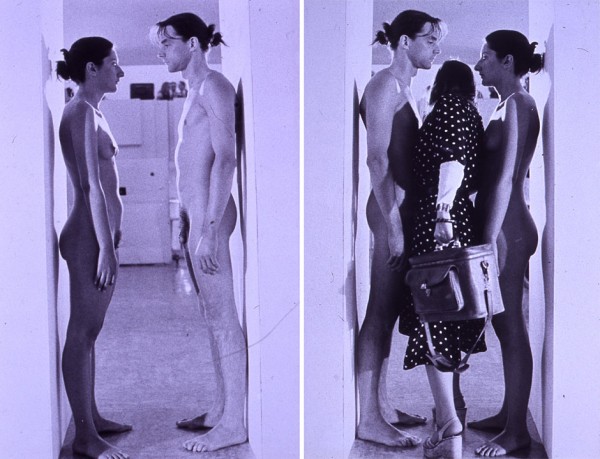

“Imponderabilia,” 1977, Performance; 90 minutes, Galleria Comunale d’Arte Moderna, Bologna, © Marina Abramović

Director Matthew Akers screened Marina Abramović: The Artist Is Present (2012) before a packed house during his Austin stay as a Texas Filmmakers’ Production Fund juror. While detailing the internationally acclaimed Yugoslav-born (1946) artist’s past, the HBO documentary charts not only the time leading up to the eponymous retrospective exhibition and new performance in 2010 at MoMA but also the three-month run of the show, which in addition to photographs, videos and artifacts encompassed reenactments of solo and collaborative works performed by thirty artists chosen and trained by Abramović.

Ulay, Abramović’s partner in love, life and art for a twelve-year period ending roughly twenty years prior to the documentary’s making, recounts encountering her on their shared birthday (November 30) in Amsterdam in 1975. He says, “I cared for the wounds”—those resulting from her auto-destructive performance (for which she carved a star into her abdomen and whipped herself). As Carin Kuoni points out in her introduction to Words of Wisdom: A Curator’s Vade Mecum on Contemporary Art, amongst the roles implied by the term “curator” is “caregiver.” That the production pivots around a shift between Ulay and Klaus Biesenbach, MoMA Curator, as the primary others in Abramović’s artistic realm complicates conceptions of curator and artistic collaborator—and ultimately beckons the question, “who truly is licking the artist’s wounds now?”

Imponderabilia, performed first in 1977, featured Ulay and Abramović standing nude in a doorway with enough space between for museum visitors to pass sideways only—thereby provoking audience to decide first to enter and second to turn male- or female-ward. In an exceptional interplay of form, structure and content Akers spaces Imponderabilia musically: Samples of 2010 MoMA reenactments are counterpointed by archival footage of the original performance and toward the end all merges as current-day Ulay is audience/participant to his own past. His expression as he sidles through the body-door is soft and sharp, intimate and stoic, close and abstract…this cross with self too multidimensional for translation into common tongue.

MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ THE ARTIST IS PRESENT: Marina Abramović. Photo Credit: David Smoler/ Courtesy of HBO Documentary Films & Music Box Films

More typically, the film treads familiar stylistic and formal terrain, sometimes pandering to mainstream expectations. One particularly suspect reality TV-like scene finds Abramović sick in bed while mounting her best effort to be well again in time to go on with the show. Yet she is ever-captivating: She talks about swallowing unscrupulously any and all antidotes brought by friends and about how the color red—in free flow around her—will return her strength. And as ever she is a striking appearance. I am torn here as a viewer between a raw desire to “be” with the artist in all capacities and a more critical sense that spaces of intimacy are easily endangered.

The sickbed scene evokes another elemental figure of performance art history: Linda Montano who wore red for a year as part of her 7 Years of Living Art (1984-91). I could have missed something, but apart from Ulay I do not recall any actual naming of other performance art pioneers in the multi-narrated course (including curators and historians) of Akers’ film. This elision is exactly what Abramović has become the exception to with her Guggenheim exhibition Seven Easy Pieces (2005) and the MoMA retrospective serving as both cause and consequence of her celebrity.

MoMA Multimedia (web resource) features audio of Abramović grounding Seven Easy Pieces in “an enormous amount of anger” she felt toward the entertainment and art marketplaces for blindly appropriating artists’ works. As a corrective she reenacted seminal body-art performances from the ’60s and ’70s, including her own as well as projects by Gina Pane, Joseph Beuys, and VALIE EXPORT. Seven Easy Pieces (2005) in the form of a video installation was part of the MoMA show and the film Seven Easy Pieces by Marina Abramović (2007) by Babette Mangolte is in distribution. Given Abramović’s precedence to historicize herself in relation to contemporaries (and not as a singular entity), the relative absence of such in the documentary (apart from her collaborations with Ulay) makes me wonder.

At the beginning of Abramović’s performance The Artist is Present Ulay sits across from her. She reaches for him, grasping hands. As with their original collaboration Night Sea Crossing—first performed in 1981 and prefiguring this solo project—he gets up and leaves (in NSC his body literally failing after days of fast and stasis), she remains seated. Akers’ film conveys Ulay’s profound belief in Abramović as an artist. Whatever demise their relationship suffered, he did not revise their history (their collaboration) into a weapon against her. The documentary makes clear too that Abramović became an invigorated subject of late Capitalism post-Ulay. Perhaps always art-business savvy—during the Q&A one person underscored how much still- and moving image documentation of Abramović’s body of work exists—her self-marketing abilities have certainly been accelerated by Sean Kelly (Gallerist/Dealer) and Biesenbach. It is with the curator that we leave her. Marina Abramović: The Artist Is Present concludes with the artist and Biesenbach face-to-face in the final throes of the performance (and the exhibition).

MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ THE ARTIST IS PRESENT: Marina Abramović. Photo Credit: David Smoler/ Courtesy of HBO Documentary Films & Music Box Films

The day of the Austin screening I had interviewed some young elite distance runners who spoke about their intimacy with pain. The film’s scene of a limping Abramović devotee (her leg asleep from so many hours of gazing) reminded me that my last direct experience of MoMA was following the 2011 NYC Marathon, the museum teeming with athletes barely able to move. Abramović’s asceticism (a word with Greek roots meaning “training” and “exercise”) trumps the day: Nobody competes with her ability to endure and to exist immaterially. In her own words, “the hardest thing is to do something that’s close to nothing.” All other than sitting and being is excess. Her frenetic will to action makes this state possible.

Marina Abramović: The Artist is Present

August 22, 2012, Austin

Presented by Austin Film Society at Alamo Drafthouse South Lamar

_______

Caroline Koebel is an Austin-based writer and filmmaker on faculty at Transart Institute (New York-Berlin). She has published in Jump Cut, Brooklyn Rail, Afterimage, …might be good, Art Papers, Wide Angle, and elsewhere. Her experimental films and art videos have played internationally, with recent retrospectives at Cine//B (Santiago, Chile) and Directors Lounge (Berlin, Germany). She holds a BA in Film Studies from UC Berkeley and an MFA in Visual Arts from UC San Diego.