Andy Coolquitt’s Attainable Excellence at the Blaffer Art Museum is divided into two distinct modes, as is his career. According to the 49-year-old artist, the two are converging slowly, as the market-friendly lamps and furnishings of his post-2008 oeuvre draw attention to the more complicated, abject installations and performances he pursued during decades of relative obscurity in Austin, Texas.

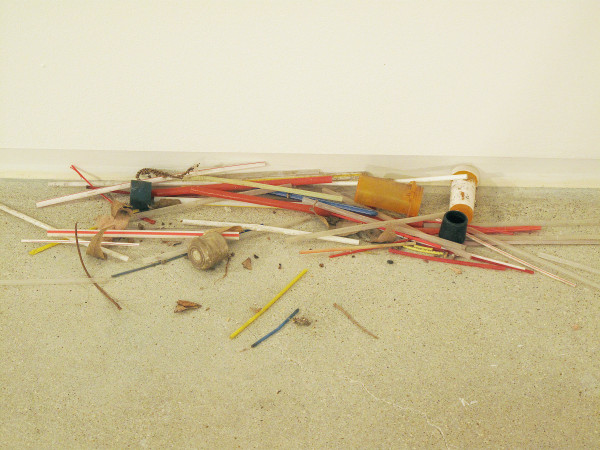

They haven’t merged yet. One of the show’s admirable qualities is restless improvisation; Coolquitt is visibly mashing-up several different modes of exhibit-making, albeit with mixed results. The Blaffer installation is an experiment in segregation: in the tall room, one wall is populated with a display of Coolquitt’s colorful, totemic rods and lamps, like the window of a retro-hip furniture store; by contrast, viewers entering the exhibition’s second act in the low-ceilinged space are likely to accidentally kick some of the installation out of the way. Negligible piles of soda straws, dirt and and detritus guard the entrance, and must be hopped over, walked around, or tread upon, immediately forcing viewers to re-evaluate their role in relation to the art on display.

They haven’t merged yet. One of the show’s admirable qualities is restless improvisation; Coolquitt is visibly mashing-up several different modes of exhibit-making, albeit with mixed results. The Blaffer installation is an experiment in segregation: in the tall room, one wall is populated with a display of Coolquitt’s colorful, totemic rods and lamps, like the window of a retro-hip furniture store; by contrast, viewers entering the exhibition’s second act in the low-ceilinged space are likely to accidentally kick some of the installation out of the way. Negligible piles of soda straws, dirt and and detritus guard the entrance, and must be hopped over, walked around, or tread upon, immediately forcing viewers to re-evaluate their role in relation to the art on display.

sarah sweep

It’s a gimmick, but it works. Coolquitt really doesn’t care what happens to his little piles of used coffee stirrers and pocket lint. They’re a stopper, casting into doubt the purposefulness and the inviolability of the more rigidly arranged tableaux in the room. But this is no interactive scatter-art show: the exciting indeterminacy suggested by the floor sweepings quickly gives way to arrangements of found and altered objects as precisely calibrated as ikebana.

Despite the mildly shocking scattered elements, the Blaffer’s second room is basically three major tableaux, all from 2010, embedded like plums in one of Coolquitt’s most sparse installations ever. A half dozen ancillary sculptures, wall objects and minute trash piles fill two-thirds of the low-ceilinged gallery, but fail to coalesce into an overall installation: with the showy furniture and lamps relegated to the other gallery, the most visually compelling objects are all locked into one tableau or another, and the tableaux are too self-contained and too far apart to operate in concert. They hog the attention and the gallery lighting, making the smaller elements, like the wax candles, the lava rock, the speaker wire, and the and a crumpled paperback copy of John Grisham’s The Brethren, into filler.

DWR Picture, 2010

The best of the tableaux is DWR Picture, a grouping taken verbatim from we care about you, his 2010 show at Lisa Cooley Gallery in New York. A weathered rectangle of framed Plexiglas flanked by seven leaning sticks reads like an Elmore Leonard novel-a story of boredom and failure laced with violence. Some of the sticks are broken tools, some improvised weapons. A three-foot closet pole wrapped with black electrical tape threatens, as does a five-foot length of molding inscribed with Sharpie: “DON GENERAL GANGSTA GREENEYES THE LAST OF A DYING BREED”! DEAD MAN WALKING -DONT LET IT BE YOU ON MY NEW VIDEO.” A bent broomstick printed with a pink giraffe pattern and a pink plastic floor mop lend freaky domestic pathos. In the center, a grizzled, tobacco-colored panel like Coolquitt’s beard or the Shroud of Turin, is framed behind Plexiglas: an unsanitary portrait, with motley acquaintances. Autobiographical?

The back story for all this assemblage is that Coolquitt searches the landscape for hideouts where crack smokers gather on cardboard mats and broken kitchen chairs to do their thing, leaving behind pathetic improvised living rooms, assorted trash, and the innumerable butane lighters that are a mainstay of Coolquitt’s work. Knowing this lends Coolquitt’s work a crime-scene cachet; bending over to analyze the rumpled, water-stained pages of a ruined paperback book, one wants rubber gloves and an evidence bag. For us non-crack smokers, it also becomes an exercise in drug-culture anthropology: why smoke crack outdoors? Why gather? Do crack users drink a lot of coffee, or lick a lot of lollipops? What do they do with all those lighters? A video produced by AMOA-Arthouse, the first venue for this show, shows Coolquitt tooling around Austin on his bike, scavenging materials for his art in a green landscape far different from the familiar shooting-gallery grit of east-coast drug culture vérité. The trash is scattered among bushes and along streams rather than dumpsters and alleyways, shady underpasses fill in for burned-out basements. It’s a Southern, warm-climate desperation.

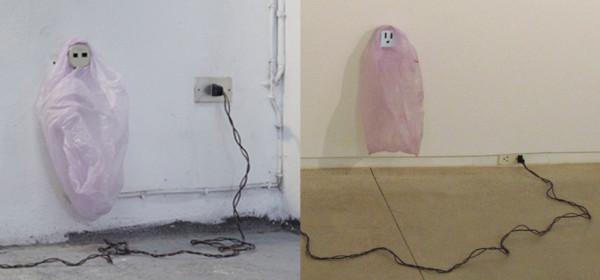

no, yeah, 2010

Coolquitt’s other tableaux, no, yeah and Memphis (Italian, Not Elvis), are reconfigurations of pieces installed in his 2010 show Curly Ellis at Zero in Milan, where they took advantage of electrical conduits and outlets in the space. Lacking these elements in the present installation, Coolquitt settles for less precise, less poignant versions of the same pieces, his formidable flexibility as an improviser hampered by the canonization of his work. no, yeah includes a fake electrical outlet made casually from blue foam, a bit of trompe l’oeil that is out of character for Coolquitt, in whose work things are what they are, relentlessly.

Details of no, yeah, in Milan, left; and at Blaffer, right

What’s best about Coolquitt’s work is the way his omnivorous scavengings are overlaid with a witty, razor-sharp formal sensibility. Through loving craftsmanship, Coolquitt strives to cobble a rehabilitated aesthetic from the remnants of a crap culture. Whether he’s carefully arranging trash, taping a bundle of sticks, or patiently upholstering a 2×4, Coolquitt’s caring, idiosyncratic hand evokes an image of the artist as world-mother. Despite their abject materials, Coolquitt’s lamps and staves are optimistic, with the funky charm of bake-sale cookies. It’s all about redemption.

It’s also about nostalgia. The 40-odd objects in Coolquitt’s lamp room form a neo-tribal, cargo cult shrine. Ceremonial staffs sport iconic objects from Coolquitt’s formative years in the 70s: a jumbo green crayon, kitsch-moderne coffee-table art, Newport cigarette boxes, a needlepoint flag keychain, garish polyester. Like a Mickey Mouse kachina, or Jake and Dinos Chapman’s faux-African McDonalds carvings, Coolquitt’s works look at commercially-inspired culture from the outside, combining nostalgia for praying ceramic hands, funky globular light bulbs and striped toe socks with violent rejection, expressed through breaking, re-welding, and reconfiguring. Many of the praying hands flip the bird with glued-on broken fingers. With self-conscious irony, Coolquitt reprocesses the cheapest mass-produced steel furniture into unique, handmade high-end decor.

It’s also about nostalgia. The 40-odd objects in Coolquitt’s lamp room form a neo-tribal, cargo cult shrine. Ceremonial staffs sport iconic objects from Coolquitt’s formative years in the 70s: a jumbo green crayon, kitsch-moderne coffee-table art, Newport cigarette boxes, a needlepoint flag keychain, garish polyester. Like a Mickey Mouse kachina, or Jake and Dinos Chapman’s faux-African McDonalds carvings, Coolquitt’s works look at commercially-inspired culture from the outside, combining nostalgia for praying ceramic hands, funky globular light bulbs and striped toe socks with violent rejection, expressed through breaking, re-welding, and reconfiguring. Many of the praying hands flip the bird with glued-on broken fingers. With self-conscious irony, Coolquitt reprocesses the cheapest mass-produced steel furniture into unique, handmade high-end decor.

Modernish, 2011 (detail)

Coming of age in 1979, Coolquitt is quintessential GenX, literally picking up the pieces of the baby boom. It’s no accident that he’s come to prominence now, after years of paddling his own canoe in Austin: the alternative world order he began crafting for himself in the 80s has, like Coolquitt, become the new mainstream.

Andy Coolquitt: Attainable Excellence is on view at the University of Houston’s Blaffer Art Museum through August 17, 2013.

Bill Davenport is editor of Glasstire, and is a connoisseur of trash, himself.

1 comment

Must see before comment, that is what I gathered from Bill’s article.