I appropriately write this on “Small Business Saturday” and artists and galleries are among the smallest businesses around. But, as I say in the essay, few seem to know how this small business works on either the production or marketing sides. In my art education no one ever told me and I’m willing to bet that business or dental college didn’t either. So, I call it:

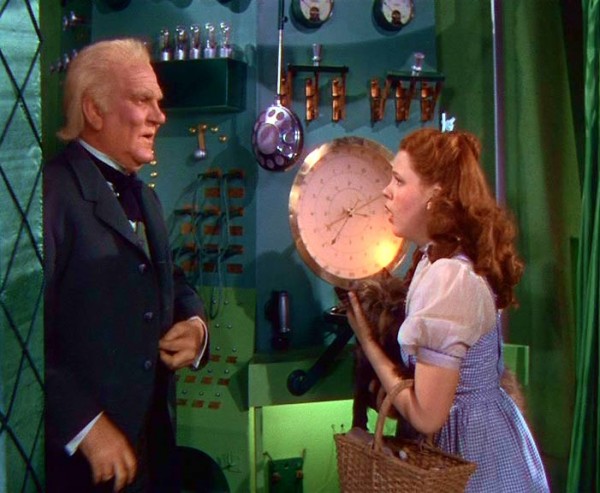

“Ignore the Man Behind the Curtain”

Many years ago, at a Texas Accountants and Lawyers for the Arts (TALA) workshop, a lawyer in the audience was amazed at the most common business practices of the visual art world. The lack of contractual obligations was merely the first of many revelations to most of the legal and accounting professionals attending the event. Since it was common knowledge within the art world, it seemed odd at the time that these professionals were so surprised by the commercial practices. But, since there is no transparency in the business of art, probably many of the practitioners (especially the younger ones) and most of the consumers of art don’t have such information either.

First we have to agree on the fact that Art is a business activity. It has many concerns beyond the business, but never forget that it is a commercial activity, at all levels. The recent due(l)(t) of Art Fairs here in Houston should have convinced even the most altruistic of us of that fact. Money is made and lost; who gains or loses depends on “whose ox is gored”. If we agree on this initial fact then we can explore how it works.

But first a question (directed mainly to the consuming public), how many artists who live and work in Houston earn their living solely from the making and sale of their art? It may surprise many that you won’t need your toes to count them, probably not all your fingers either.

Making the art is a given, artists make art because they have to, it’s more addictive than any of the drugs that they may use to relieve the pressures of the profession. And it’s not an inexpensive addiction either; I estimate that most artists spend at least 40% of their GROSS income (from whatever source) to make what you see.

Once the thing is made it becomes a marketing problem; the initial assumption is that it’s simply a matter of going to a gallery and having an exhibit. Fame and fortune follow, along with the rock and roll lifestyle, and the social dissipation of the traditional Bohemian existence.

But,

There are far more artists, making wonderful work, than all the galleries, alternative spaces, museums, or art consultants in town can possibly exhibit or offer for sale. The next obvious question is: How are the artists who are exhibited chosen? Remember, art is a business – if the dealer doesn’t have a base of collectors who implicitly believe the gallerist, no matter what the product, they have to choose work that they hope they can sell. The “art-ness” of the work is strictly a secondary concern to keeping the doors open, the lights on, and the dealer’s lifestyle maintained. This is not to say that the dealer doesn’t have an individual, personal, nurturing and continuing relationship with the art and artists they represent; but the initiation of the relationship is based on a strictly business judgment rather than only an aesthetic decision.

This business decision is based on many concerns: Does the artist have a history of sales and a collector base? Does the artist have “art institution” support? Is there a positive “critical” history? Are the prices the artist commands high enough to guarantee limited sales will support the gallery? Does the artist have a high enough profile in another context to generate sales? Does the work “fit” into the gallery’s profile? Do the prices fit the demographic of the gallery? It is the “Catch 22” situation that nothing succeeds like success.

But,

Assume that the artist is fortunate enough to garner representation, how is the business conducted? First off, there is a tremendous difference between a “dealer” and a “gallerist”. A dealer “makes the market” and expands the opportunities for the artists they represent, a gallerist sells things to whomever walks into their space. Most of the galleries in Houston actually fit both descriptions, depending on that month’s exhibit and irrespective of the prominence of the artist.

But,

The artist was paid for the art before the exhibit, right? Just like the shoe store on the corner, they had to buy their inventory. Well that was the way it used to be 150 years ago; in my 36 years in Houston only ONE gallery EVER owned all their inventory and Gerhard Wurzer died years ago.

So,

Assuming that you are a potential collector and you walk into the exhibit, how does the business proceed? There is a price listed somewhere, either on a wall label or a price list. That is the MSRP of the gallery. Depending on your status as collector, or if you are a frequent buyer, you may be offered a discount, since a prominent collection is a spring board to sales to other collectors. Owing to the present economic situation, galleries are more amenable to discount a price and, in the best of all possible worlds, the gallery absorbs the discount, usually both the gallery and artist share the discount, often it is only the artist.

But,

What does that mean to the artist? Your motivation may be to support an artist that you are familiar with, or friends with, or consider a viable investment; how much of that purchase price can you assume goes to the artist? In truth it varies, an artist who has a “international” or even “national” reputation and sales will get a larger percentage, but the artist who needs it the most will be lucky to get 50%. For their 50% they will have to support the cost of production, perhaps framing (sometime the gallery will provide this, but not often), and the “overhead” of operating a studio. Profit can get pretty minimal; the larger the discount, the smaller the artist’s potential profit. Strangely, sculptors sometimes get their cost of production “off the top”, since the foundry casting process is so expensive.

Now,

The artist has made a sale, HOORAY! but, the gallery has the money and very few cut the artist a check upon the sale of their work. Many galleries, depending on the gallery and the “informal arrangement” they have with the artist, keep the money derived from the sale for an indeterminate period of time. Remember, there are very few galleries and artists that have an actual, written and signed, contractual responsibility to each other. I have anecdotal evidence of galleries owing artists five figures for months, but sometimes this is because the artist is trying to help keep the gallery stay open. But, generally, it is to maximize the gallery’s profit margin. Again, remember this is a BUSINESS.

So,

What do you as a consumer and collector do to minimize your expenses? Or as an artist who needs the mortgage payment this month? One of the first actions is to cut out the middleman and go directly to the artist. This has some unforeseen ramifications: if the artist sells directly to a collector, they are usually responsible to share the purchase price with the gallery, depending on the agreement (perhaps contract) with the gallery. If the artist sells “out of the studio”, especially with a major discount, and does not give the gallery their share, invariably the gallery will learn about it. I’m sorry, but those of you who are collectors are notoriously prone to brag about the “cheap” work you got from (substitute your favorite artist here) and “loose lips, sink artists”. Desperation often leads artists to abrogate their responsibility, only to lose the representation they need. There have been artists in Houston who have done this and survived, but not many. If you can’t trust each other it’s tough to keep an active relationship (it’s like cheating on your spouse that way, you may still love ’em, but you just can’t live with them).

Similarly, an artist may have a geographic restriction on how many galleries, in what area, they can exhibit in without an agreement between the galleries. Ambitious young artists sometimes make that mistake, and, again, collectors will let the secret slip to the “primary” gallery. However, sometimes geographic separation will generate sales; anecdotally, I know of collectors who will not deal with a particular local gallery and prefer to buy the same work at a gallery in another city.

But,

Remember this is a BUSINESS!

And,

How does an artist gain the representation they seem to need, or at least exposure to the public, without conforming to a gallery’s “format” or other, more destructive, compromises? And, how does a collector, with altruistic intent, find art that speaks to them and artists they would want to support?

Well, first off, REMEMBER this is a BUSINESS, a “quid pro quo”. Both producer and consumer have to work at it. I’m pretty sure that the internet isn’t the answer, but it might help both sides. Personal contact and “networking” is more pleasant, especially over a drink.

Talk amongst yourselves. Artists, talk to people about collectors and share information, you could even tell a collector about someone else that they might prefer to yourself. Bert Long once compared the Houston art scene to a “basket of crabs, as soon as one gets to the lip of the basket, the others drag him back down.” Art as a business isn’t a zero sum game. Make that which is most important to you, not “what sells”. Someone will like it, don’t overprice your work, but don’t starve yourself either.

Collectors, ask artists leading questions; artists LOVE to talk about their work, if it seems interesting, go visit where ever the work is, gallery or studio. The studio may not be an upper-class showplace like the pristine white walls of the gallery, but generally you won’t get cooties. If you like something, buy it, if you don’t like it, that’s OK. Probably, someone you know would like it, tell them about it. Talk amongst yourselves and compare your experiences with artists and galleries, and realize artists’ prices amortize their materials, time, and experience, they’re not just gouging you.

And to quote the Bard, “To thine own self be true.”

& Let’s be careful out there.

9 comments

Maybe thems that buy art need to get cozy with the term “consumer”, and forget all about the wannabe implications of that other bullshittier term: COLLECTOR.

Good article Butch. I left the gallery scene in 1981 after being with three of the best gallery’s in Houston during the 70’s. I got tired of the “business”, 50% take on sales, and lack of transparency. I could not find a dealer that would agree to a three signature contract based on a sale between gallery, artist and client. An artist never knows what the work actually sells for, or why the discount should always be shouldered by the artist. After a while you find you are supporting the gallery, and not the other way round. I’ve done fine without them the past forty years.

Indeed. Art & business work well at the macro level, but on the micro level are a disaster. So many artists and administrators don’t spend the time needed or care to understand contracutal regulations as they relate to the arts. Just today I was reading commentary from an artist about “supposed” copyright. Just to verify, sending yourself a copy isn’t going to cut it in a court of law.

“I’ve heard about a ‘poor man’s copyright.’ What is it?

The practice of sending a copy of your own work to yourself is sometimes called a “poor man’s copyright.” There is no provision in the copyright law regarding any such type of protection, and it is not a substitute for registration. http://www.copyright.gov/help/faq/faq-general.html#poorman

Nice primer of the gallery/artist/collector ecosystem as it works in Texas.

There are other dimensions to the business of art, though, that are important and are becoming more important, especially here in Texas, far from the hub of the big-money art world. I suspect there may be more money circulating through the nonprofit organizations/artist/donor ecology than through commercial galleries.

Likewise, there is more and more art being marketed via non-gallery channels, and more and more art supported primarily through grants, prizes, and direct donations both private and public.

Good point, Bill. I think you are probably right, at least when we look at large non-profits like the MFAH and the CAMH and the HAA. But the thing is, we can only assume this. We can, to an extent, look at the finances of any legal non-profit (just go to Guidestar.org and look at their 990s), but we can’t do the same with privately owned galleries. It’s easy for us to learn that the HAA’s revenue for the year ending July 2011 was $7.1 million. But we have no idea what McClain Gallery’s revenue is, much less its net income. So we can only guess what the relative sizes of non-profits and private for-profit businesses are.

Great article for anyone involve in the art world.

I’ve found that teaming with a gallery can work very well. But, it is like finding a good spouse. I “dated” several before I really understood the due dilligence is involved in the relationship. I guess it might be true that you have to kiss a bunch of frogs to find that prince.

One of the exciting thing I have done is take an interest in the development of collectors. We make a real effort to invite younger people to the openings. The are often intimidated by the whole scene because they don’t know much about art. I like to engage groups of them at the openings and take them around and explain my art and what I am doing. We talk about collecting at an early age and buying what you can afford. I stress that it doesn’t have to be my work. But, I’ve had the pleasure of selling many people there first piece of original art. It is as exciting for them as it is for me. Invariably I hear from them later and that they have bought more art from other artists. It becomes a lifelong compulsion. This is a great way to build the art world for all.

I find this article’s writer rather naive, though trying hard to convey a nebulous art market…

The art world will swallow anyone without a sense of self-worth. I am the owner of a very well-known gallery and I can assure you that my artists were treated with dignity, respect and appreciation for their work. If I ever carried anyone’s work, I felt compelled to buy a piece from the artist. Kind of like putting your money where your mouth is. No platitudes, only the truth. I was, indeed, ruthless with any artist that lacked the commitment and love for his work. I had one artist, Truman Marquez, that sold a very expensive piece outside my gallery. I never said anything. A month later, I got a check from him for half of the sale. He earned my respect before, but he had my heart then.

Yes, I promoted their work equally. I called my clients who were, indeed, collectors. I had a newsletter that informed my clients (5,000) about the events of my gallery. I held about four shows a year and one special show for introducing new artists.

I filmed a documentary that informed new artists what to do to promote their art and invited a premier artist as a speaker. It was evident that they left that show with an armful of data and information to launch a successful career in art.

I had only one artist whose integrity was compromised due to his avarice and as usually happened, I spoke up and terminated not only a friendship, but the business relationship. He went on to live his life and I did too…nothing lost.

I have filled my life full of wonderful artists that are creative, tireless and some with avant garde inspirational ideas of art that ended up in SOHO and many who continue loving what they do, because as we all say, ‘It is our passion.’\

Our artist/gallerist relationship was based on mutual respect, knowing that having a gallery that promotes your work validates your commitment, understanding that I was in business because of them, and they had a loyal following because of my efforts. It has been the most beautiful experience of my life. My artists (those that survived me) became my second family of choice.

I have never regretted the artwork I purchased from any of them. Every art piece is a story of a wonderful person mindful of their love of life and appreciation of their own work. That in itself is powerful.

Meredith has laid the foundation for understanding MANY of the responsibilities and pitfalls. The following responses bring forth the ramifications of our diverse experiences: positive, neutral and negative. Having experienced dozens of relationships with galleries, and having started a few co-ops, I remain committed to being represented by galleries. Yes, these are business/marriages where chemistry of expectations and responsibilities must be shared. When I started this obsession, galleries took a third and some made money. Somewhere in the late 50′ – early 60’s, Marlborough-Gerson Galleries started advancing major artists substantial stipends in exchange for 50% of sales. The die was set. Nearly every gallery jumped to 50% of sales and then discounts without the promotional heft that Gerson brought with his advances/stipends. Even had a gallery that paid only 1/3rd. But, they bought the work. It was truly the gallery’s inventory. Some dealers have purchased work from me even after separating the representation. The definitions of dealers and gallerists is far to loose to be meaningful. Have tried being contractual but there was always strain. Yes, gallery representation is a business built on mutual trust and love of art.

Great article and responses. It’s hard for an artist to think of themselves as a business but they have to come down from the clouds once in a while or the IRS will help them. Have never understood why The Business of Art is not taught alongside the creating process.

I am basically self taught and have worked in the business world for many years as well. I have owned a gallery as well as being represented BY a gallery over the span of 40 years as a practicing artist. I have had my bumps along the way with gallery relationships but more than not have had great relationships beginning with Paint Box Gallery on Westheimer in the ’70s and Erdon Gallery on Lovette also in the ’70s. The story of my joining Erdon is a joyous one for me. All in all it’s the artist’s responsibility to act and practice good business and fairness ie not selling out of your studio if your gallery is in town etc and if they are make sure they know of the transaction, if the gallery did not send them the client, and give them their commission.

I have been represented by many galleries over the years and presently. I find that relationship to work the best for me as a painter as I can relax and produce my work while giving the sales over to someone else who will hopefully also help to promote me.

Best thing an artist can do is have their own consignment contract if the gallery does not and spell out all the money’s arrangement agreed upon!