“Latin American countries are at a disadvantage in terms of research funds in technological fields. As a result, all sorts of equipment and devices are adapted and updated in a natural and unassuming manner, resulting in surprising innovations that are useful and remain well beyond their shelf life … The reason why the valence of Latin America’s low-tech proposal is so surprising is its versatility and poetics.”

— from curatorial statement by Maria Iovino

In Transitional, a group exhibition of young Colombian artists at Sicardi Gallery, curator María Iovino brings together artists with a closely shared sensibility. In black and white line drawings and low-tech sculpture/video, they tackle big ideas with a disarming simplicity and immediacy. In her provocative statement that is more theoretical than directly descriptive of the work in the exhibition, Iovino says she has seen over a decade of work by young Colombian artists and that she has “witnessed significant changes in the ways in which the world is considered and expressed.” New poetic gestures by these young Colombian artists offer a different lens through which to understand interpersonal relationships in a shifting landscape of technological, political, and scientific change.

Adriana Salazar’s kinetic sculptures are probably the most concise and alluring poetic statements using low-tech mechanisms. Moving Plants No. 27 is as simple as it gets, two dried plants stand upright on their stems, each dead plant stuck on a small motor with a rotating gear. They slowly follow different circular paths, as they nearly collide with one another at one point. It evokes a dance between two lovers, and the technological desire to prolong or resurrect life. Perhaps a kind of heartbreak exists in the space where the plants’ frail petals nearly touch, yet if they touched would the dry petals shatter and destroy each other? Such a grandiose romantic reading is deflated by the piece’s absurd, anti-monumental quality. The placement on the floor without a pedestal, as if they grew from the gallery’s concrete floor, and the very visible plugs and wires is a nice decision to not obscure the piece’s inner mechanisms.

Adriana Salazar, Samba (Ed. of 3), 2010, motors, nylon wire, pulleys, and shoes, courtesy Sicardi Gallery

Salazar also animates a pair of worn black high heels to perform a clunky dance. This piece is more comic and absurd with a lot more hardware in the form of fishing line and jangling metal. I love the randomness of how the shoes patter around, and the humanity of the missteps. A machine could probably be programmed to execute a perfect samba, but this feels like a much more honest portrayal of an awkward marriage of the human with the robotic/technological.

Another standout in the exhibition are Diana Menestrey’s short animations about dynamics of cooperation, competition, and survival. Lasting no more than 30 seconds, Menestry’s anonymous characters look like animated pencil drawings of outlined figures engaged in some kind of momentary struggle. Two characters on a different side of a door anxiously try to open the door by both blindly pulling the handle. The door remains sealed shut as the characters try to reach each other and work against each other at the same time. In another video, two children submerged in water push one down to propel the other up to get a breath of air, as the view slowly zooms out to show the children in a glass of water with a slightly creepy music box soundtrack in the background. It is ambiguous as to whether they are helping each other or fighting for individual survival. As a whole, the videos are ambiguous visual proverbs and can probably be deciphered many ways. Because of the subtly of the animated gestures and the sound quality, they take on a heightened emotional resonance.

Cesar González, Modelo No. 3, 2012, adhesive vinyl and ink on wall, MDF polyhedron, courtesy Sicard Gallery

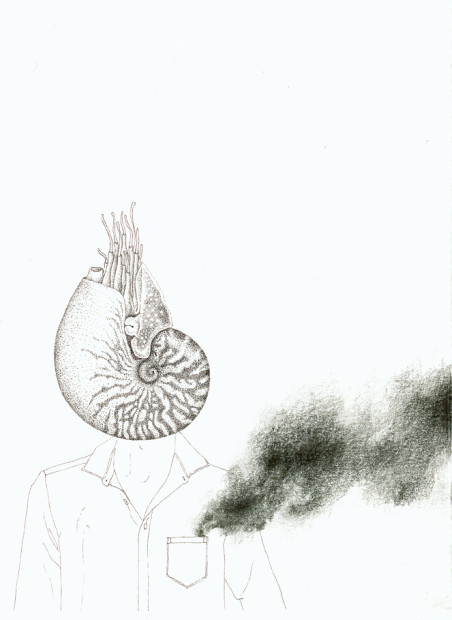

Outside of this work, other artists in the show exemplify Iovino’s view of a changing future in more illustrative ways through drawing. The blurring of the nature/culture divide is the theme of Teresa Currea’s suite of small and exquisitely executed drawings and collages where figures are caught in surreal, whimsical scenarios. In My Best Friends are Online (2012), old looking televisions, boomboxes, medical devices sprout arms and a plant head, as one figure in plainclothes photographs them. In another drawing, a man in a scuba suit tends to a fire hydrant spewing foliage. They have the paradoxical look of retro-futuristic, cartoons that point backward and forward at once. Cesar Gonzalez covers a wall of the gallery with small, sketchy figure drawings in vinyl, black ink, and gold leaf. Silhouetted characters huddle over desks or fly through the air as they appear to be dreaming up new architectural structures or testing out future inventions. It reminds me a little bit of a whimsical version of Leonardo Da Vinci’s Vitruvian man mixed with Buckminster Fuller’s musings on geodesic domes.

Luisa Roa, The Elephant Journey, 2012, sound installation and ink on paper drawings, courtesy Sicardi Gallery

Luisa Roa’s wall installation consists of pen and ink drawings hung at varying heights in a field of speakers with dangling wires, whose graphic quality echoes the strong thread of drawing that runs throughout the exhibition. The speakers pipe out the sounds of birds and a flowing stream. The drawings are abstract amalgamations of sea/plant/animal/earth forms breaking apart and dissipating into patterns of cross-hatched and curlicue lines. They suggest the interconnections of eco-systems as things like pollen and invisible matter spread to connect organisms in a constant cycle of flux and change.

Luisa Roa, The Elephant Journey (detail), 2012, sound installation and ink on paper drawings, courtesy Sicardi Gallery

Colombia itself is in a transitional state as it finds new economic prosperity. Sometimes wandering around big art fairs, such as The Armory Show in New York, I wonder about art and national identity. Maybe it is just the experience of a fair, but booths from all over the world can blend and merge together. It seems with the Internet, mobility, and artists being from somewhere but educated/working elsewhere (about half of the artists in the Sicardi show were educated or live in Europe), contemporary art can fall into a kind of “global” style. Iovino’s radical proclamations in her statement make me wonder if perhaps she overlooked the basic premise of how grouping artists by nationality may lean on an older (maybe less radical) category of identity in the age of porous borders, communications, and relations. The grouping may have more to do with proving how Iovino sees Colombia than the artists themselves, but that said, the exhibition does nothing if not make me want to see more of what young artists from Colombia have to offer.

Transitional at Sicardi Gallery is on view until March 16, 2013.