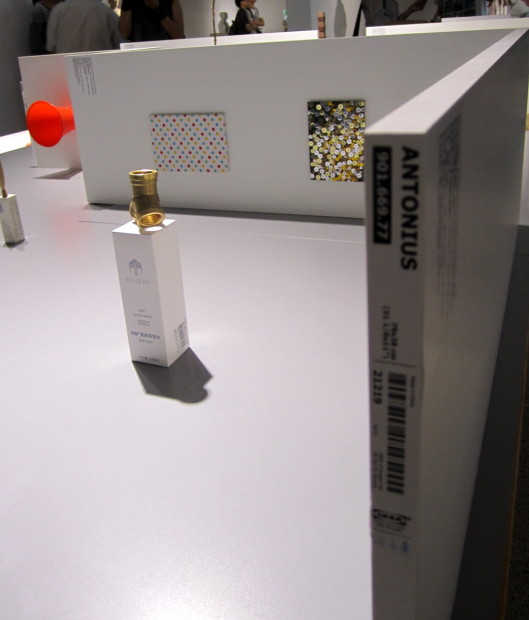

Because of our university affiliation at Rice, we also visited the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. We saw a student show of painting and sculpture, and one of the highlights was how the above artist made a mini-museum of iconic modern/contemporary works out of food, common knickknacks, and functional objects. It was lovingly made and completely irreverent at the same time. In the world of over-scaled, over-produced, and outsourced art, it reminded me that you don’t have to go to much further than your dorm room to make fun, ingenious work.

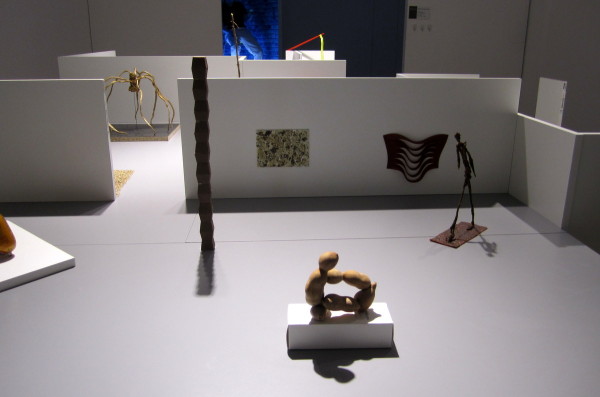

A peanut Henry Moore, beef jerky Giacometti, and something that looked like a fruit rollup made into a Robert Morris

Finally, there was a little time to squeeze in tourist attractions …

Seeing the Forbidden City was like being at the national mall in Washington DC and being surrounded by tourists from all over the US. In this case, I was surrounded by tourists from all over mainland China. The spectacle of sightseers trumped the sights themselves, as I could not get enough of the experience of groups in funny hats mobbing to look at a past that had been largely bulldozed in Beijing to build skyscrapers by “starchitects.”

Above is Rem Koolhaas’ famous building. It was surprisingly small when seen from up close, but it maintains a striking presence when seen from afar. Its open/irregular form was a relief from the rectangular bulkiness of many other buildings.

In general, Beijing is a fascinating mix of old and new. Our hotel was right next to a Ferrari/Lamborghini and Rolls Royce dealers, but you could also walk one block over down a hutong (alleyway) crowded with street vendors and dilapidated apartments. Old bikes, mopeds, and motorized carts clogged the bike lanes. But, of course, there was no shortage of Starbucks.