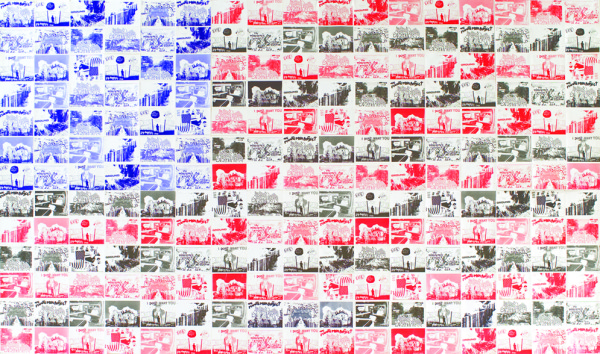

Juan Capistran, White Minority, 2006

The Exploring Latino Identities series examines issues in Latino/Latin American contemporary art through interviews with artists, art historians, and others. In this installment, University of Texas at Austin Art Historian PhD candidate Rose Salseda discusses Afro-Latin American identity and art that fuses punk rock, immigration, and post-identity politics.

Lauren Moya Ford: Your interest in identity extends to Afro-Latin America. How is black identity experienced differently in Latin America (especially in Mexico) than in the US?

Rose Salseda: In Mexico, for instance, the racialization process was more fluid and complicated than the “one drop rule” in the United States. Through miscegenation in the colonial era, racially mixed people of African descent could obtain certain privileges and mobility in Mexico that, say, a racially-mixed person of African descent in the US couldn’t. In Mexico, racial labels were abolished from national censuses and other documents in the 1800s. It was a process of erasure that parallels post-racial arguments being made in the US today. Since the Mexican government no longer accounted for people of African descent, their presence within national narratives dramatically diminished—nearly disappeared. Today, the black population in Mexico is most highly concentrated on the coasts of Guerrero, Oaxaca, and Veracruz; however, Mexicans who may “look” black might not identify as negro. That’s due to a number of factors: the erasure of history, discrimination against blackness, and even various understandings of what it means to be negro, moreno, etc. But, there are scholars and activists who are trying to increase awareness of Afro-Mexican histories and who try to rescue Blackness from negative perceptions. In the U.S., especially within the past decade, there has been an ever-increasing interest in Afro-Latino populations. Many Afro-Latinos contend with narrow understandings of Latino and black identity, especially when they encounter those with little knowledge about African diaspora in Latin America. As in Mexico, some Afro-Latinos do not or hesitate to identify as black as well. Groups like the afrolatin@ forum have been doing remarkable work to increase awareness of Afro-Latino heritage, experiences, and scholarship.

LMF: You’re an art historian who works with contemporary artists. What’s the relationship like between artists and scholars?

RS: Relationships between artists and scholars vary, so I’ll tell you about my specific relationship with the artist Juan Capistran. I first came across Capistran’s artwork in the Phantom Sightings exhibition at the Museo Alameda in San Antonio. I remember walking through the exhibit and immediately being captivated by a painting named White Minority. As a punk rocker and an art historian, I immediately recognized his references. Capistran’s artwork was divided amongst four panels that he staggered like the logo of Black Flag, a Los Angeles-area punk band. He also named his painting after one of Black Flag’s most controversial songs about race and he uses the song’s meaning and contradictions to re-imagine Frank Stella’s Zambezi (1959). I was impressed by the multiple layers of meaning embedded into his artwork and intrigued by the way that he used art historical and pop cultural references to critique the canonical visual language of Minimalism. So, I contacted him to learn more about his art and we began to work together. As an art historian, I try to honor artists’ interpretations of their work, but I also try to account for the other threads of information that come into play that artists may not immediately recognize, such as the ways that a particular artwork converses with another work, or with politics, social issues, etc. Also, one of the things I can offer as an art historian, to pay artists back for their time and generosity during my research process, is to expose people to their artwork through my writing and lectures. For example, I’ve conferenced on Capistran’s artwork at CAA (College Art Association) twice in a row and I will have an article on his work published next year. I also bring his artwork into the classroom at the University of Texas at Austin. For students to study Capistran’s artwork and learn its cultural, historical, and political significance is a huge achievement for me and is work that especially makes me proud.

Juan Capistran, Do You Want New Wave, Or Do You Want The Truth?, 2005-07

LMF: What happens when the artist and art historian disagree about the work?

RS: In the past, I mentioned to Capistran that I see his work as encapsulating particular Los Angeles-based sociopolitical histories. And, last summer, while I was recording an interview with him, he expressed several times that he was trying to have a broader conversation with his work. He told me, “I don’t want the conversation that I have to be a regional conversation. I don’t want it to be specifically about LA, California, the Southwest. The conversation is more global.” But I responded by telling him how I understand Los Angeles to be a global city. So, we definitely have points of departure, but we’re essentially getting back to the same ideas and goals. He informs my practice as an art historian; the process of peeling back all of the art historical and pop cultural references he makes exposes me to things that I wouldn’t necessarily have thought of if I wasn’t looking at his work. But, what I’ve written about him also informs his work and has made him re-evaluate his practice as an artist.

LMF: You’re currently working on an article about Juan’s work for a special issue of American Art that’s dedicated to post-identity. What does post-identity mean?

RS: Let me tell you what it’s not since there’s a lot of confusion about the term. Post-identity is not the same thing as post-race. Post-race is a discourse that dismisses the notion and value of race and racial identity. For instance, post-racial discourses often claim that race was a “problem” that has—somehow—been resolved and, thus, it is no longer needed today. In other words, post-racial discourses strive to erase the significance of race and the continuance of racial discrimination.

Post-identity is very different from this. It’s not an erasure of race or identity. Instead, post-identity is a hyper-awareness and criticism of the ways that race and identity have been used to limit the identities and opportunities of people of color, queers, and women. In the art world, it is a consciousness of how these things have been used to relegate brown artists, queer artists, and women artists into art “ghettos.” These artists are highly critical and skeptical of the ways that their art is labeled according to their ethnicities, races, genders, or sexualities because these labels often pigeonhole them, limit the interpretations of their artworks, and limit their access to broad audiences and markets. These types of polarizing labels also suggest that they make artwork that is unlike that of white, male, heterosexual artists—colleagues who make art that is never labeled as “White art” or “Straight art” or “Male art.” Yet, these same artists recognize the activism of their predecessors and the radical, positive changes it yielded. Post-identity isn’t a denial of the past, even though there is the use of “post” in the term. It is a practice, a consciousness, a critical mindset—it is not a particular iconography, style, or visual language.

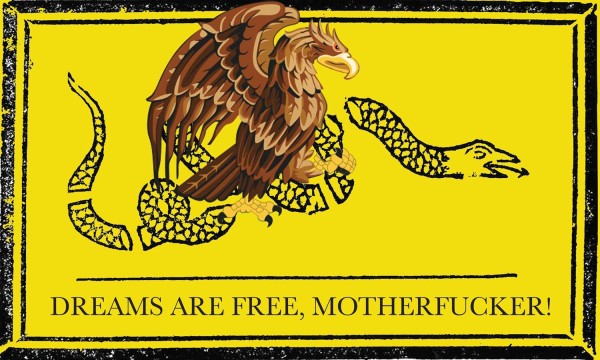

Juan Capistran, Dreams are Free, Motherfucker!, 2009

LMF: Earlier you talked about how a Latino artist brought punk into his painting. What’s the connection between art, punk music, and the Latin American/Latino experience?

RS: There is a lot of overlap between punk and art. When punk was gaining traction in Los Angeles in the 1970s, there were a number of people of color participating in it, especially Latinos. Artists were affecting punk culture and aesthetics and, at the same time, punk rock was affecting artists and their practices. In terms of immigration, Los Angeles’s early punk scene in the late 70s and 80s encompassed many musicians who were very critical of US imperialism in Latin America and understood the ways that the US contributed to circumstances that led Latin Americans to migrate. There were also numerous US punk bands in the 80s and 90s comprised of Latinos and Latin American immigrants who were sensitive to the daily experiences of undocumented workers. For instance, Willie Herrón, an artist who is well-known for his work in ASCO, a performance and conceptual art group he co-founded with artists Gronk, Patssi Valdez and Harry Gamboa, Jr. in the early 70s, was the lead singer and keyboardist of the early 1980s new wave band Los Illegals. “El Lay,” a song Los Illegals recorded in separate English and Spanish versions, was inspired by Herrón’s stepfather’s experiences as an undocumented worker in LA and the violence he encountered from la migra. There’s a deep, rich intersecting history between punk rock, art, and Latinos and Latin Americans. Scholars are just now catching up, uncovering and writing about this history.

LMF: Punk was the theme of the Met Ball this year… does that mean it’s dead?

RS: Radicalism is often pacified by mainstream culture through a constant neutralization of dissent. Perhaps, the Met Ball could be seen as part of this neutralization machine. Punk rock also seems to be an acceptable phase that young people coming of age go through now—sort of like a rite of passage. Despite these things, I still think punk rock is valuable for people today. It still has the ability to raise political and social consciousness through its music, lyrics, and aesthetics. I didn’t come from the original punk rock scene in LA, but I went through that rite of passage at an early age and I wouldn’t be the same person without that music in my life. No, punk isn’t dead. It will never die.

Rose Salseda is an Art History PhD candidate at the University of Texas at Austin. Her field of research is in Modern and Contemporary Art, with an emphasis on Latino, Chicano, and African American Art and a secondary research interest in African Diaspora in Latin America. She is curating two simultaneous exhibitions of Juan Capistran’s work called What We Want, What We Believe: Towards a Higher Fidelity that will open on January 31, 2014 at the Visual Art Center and the ISESE Gallery at the University of Texas at Austin. Her forthcoming article, “A Latino New Wave: Minimalism, Race, and Post-Identity Politics in Juan Capistran’s White Minority,” will be published in American Art in March 2014.

1 comment

I think the Black Flag title & picture work a bit better than the minutemen titles- the trouble there is making a painting as good as those minutemen tunes, which is a far more daunting task.

Maybe these give up more in seeing the actual objects, but I am unconvinced they live up to the music very well.

At the same time, few paintings by anyone are as good as minutemen tunes!