Various forms of crowdsourcing have been around forever, but no one really knew that they were doing it until 2006, when editors at Wired Magazine coined the word and defined it: “crowdsourcing represents the act of a company or institution taking a function once performed by employees and outsourcing it to an undefined (and generally large) network of people in the form of an open call.” Now, everyone is in on it, even museums.

Various forms of crowdsourcing have been around forever, but no one really knew that they were doing it until 2006, when editors at Wired Magazine coined the word and defined it: “crowdsourcing represents the act of a company or institution taking a function once performed by employees and outsourcing it to an undefined (and generally large) network of people in the form of an open call.” Now, everyone is in on it, even museums.

CROWDFUNDING

The most practical form of crowdsourcing is crowdfunding, through web sites such as Kickstarter and Indiegogo. There have been some success stories, such as former Scrubs star Zach Braff recently raising $3.1 million to make a film sequel to Garden State. Museums love fundraising success stories.

This week, the Freer-Sackler Museum (the Smithsonian’s Asian art) launched a $125,000 crowdfunding campaign to help pay for an exhibition called Yoga: The Art of Transformation. The thinking is that crowdfunding would work especially well with the yoga crowd.

As Judith H. Dobrzynski pointed out in her ArtsJournal blog, this kind of fundraising is tricky; public failure does not boost the confidence of future donors. About a year ago, the Hirshhorn Museum used Causes.com to raise money for an Ai Weiwei exhibition, setting a goal of $35,000 and got a mere $555. The CAMH fared much better than that with its “Bring Andy Warhol to Houston” campaign, but the $5,300 raised fell far short of the $32,000 goal.

Scanning the crowdfunding sites, there a number of success stories for Texas arts organizations. San Anto Cultural Arts, Austin ArtWheels, Blue Star Contemporary, and the Blaffer’s presentation of the Museum of Broken Relationships all exceeded their goals, but then their goals were more modest than those listed above. If a modest budget is the key, then what explains the “Let’s Build a Goddamn Tesla Museum” campaign? They set a goal of $850,000 and received $1,370,461. Maybe they got some momentum from a certain wackiness factor, but then that wouldn’t explain London’s UFO Museum, who only raised $370 of its $970,000 goal. Crowds can accomplish miracles, but they can be fickle.

CROWDVOTING

In another Dobrzynski blog this week, she reports that the Georgia Museum of Art has decided to let visitors choose which works to deaccession. They have five works by the French artist Bernard Smol (1897–1969) and have decided that they really only need one. According to the exhibition description (yes, it’s an exhibition called Deaccessioning Bernard Smol), “Visitors will be able to vote on which one they would like the museum to keep, and the curatorial staff will take those votes into consideration.” It then says the paintings are “of comparable dimensions, styles and significance,” so it’s too hard to decide what to sell “except for a difference in their exhibition histories and the ways in which they entered the collection.” Who needs fancy curators when the paintings just all look alike anyway?

When the Smithonian’s National Portrait Gallery got in hot water in 2011 over their decision to remove David Wojnarowicz’s 1987 video “A Fire in My Belly” from a group exhibition exhibition, a Smithsonian panel organized to study the controversy and “suggested that the Smithsonian provide an opportunity for the public to weigh in at ‘pre‐decisional exhibit planning phases.’” Robin Cembalest said in an ARTnews article at the time, “Opening exhibition preparation to crowdsourcing is not a way to anticipate controversy—it’s a way to assure it.”

CROWDSOURCING CREATIVITY

Okay, there are a bunch of pretty cool projects created through crowdsourcing, like Swarmsketch and the One Million Masterpiece. Learning to Love You More started up in 2002, posting assignments from artists Miranda July and Harrell Fletcher to crowds across the globe. July and Fletcher made crowdsourcing cool before crowdsourcing was a word. Aurora Picture Show Founder Andrea Grover, who has curated a number of crowdsourced exhibitions says that the collective spirit, the amateur’s passion, and relative anonymity of crowdsourcing makes people “more apt to reveal themselves.”

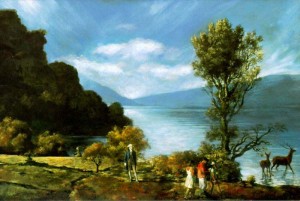

Komar and Melamid’s People’s Choice series (1994-1997) investigated crowdsourcing even earlier. The artists commissioned polling companies in 11 countries—including the United States, Russia, China, France, and Kenya—to conduct scientific polls to discover what they want to see in art. Intended to free the artist from the burden of creative authority and to mimic the democratic process, they believed that the public was an adequate judge of good art. But after many polls with the same generalized results (“the same blue landscapes”), they realized one side effect of overcrowdsourcing: “Looking for freedom, we found slavery.”

6 comments

Really interesting Paula, thanks !

Given your interest, I think that you (and the other readers here) would be really interested in some recent research that I have come across that theorizes about crowds and such similar phenomena.

It’s called “The Theory of Crowd Capital” and you can download it here if you’re interested: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2193115

In my view it provides a powerful, yet simple model, getting to the heart of the matter. Enjoy!

Interesting piece. I would only suggest that each of these manifestations of crowdsourcing functions in a unique way, so it’s difficult to assess the effectiveness of the practice as a whole.

You begin with crowdfunding, but one point not addressed here is how the size and nature of the projects and entities soliciting, as well as their preexisting access to funding affect the likelihood of success. There was quite a bit of noise made about Zach Braff’s solicitation, because the general assumption is that Braff already has access to producers and Hollywood funding channels. To many, this defied the spirit of crowdfunding– which has been the champion of the “underdog” independent creative community. Case in point, over $200,000 has been raised by unincorporated artists in Houston to fund projects through one crowdfunding platform, IndieGoGo, alone in the last year. (Kickstarter is undeniably the more popular tool, and I didn’t have the time or energy to determine that figure.)

That said, I find it peculiar that larger institutions would take to this method, when crowdfunding platforms are really only tools to amplify preexisting fundraising activities and are by no means a panacea. For an unaffiliated artist, they are a means to organize a campaign, galvanize public interests, and make a public appeal. But museums should already have these tools in place, so joining the crowdfunding community seems to a case of jumping on the bandwagon– or it may speak to a (mistaken) notion that there are people scanning crowdfunding sites, eager to find something interesting and desperate to part with their money. (Protip: they’re not.) On the other hand, a museum utilizing Kickstarter for a project might also betray where the project falls in the institution’s fundraising priorities.

I’ll use the local music group Two Star Symphony as an example: in the last 2 years, they have completed two successful crowdfunding campaigns- the first, a $7,000 to record some original compositions and the second, $5,000 to shoot a music video. In other words, a 4-person music ensemble raised funds tracking with the CAMH’s similar efforts and in the second instance, exceeding them. However, it needs to be stated that band member Jerry Ochoa has a development background and fundamentally understood the necessity to approach the IndieGoGo campaign the same way one approaches any successful fundraising campaign– by securing advocates at the outset, financial commitments before the launch, matching funds, etc. IndieGoGo merely provided the forum and framework for what are otherwise standard campaign activities.

When push comes to shove, I think crowdfunding has been fantastic for the indie creative community and hope it continues to be a useful resources for a group already struggling for access to funding.

Exactly. These crowdfunding sites have been great and often successful platforms for a number of individual artists and smaller arts groups.I think that people may be suspicious of larger organizations using these sites for the same reasons that there was a backlash against Zach Braff’s campaign. It might be summed up in the plea by Jon Lajoie in his Kickstarter parody: “Please help me accomplish my dream of becoming super rich, without having to compromise my sense of entitlement.”

Bingo.

Paula, you may have, in your research, encountered the Amanda Palmer story, but if not, I highly encourage you to watch the following TED talk: http://www.ted.com/talks/amanda_palmer_the_art_of_asking.html

But just as importantly, read the followup NYer piece about the backlash: http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/culture/2012/10/amanda-palmers-kickstarter-scandal.html

I think there are a lot of interesting takeaways from this narrative for any institution diving into the world of crowdfunding.

https://vimeo.com/67650725