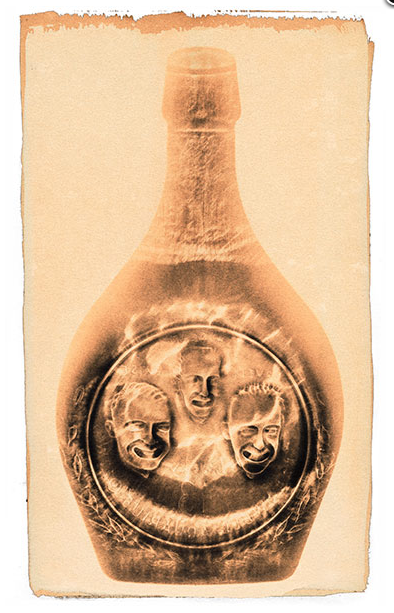

David Johndrow, Medicine Bottles, archival pigment print from cyanotype photogram

As Instagram portfolios overflow with images taken with ever-improving iPhone cameras, Austin-based artist David Johndrow continues to make platinum-palladium, cyanotype and gum bichromate prints, observing minute details that most of us overlook. Growing up in Houston, Johndrow became close with the late Bill Hicks, an uncannily hilarious, foul-mouthed and cathartic performer of comedy and social satire who remains an iconic influence on American culture and beyond. Johndrow and his photographs contributed greatly to the British-produced documentary “American: The Bill Hicks Story,” which premiered at SXSW in 2010. I caught up with the artist recently to ask about his latest goings on via email.

David Johndrow, Apollo 13 bottle (back), archival pigment print from cyanotype photogram

John Aasp: Let’s talk about your new work. Can you briefly describe what you’ve been doing lately?

David Johndrow: I recently finished a portfolio of cyanotypes made from my collection of glass objects. Now I’m working with gum bichromate. It’s a process I have dabbled with off and on for years with sketchy results, so I finally decided to take it seriously and really learn it and make the most of it. I’ve got to say, I think it’s my favorite printing process. As for my subject, I’m still shooting found subjects in nature—which could be anything from insects to flowers to simple textures. It’s been an ongoing thing and is something I will probably do for as long as I keep coming across interesting things. I spend a lot of time working outdoors, so I just have to be aware of my surroundings to find things to shoot. I’m still amazed that at 52 years old I constantly see things that I’ve never seen before.

JA: Lyle Rexer did a book in 2002 called “Photography’s Antiquarian Avant Garde: The New Wave in Old Processes,” saying that the included artists were confronting the “physical facts of photography” and rebelling against “the advent of digital technology.” Do you see yourself as part of that wave?

DJ: I don’t really feel that by using old processes I am rebelling against or rejecting digital technology. Although I still capture images on film, I use digital to make enlarged negatives and correct or enhance images. One of the great ironies here is that digital technology has, in large part, been responsible for the resurgence in antiquated processes. One of the stumbling blocks in contact printing—necessary in most older processes—is the negative. One used to be limited by the size and quality of the original negative. Enlarging them was very difficult and expensive. Now with digital negatives, you can make precisely sized and calibrated negatives on an ordinary inkjet printer. In the end, my answer to this ongoing debate is that there are no rules when it comes to making art. Whatever medium allows you to express yourself best is the one to go with. New media don’t invalidate old ones. Oil paint is a very old medium, but people do very contemporary art with it. It looks amazing, so people use it. Others prefer the look and feel of acrylics or inkjet. It’s pointless to politicize media. It’s the same as when photography was first invented and there were debates about whether it could be considered art or not. Now, that debate seems ridiculous.

David Johndrow, Longhorn Beetle, platinum-palladium print

JA: What about traditional and antiquated photographic methods do you think still compels contemporary viewers?

DJ: I think old photographic methods still compel people because they look great. For instance, metal salts on paper have an amazing look that can’t be matched by other mediums. Also, traditionally made prints tend to have inherent flaws that make the photographs more interesting. It shows a bit of the hand of the maker and makes things look more lively, less uniform. Another thing people like about the old processes is that a certain amount of craftsmanship went into them. These processes are labor intensive and take practice and skill. I think this gives the images a history and depth that resonates with the viewer.

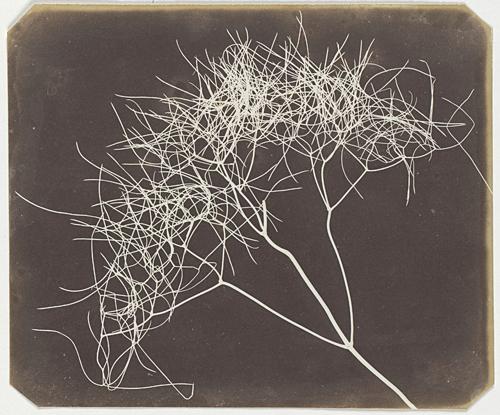

Wild Fennel (1841-1842) by William Henry Fox Talbot. Salted paper print. Gilman Collection, purchase, Denise and Andrew Saul gift, 2005 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

JA: You’ve talked about your work as being attached to your passion for gardening. It’s said that William Henry Fox Talbot’s images were inspired by his family’s interest in botany and gardening. Do you think there’s an inherent kinship between that study of nature and the photographic pursuit as Talbot, and later photographers like Karl Blossfeldt saw it?

DJ: Gardening, like photography, is all about paying attention to the details. Nature has so many dimensions. The closer you look, the more it reveals. To be a good photographer, you have to learn to see what’s really there, to see what the camera sees and not what you mentally project onto it. I think photography helps us see the world in new ways and is really an extension of our awareness.

JA: What led you to pursue photography at UT Austin? Did you learn anything that you still carry with you?

DJ: I started out as an art student and then changed my degree to film. I quickly learned that I wasn’t a very good collaborator, so I wanted to go back to making art by myself. I took a darkroom class in the art department and was immediately hooked. The first roll of film I ever shot, I processed and printed myself. I still get a thrill when I see an image magically appear in the tray.

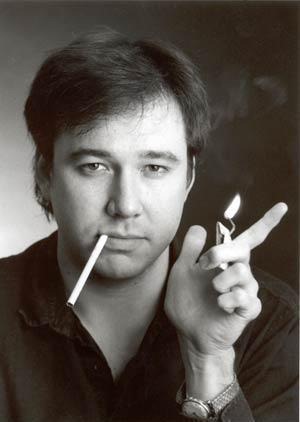

Bill Hicks, 1986, photographed by David Johndrow

JA: You grew up with the late Bill Hicks and took many photographs of him, and you’ve talked about how he encouraged you to pick up the camera. Do you find that your experiences with him still inform your work?

DJ: Being friends with Bill influenced my life in a lot of ways. He was so committed to integrity and honesty and in doing what one loves and pursuing it to the fullest. Meeting him was like a validation of things that I had felt inside, but was afraid to express openly. He was so bold and so honest about things that it helped me do the same. I think that to be a great artist (or anything really) you have to shed all of the ideas that society and culture instill in you and to forge your own path. His main message, for me, was to think for yourself.

JA: What do you think it is about Bill that still resonates so strongly with people?

DJ: Bill wasn’t afraid to speak aloud what people are feeling inside. Also, he was funny as hell. Humor comes from recognized truth. Maybe that’s why there aren’t any funny right-wing conservative comedians. But that’s another topic.

DJ: I only saw the movie once, at the SXSW premiere, and I enjoyed it. Of course, being so close to the subject, I thought it only showed a narrow view of his life and personality, but I think they did a good job with the slice they showed. I do think it’s weird that they called it “American” because Bill hated anything to do with national identity and patriotism. They seemed really into the idea that the Brits “got” him, when the Americans didn’t. Bill had a great bit about only being an American because his parents had sex here so it was a hard thing to be proud of.

David Johndrow, Ink Bottle #1, archival pigment print from cyanotype photogram

JA: How difficult is it to maintain control over your images? Do you think photography is perceived more so now as an expendable medium?

DJ: It’s harder now. Once something is on the Internet it can get away from you. Especially with my Bill Hicks photos, I’m constantly seeing people selling things with my images on them. I try to stop them when I can, but it’s time consuming. Fortunately, the copyright laws are still fairly strong and I have successfully gone after people and gotten payment for stolen images. People do still have a perception of photographs not really belonging to any one person. I’m not sure why. Maybe because it seems so easy and so derivative of the real world. It’s just seen as a copy of something, so copying it is ok. It kind of goes back to the original rejection of photography as a true art form.

“Photographers, you will never become artists. All you are is mere copiers.” – Charles Baudelaire, 1859 [cited in: “Camera Austria” 14/84, Annie Le Brun “The Feeling of Nature at the Close of the Twentieth Century”, p. 20] Photograph of Baudelaire by Etienne Carjat, woodburytype, 1878. George Eastman House.

DJ: I think all comedians have a problem with their material being stolen. I know it pissed Bill off, but he never went after anybody. He was too busy moving on to the next thing. Besides, it wasn’t the jokes themselves that were important, it was the way he performed them that made them great.

JA: Is there anything about Bill that you think remains misunderstood?

DJ: I think one of the things about him that is often misunderstood, and that sets him apart from a lot of other so-called “edgy” comics, is that he was not cynical. He hated hypocrisy and ignorance, but was a very hopeful, positive guy. Also, because he ranted against organized religion and various belief systems, a lot people assume he was an atheist. Actually, he was the most spiritual person I ever knew and we talked about God and the meaning of enlightenment more than any other topic. He liked to quote that “Blues Brothers” line: “We’re on a mission from God.”

JA: Do you think living in Texas has a particular effect on artists?

DJ: It’s probably just my biased view but Texas does seem to produce a lot of unique characters. People here tend to be very funny and idiosyncratic. Maybe it’s the wide open spaces or the crazy religions, I don’t know. I moved to California for a short period in high school, and the people there seemed so bland and staid compared to my friends in Houston. They didn’t seem to be as adventurous and curious. Maybe I was hanging with the wrong crowd. I did finally meet this wise-ass guy who made me laugh—turns out he’s from Houston too!

David Johndrow, Jim Beam Shot Glass, archival pigment print from cyanotype photogram

JA: What do you think about the project to create a statue of Bill in Houston? Would he be flattered?

DJ: I think Bill would be flattered. He was into being famous, or infamous, after all. I just hope they don’t give the statue a mullet—ha ha. We all had regrettable hair cuts in the eighties. You don’t want that set in stone. Then again, everything comes back into fashion eventually.