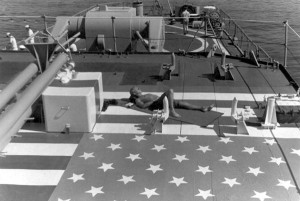

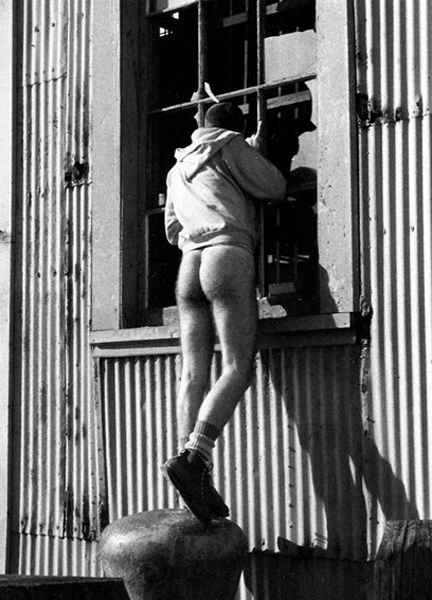

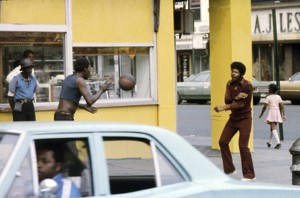

Alvin Baltrop’s photographs, most of them taken at the Hudson River pier between the 70s and 90s constitute the CAMH’ s latest Perspectives exhibition: Dreams Into Glass. They form a rich text that was sadly overlooked at the time of its making. The photographs depict, among other things, the cruising scene of the 70s, daily life in a poor neighborhood, dilapidated spaces, hustlers and whores going about their business.

Whores used to sing me to sleep. I grew up in what was once a suburb for affluent families. By the late 80s it had started shifting into the party district. By the late 90s clubs, bars and brothels outnumbered the residences. At sunset, the prostitutes and their bright jangliness would flood the streets, and throngs of clients would come up the hill or down the mountain to meet the nightly deluge. I have oddly tender memories of this clockwork miracle of lust, poverty, and need. In my bedroom, bars on the windows, a hundred feet from the gate, I fell asleep to the sounds of prostitutes haggling, laughing, fighting, screaming.

Alvin Baltrop’s pictures take me home. I want to say, “street recognize street,” but I was a rather staid catholic boy back then, and besides this is nothing to do with authenticity, too often a handy refuge for solemn mediocrity. It’s about effectiveness. Dig? How well can you communicate your understanding? How good are you at translating this life into that medium? Baltrop has me straight haunted by streetwalkers past and quite probably passed. The photographs themselves don’t lament and they don’t moralize, they deal in precision and beauty and so their evocative powers are immense.

The prints are small (more 291 than Yossi Milo) and they are imperfect (smudges, stains and cracks are evident) and even though this flies against our expectations for a contemporary photography show, they never feel amateurish. The work is greatly aided by some intelligent exhibition design. To be clear: Valerie Cassel and her curatorial crew clarify the feeling of the work; there’s no need no amplify what is already present in these images. The walls are painted in dark tones, strangely reminiscent of the type photography mattes one would find at Hobby Lobby. The net effect is that the space evacuates expectations of “good taste”, yet the somber colors and lighting design let you know that the pictures are still playing for keeps. The prints are arranged along intuitive structures that are difficult to describe but evince a fluidity of ideas and feelings that is hard to deny.

The first wall of the exhibition is masterful, it moves from Baltrop’s time in the Navy to his return to Brooklyn and end with an early picture of a dune at The World Financial Center. That last one would not feel out of place in an exhibition of prints from the Stieglitz and Strand era. I see a record of a life expanding, contracting and finding purpose in curiosity. It’s also a nice reminder of the kind of pop that modernist gestures can still bring to contemporary concerns.

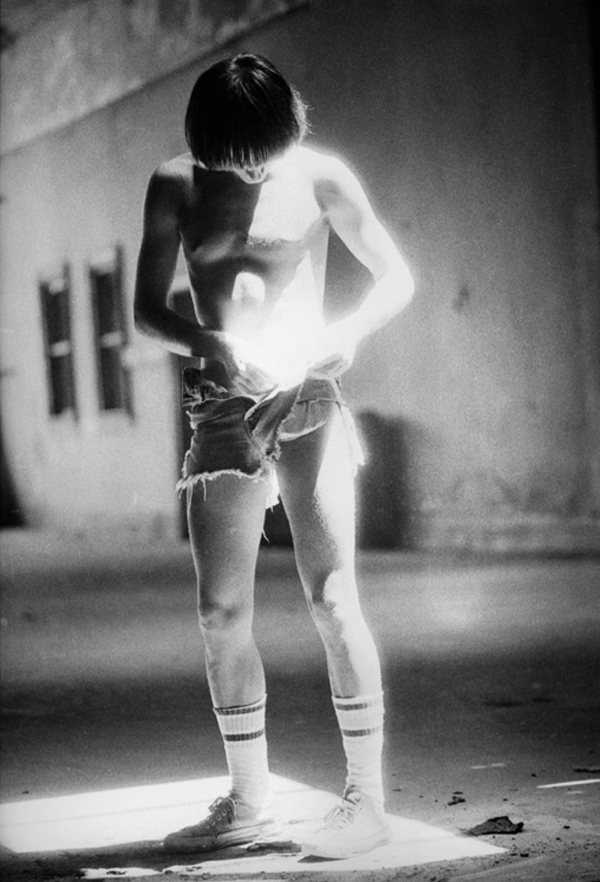

The placement of the three self-portraits is devastating. If we follow the show’s layout, we first come across a portrait of Baltrop in hospice near the end of his life. The picture is a glance, a chilling admission of frailty after the straightforward, almost confrontational nature of what’s come before. The next two are nudes of a teenage Baltrop, confident in his presence and his sexuality. Encountering end-of-the-line Baltrop made me wince, but encountering young-and-vital Baltrop, after walking around for a while with the frail version still on my mind, wounded me.

It is perhaps unfortunate that the most graphic images from the show are relegated to the room at the back. It gives the whole enterprise a bit of a 24 hour Newsstand feel, but without the sense of irony. No one thinks that you are going to the 24 hour Newsstand to get a sun bleached copy of USA Today, the front room is a cramped hodgepodge of media no one really cares about, while the back is a spacious and carefully curated porn palace. The layout has nothing to do with shame, but is rather a joke about shame. I wouldn’t exactly call Dreams Into Glass’ backroom shameful, but it does create space for the sentiment, and that is a notable misstep, especially in an otherwise well-calibrated exhibition. Still, I must give props to the CAMH for showcasing so many lovely pictures of genitalia. Charming images of cocks and cunts are a sure sign that a culture still cares about life.

Alvin Baltrop died of cancer in 2004, and now he is an emerging artist. Does this sound like a joke about artworld categorizations? It is. Beyond the yuks, the content and quality of Baltrop’s photography turn the lateness of his arrival into something considerably more troubling. Was it the luck of the draw? Possible, but I don’t see anyone else from that era filling that niche, and it is not as though Baltrop was not persistent. Randall Wilcox who handles Baltrop’s estate has made several references to the New York artworld’s ugly antagonism towards Baltrop. No names or specific instances are mentioned, but it doesn’t take much to imagine one of the gatekeepers thinking “Black and Queer! Well we must have limits.”

The possibility of a Baltrop being kept out of the dialogue in a systematic fashion is sickening. I grew up a film buff in a country without a film culture. Or so I thought. In The Agronomist, Jean Dominique talks about Haitians so sparked up by the innovations of the French New Wave that they took their cameras to the street. By the time I was born, Duvalier had eradicated so much of our cultural output, dictators fear ideas that they don’t control, that there was nothing left. Not even a stain. Maybe Baltrop and his New York adventures are easier to accept now that they exist solely as flashback. We should be grateful that this history was not bleached out, but we should remain wary. Who is being kept out today for being “too much?”

Dreams Into Glass closes this Sunday, October 21st.